Lighthouse Structures

light, lens, lenses, reflectors, fig, glass, fresnel, dioptric and annular

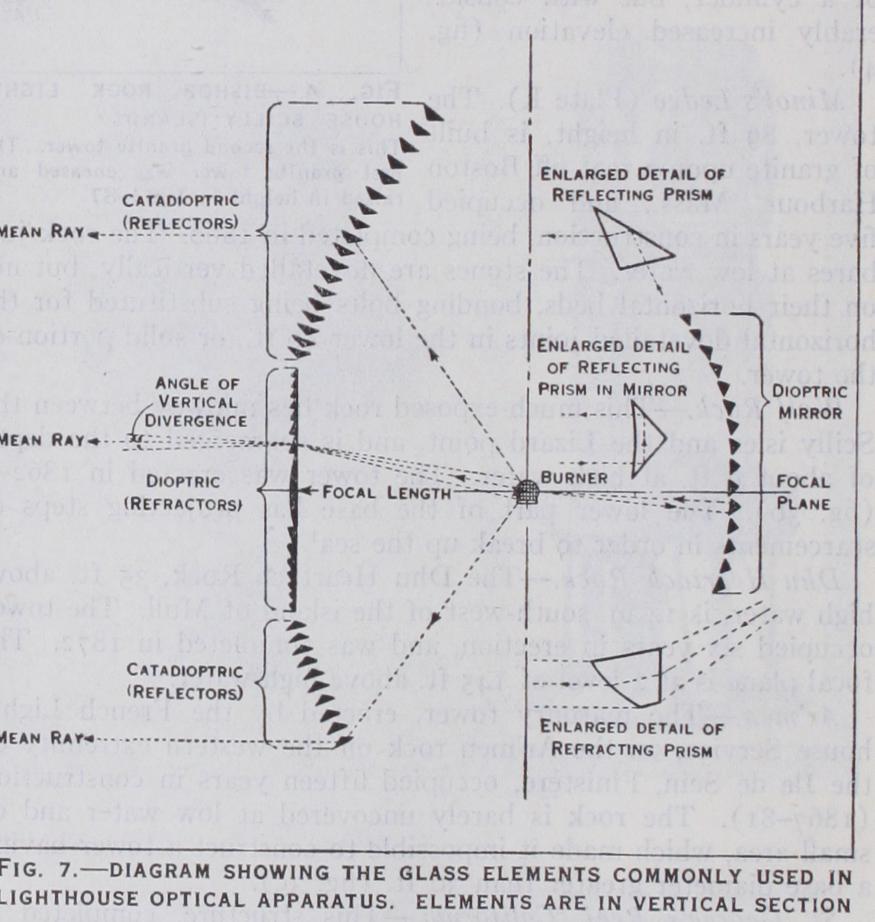

Three types of apparatus are used to effect these concentrations: (a) Catoptric in which the rays undergo reflection only at the surface of a mirror; (b) Dioptric in which the rays pass through a glass medium and are bent or refracted as they enter and emerge from it (fig. 8) ; and (c) Catadioptric in which the rays after entering the glass medium suffer total internal reflection be fore emerging from it (fig. 7). The object of these several forms of optical apparatus is not only to produce characteristics or distinctions in lights to enable them to be recognized readily by mariners, but to utilize the light rays to the best advantage by their condensation. This is accomplished more effectively by the use of revolving annular lenses than by fixed belts, as greater intensities are thereby attained. Fig. 7 shows in diagrammatic form the various sections and dispositions of glass elements com monly used in lighthouse optical apparatus.

Catoptric System.

Paraboloidal reflectors, consisting of small facets of silvered glass set in plaster of Paris, were first used about the year 1763 in some of the Mersey lights by William Hutchinson, who was then dock master at Liverpool. Spheroidal metallic reflectors were introduced in France in 1781, followed by paraboloidal reflectors of silvered copper in 1790 in England and France, and in Scotland in 1803. The earlier lights were of the fixed type, a number of reflectors being arranged on a frame or stand in such a manner that the emergent rays overlapped and thus illuminated the whole horizon continuously. In 1783 the first revolving light was erected at Marstrand in Sweden. Similar apparatus were installed at Cordouan (1790), Flamborough Head (18°6) and at the Bell rock (I8I I). To produce a revolving or flashing light the reflectors were fixed on a rotating carriage hav ing several faces. A type of paraboloidal reflector is still used for light-vessel illumination.

About the year 190o reflecting mirrors were used in the Heligo land lighthouse in combination with electric-arc lamps. The French lighthouse service installed a quadruple-flashing light at Galite in Tunisia, which has large gilded and burnished paraboloi dal reflectors and incandescent oil burners. It is, however, unlikely that such reflectors will take the place of dioptric lenses. Para boloidal reflectors have also been used in some aerial lighthouses including that at Mount Valerien, near Paris.

Dioptric System.

The first adaptation of dioptric lenses to lighthouses is probably due to T. Rogers, who used lenses at one of the Portland lighthouses between 1786 and 179o. Count Buffon had in 1748 proposed to grind out of a solid piece of glass a lens in steps or concentric zones, in order to reduce the thick ness to a minimum (fig. 8a). Condorcet in 1773 and Sir D.Brewster in 1811 designed built-up lenses consisting of stepped annular rings. Neither of these designs, however, was intended to apply to lighthouse illumination. In 1822 Augustin Fresnel constructed a built-up annular lens in which the centres of curva ture of the different rings receded from the axis according to their distances from the centre, so as practically to eliminate spherical aberration ; the only spherical surface being the small central part or "bull's eye" (fig. 8). These lenses were intended for revolving lights only. Fresnel next produced his cylindric refractor or lens belt, consisting of a zone of glass generated by the revolution round a vertical axis of a medial section of the annular lens (fig. 8). The lens belt condenses and parallelizes the light rays in the vertical plane only, while the annular lens does so in both planes. The first revolving light constructed from Fresnel's designs was erected at the Cordouan lighthouse in 1823. It consisted of 8 panels of annular lenses of 45° verti cal aperture and having a focal distance of 92o mm. To utilize the light, which would otherwise escape above the lenses, Fresnel introduced a series of eight plain silvered mirrors, on which the light was thrown by a system of lenses. At a subsequent period mirrors were also placed in the lower part of the optic. The apparatus was mounted on rollers and revolved by clockwork. This optic embodied the first combination of dioptric and catop tric elements in one design (fig. 9). Fresnel also designed for the Chassiron lighthouse a dioptric lens with catoptric mirrors for giving a fixed light, which was the first of its kind installed (1827) in a lighthouse. This combination is geometrically per fect, but not practically so, on account of the great loss of light by metallic reflection; this is 25% greater than that resulting from the use of glass elements. Shortly before his death in 1827 Fresnel devised his totally reflecting or catadioptric prisms (fig.

7) to take the place of the silvered reflectors previously used above and below the lens elements. In these the principle of in ternal reflection from the face of a glass prism is made use of as well as the principle of refraction. Thus a ray of light falling on the prismoidal ring is refracted as shown in the en larged detail of the reflecting prism and then is totally re flected emerging after a sec ond refraction in a horizontal direction. Fresnel devised these prisms for use in fixed-light ap paratus, but the principle was applied to flashing lights by T. Stevenson in 185o. Both the di optric lens and catadioptric prism invented by Fresnel are still in general use, the mathematical calculations of the great French designer still forming the basis upon which lighthouse opticians work.