An Informal Thatched Shelter

nature, gardens, landscape, design, art, degree, kent, garden, trees and according

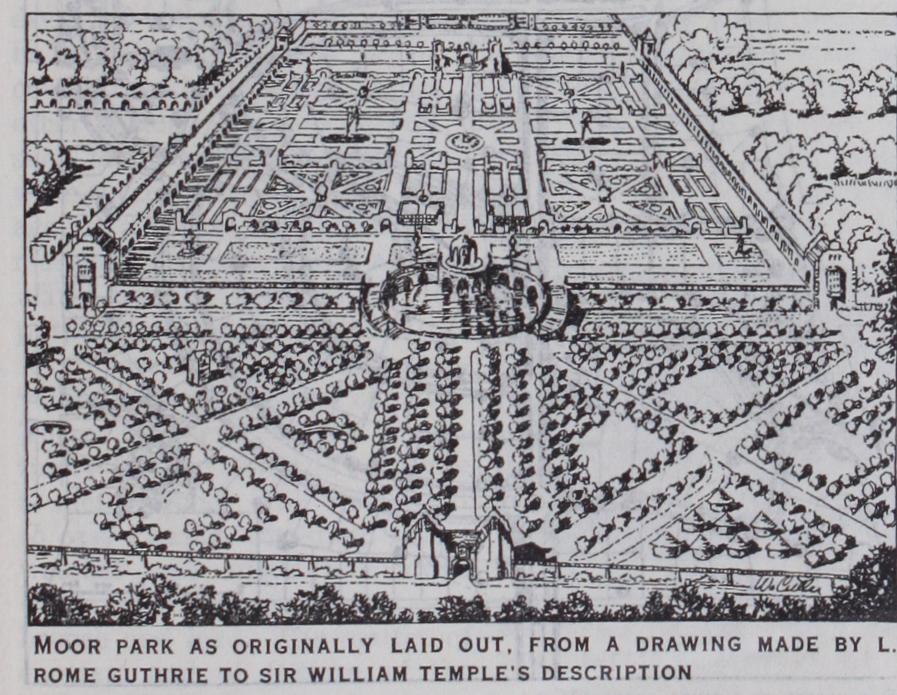

It must not be supposed that all who adhered to the then popu lar formal method of design were committed to its vagaries. Men such as Bridgman, who succeeded London and Wise in the favour of royal patronage (being gardeners to George I.), had the soul and sense of real design. He banished the clipped animals and monstrosities in yew, box and holly, and refused to be bound by the square precision or rules of the foregoing age. He refused to conform to the set symmetrical balance of one-half answering ex actly to the other, and although he still adhered to straight walks and clipped hedges, they were only his determining axial lines and he diversified the free open parts with groves of oak and native trees, and incorporated in his schemes pieces of the natural, if such were worthy to be included. In this way Bridgman antici pated the present day, when gardens are modelled upon long de termining axial lines, allowing the subsidiary walks to wander forth in easy routes as they fit in with the contours.

We may lay the blame for the change of the public taste upon the vagaries of topiary work, but change was inevitable. When ever men fall to imitating one another in art and hold solely by academic rules, their system is bound to run to seed. In garden design we must ever be refreshing ourselves by communion with nature in her broadest aspects on the mountain side, in the woods and fields, and any rules which we formulate must thereby be proved and attested. It was by this line of argument that Addison began the attack upon the formalists in the Spectator, and whether right or wrong this was his statement : "We may assume that works of nature rise in value according to their degree of resemblance to works of art. Therefore, works of art rise in value according to the degree of their resemblance to nature. Gardens, being works of art, therefore rise in value according to the degree of their re semblance to nature." Time has modified the crudeness of this argument, for we do not in general prize works of art or gardens according to the degree of their resemblance to nature; rather we deduce certain principles and conventions from nature, and pro duce a rhythmic pattern based upon them, modified to suit the scale of the district, the nature of the garden and the residence. Pattern and rhythm are the soul of design.

Pope and Horace Walpole, who wrote in the reign of Queen Anne, followed up the attack begun by Addison. Walpole's com plaint against the lack of ideas and imagination in the prevalent formalism may be judged from the following quotation: "At Lady Orford's in Dorsetshire, there was when my brother married, a double enclosure of 13 gardens, each I suppose not more than ooyd. square, with an enfilade of corresponding gates, and before you arrived at these you passed a narrow gut between the two stone terraces that rose above your head and which were crowned by a line of pyramidal yews." The Naturalists.—By this means the natural manner gained the day and became the rage, and for a time lost its head, perpe trating as many extravagances as the school it had replaced. Rev olutionaries are always extremists and we may smile at Pope turn ing his five acres at Twickenham into a compendium of nature, condensing every kind of scenery into his villa garden. Into this ferment of rebellion against the old garden usages entered Wil liam Kent, architect and painter, fresh from a period of study in Rome, his mind steeped with the heroic landscape compositions of Claude and Poussin, which it was his intention to visualize materi ally, using the country as his can vas, and the trees, the water and the rocks as his paints. Such a

propaganda was foredoomed to failure ; nature will not be rushed out of her country and clime. Yet Kent, under the patronage of Lord Burlington and with the eulogies of Walpole and others be hind him, was deemed a genius. In spite of his rich patrons and advocates, Kent was not the man to lead the movement; he had no feeling for pure landscape for its own sake. He was a creditable architect and furniture designer and in his gardens he always harked back to his bent by inserting Greek and classic temples.

After Kent came Launcelot, or as he was nicknamed, "Capabil ity" Brown, a man who has been much derided; yet, judging from the work he did at Blenheim and from the survivals of his vast planting schemes, composed mostly of oak or one kind of tree he had a true eye for landscape composition. He ran the con tours of the landscape right up to the mansion, with no apparent break. In order to keep the deer and cattle from approaching the mansion he made use of the ha-ha fence which made the grass appear to be of one uninterrupted sweep. His was the erroneous motto, "Nature abhors a straight line," therefore even when the ground was flat and the logical thing to do was to lay it down to a level lawn, he undulated it. Again, when a level plain invited a straight drive through an avenue, he made it wind about, and girded it with clumps of trees. Although he was somewhat hemmed in with his own maxims and mannerisms, his work marked a dis tinct advance, as did the work of his successor, Humphrey Rep ton, who is justly celebrated as a champion of the landscape style. In his way Repton was an idealist, a fact which is proved by his "Red Books." For each place of importance he prepared a report, bound in a red cover, and a series of sketches showing the result when the trees had attained a certain maturity, so that although his effects were not as demonstrable as geometrical gardens, which can be projected in planes by perspective drawing, there was a degree of probability in his proposals. Although Repton professed to be a follower of Brown, he was far ahead of his master in in telligent grasp of what constitutes design. In many instances he refused to destroy worthy old gardens and in others he readjusted the vagaries of his predecessors. He knew what was consistent with the various styles of architecture and recommended mostly a broad expansive formal scheme near the house, merging into the natural, attaching the house by imperceptible gradations to the landscape. He never lost sight of the house as the dominating factor, and in his domestic schemes everything worked from it and ministered to its elegance and comfort. He was a fairly pro lific writer, and became the champion of the landscape school, maintaining a long argument in print with Sir Uvedale Price on its behalf. Other writers such as Burke, in his Essay on Taste, dealt with the philosophic aspect of beauty. Then there were long poetic effusions by William Mason and Richard Knight. The former published between 1772 and 1782 four consecutive books of poetry which were often reprinted.