An Informal Thatched Shelter

landscape, design, architect, parks, grounds, formal, roads, paths and aesthetic

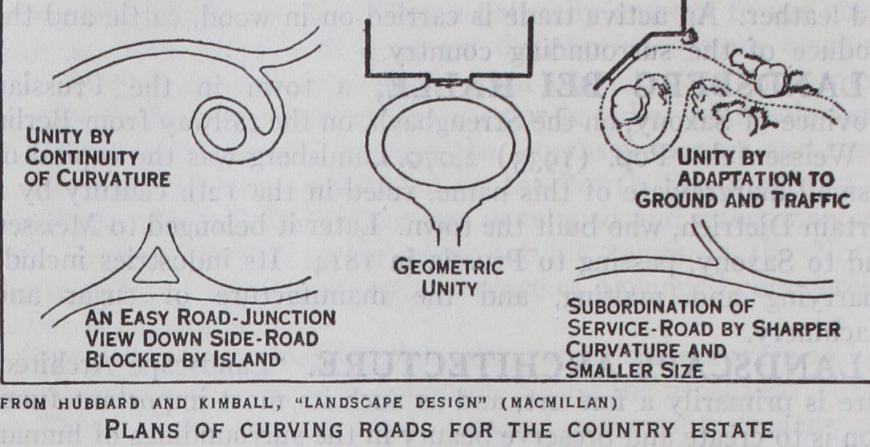

Roads and paths are differently handled by the designer accord ing as they form part of a humanized or a naturalistic compo sition. In formal landscape design, roads and paths are often important elements in the composition—as great approach avenues or as brick-paved walks among flower beds. In natural or naturalistic landscape, however, roads and paths are usually con veniences to be tolerated only as they reveal the beauties to be seen along their routes. The selection of their surface and the design of their form would be intended to make them as little conspicuous as possible. Road design in general must be care fully adjusted to topography, and sequence of curve carefully studied in relation to traffic. Views of and from roads and paths are important factors in the enjoyment of landscape designs. In informal landscape there is usually to be secured a series of pictures along the way itself and between groups of plantings off across the country-side. In formal designs, roads and paths may mark important axes, constituting the basic pattern of formal park or garden ; and, in any case, serving inevitably as boundaries between other units, their proportions must be carefully studied, as well as their colour and texture, in relation to other elements in the whole composition.

Practice.

In the actual designing of works of landscape archi tecture, purely aesthetic consideration such as those just consid ered are constantly being modified by economic aspects inherent in the proposed use of the land. These economic aspects are just as much part of the design as the aesthetic ; and on their recogni tion and skilful embodiment depends the success of the result as a physical organism to be used by man. In some problems— such as the small house on a city lot or a low-cost housing develop ment—economic considerations are paramount and leave to the designer little choice of the aesthetic form in which he shall express them ; in others—such as a great formal garden for a wealthy client—economic limitations are slight, and the designer can build his work of art more out of his imagination.

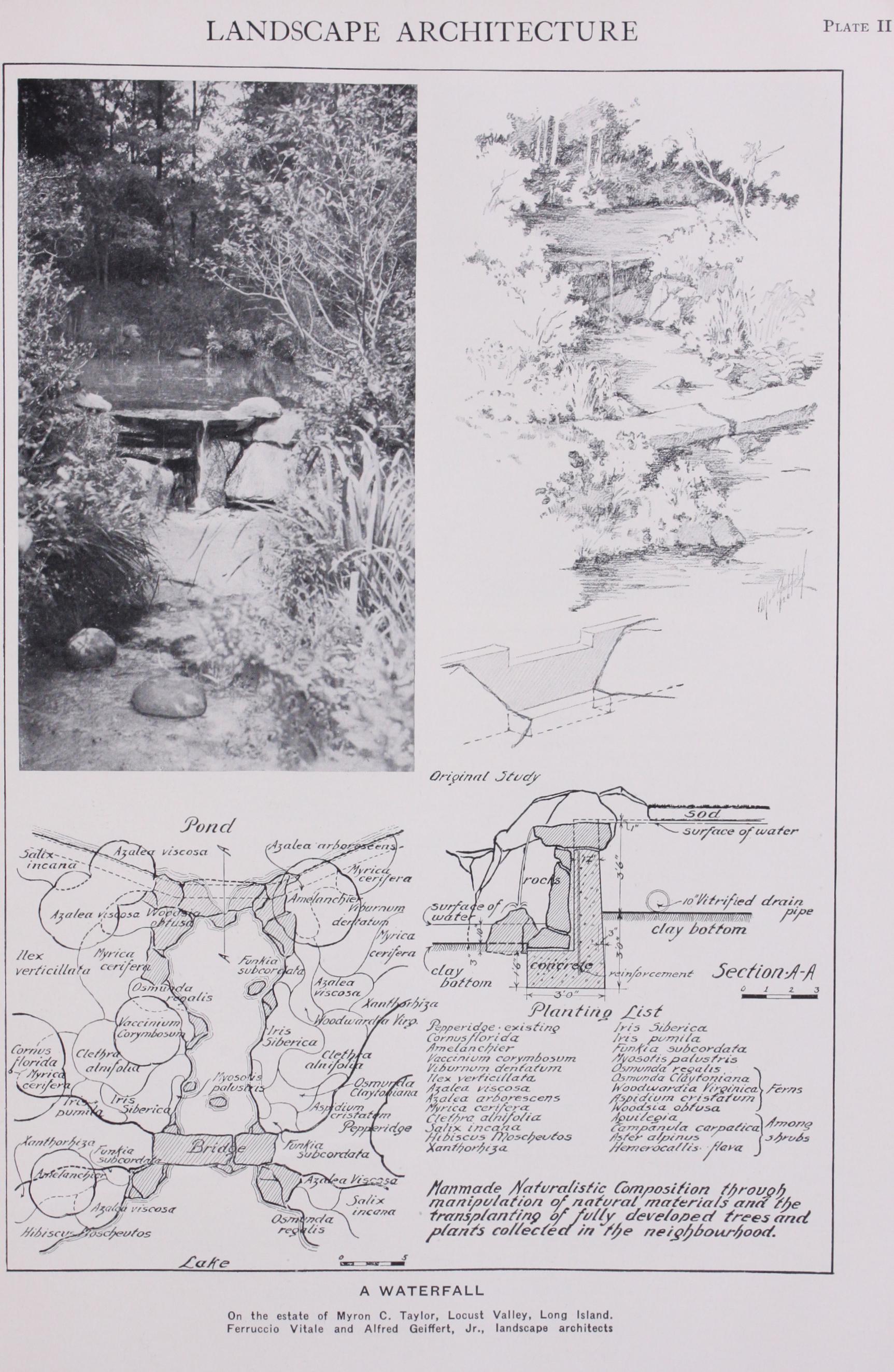

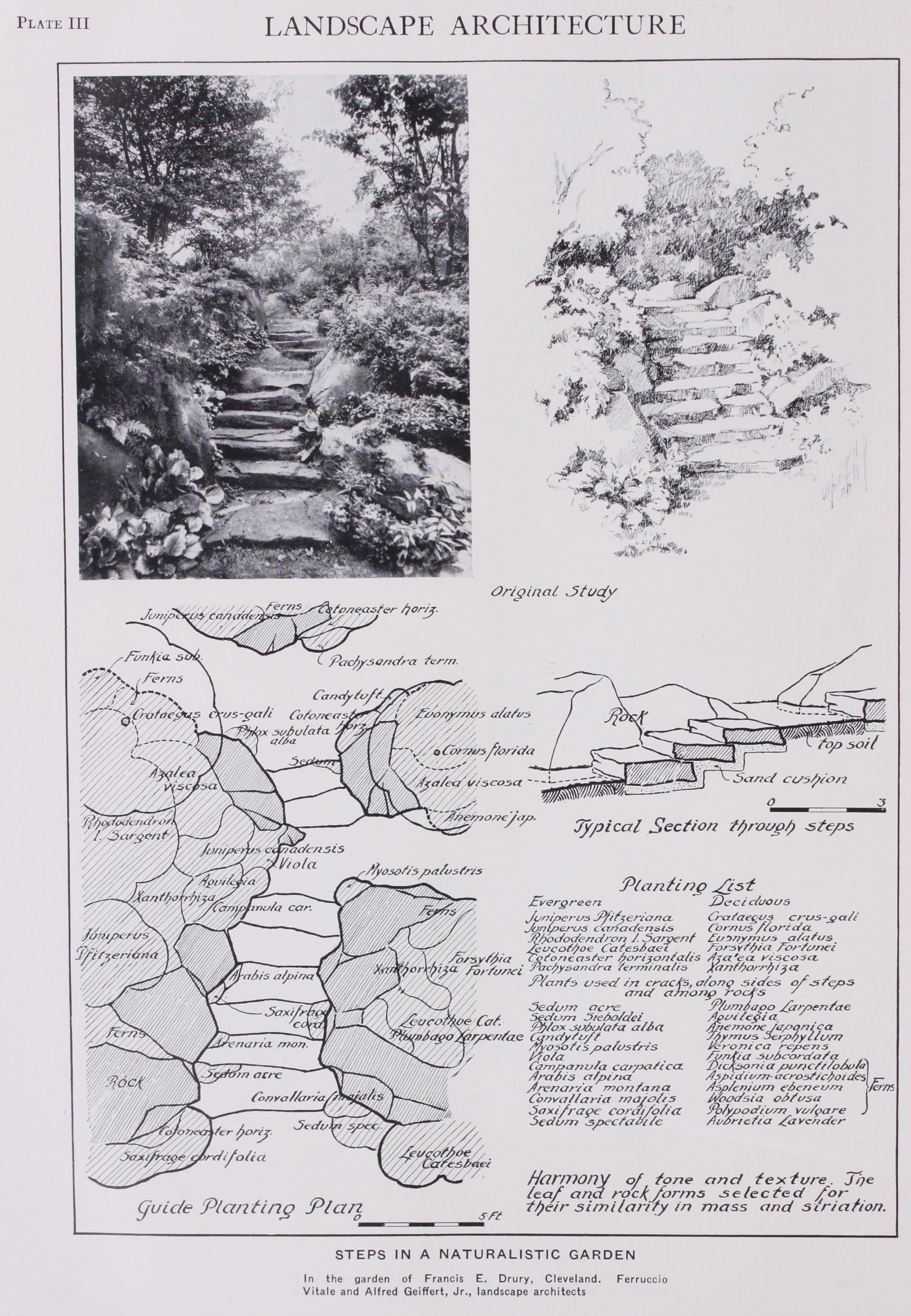

Having composed the aesthetic and economic elements required by the problem, and recorded his scheme either by drawings or, less often, by verbal explanations, the designer must proceed to put the design into execution. If he is experienced, most of the possible difficulties of construction will have presented them selves as limiting economic factors and will have been provided for in the design. Design and construction, in landscape archi tecture even more than in architecture, cannot be divorced, since on the knowledge of what can actually be built and grown depends the designer's ability to produce real rather than theoretical solu tions of the problems offered.

The relations of landscape architect to clients, contractors and collaborating practitioners are generally established in America, as well as the sequence of work on a given job, following from collection of topographic data and making of preliminary sketches, through representation of design in show plans and construction drawings, to superintendence on the ground of construction and maintenance.

The types of problems now within the field of landscape archi tecture in various parts of the world, developing from the smaller range of historic examples and from multifarious modern needs, comprise private estates, urban and rural ; country clubs, golf courses, hotels and camps; the grounds of hospitals and similar institutions, of universities, colleges and schools; the grounds of manufacturing plants and commercial establishments; railroad grounds ; the grounds of national, State and civic buildings ; ex positions ; fair grounds and amusement parks ; open-air concert and tea gardens, beer gardens and outdoor restaurants ; zoological parks, botanical gardens and arboretums ; cemeteries ; the whole range of outdoor recreation facilities—from great scenic or forest reservations and national or State parks through naturalistic or formal urban parks, large and small, to the provision for active sports in playgrounds, athletic fields, "sport parks" and grounds for the special sports, such as flying, racing, polo, bowling, tennis or winter sports ; and also to recreational waterfronts on sea, lake or river ; in addition, land subdivision and larger problems of city, regional and even State and national planning, including systems of parks and parkways, of motor highways for pleasure and commercial traffic, and "zoning" of land for appropriate use.

In many of these larger problems the landscape architect col laborates with other professional practitioners,—engineers, archi tects, economists, sociologists or lawyers. In domestic problems the collaboration of architect and landscape architect is common in America, although in some of the best formal work Charles A. Platt has combined these functions ; but in England and France architect, contractor and nurseryman frequently complete the estate without benefit of landscape architect.

Taking a general retrospective view, the problems which have most influenced the growth of the art and profession of landscape architecture are: the garden, because it offers the oldest and most numerous examples ; the park, because in it developed the con scious adaptation of landscape for public enjoyment ; the exposi tion, because from the Chicago World's Fair came a revival of the collaboration of artists; and in the past two decades, the land subdivision, because it has revealed fruitful opportunities in city building.