Lumbering

lumber, logs, log, ft, tree, ground, logging, cuft, methods and forest

The estimated depletion of timber is estimated by the U.S. Forest Service as 13,463,000,000 cu.ft., the year 1936 being quoted as a typical year. Of this total, the timber cut for commodities was 11,400,000,000 cu.ft., of which 6,610,000,00o cu.ft. were softwoods and 4,790,000,000 cu.ft., hardwoods. Of the total, 5,367,500,00o cu.ft. is lumber; 3,620,000,000 fuelwood; 705,924,000 pulpwood; 681,250,000 hewed ties and fence posts. Fire and other destruc tive agencies, as insects and disease, account for loss of about 2,000,000,000 cu.ft. a year, about 7o% of which is softwood. The present stand, plus growth, less depletion and losses may be said to give an indication of the life of the lumber industry. But a rapidly increasing interest in reforestation and practice in timber management have been developing and the growth factor has been changed by increased productivity of forest crops and the growth and drain equation has been approximating a balance. With vigilance in preventing forest fires and depreciation and losses from insects and other natural causes, the lumber industry has a long life in prospect.

In the early days of American history and also the history of the American lumber industry, the manufacture of lumber was a comparatively simple and inexpensive and likewise crude process. The trees were felled as needed, hand sawed and shaped into rough planks and timbers by manual labour for nearby immediate use. Later on, as the country developed, a greater demand for lumber resulted and more efficient lumbering methods were needed and were created. Furthermore, as population and industry expanded westward, the forests moved farther and farther away from the centres of consumption, and each new lumber district presented somewhat different problems in logging, manufacture and distri bution due to topography and species of wood f ound—all of which had a marked influence upon the development of modern lumber ing methods.

Logging.

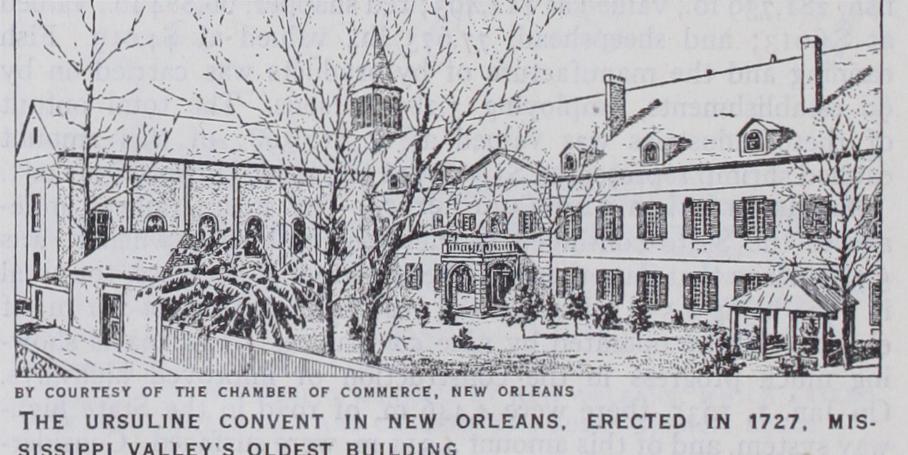

The work in the forest preparatory to that of the sawmill, logging, has been one of the most interesting features of the American lumber industry. In the early days and until recent years in many localities, the lumbermen depended almost wholly upon natural forces in the logging operations. In the North-eastern and Northern States the fall and winter seasons were devoted to the felling of the trees. The logs were hauled out on snow sleds, either to sawmills close by or to concentration points on the banks of streams, where, in the latter case, the logs were rolled into the water as soon as the ice was gone, and floated down stream to mills or market centres. In the South the lumbermen had to resort to other means of transporting the logs from the forests to the mills, due to a lack of swift flowing streams and snow for sledding. Oxen and high-wheel carts were the principal means of log transportation for years and in some districts in the South-east they still are used. In the moun tainous country, both in the East and West, chutes and flumes were used. Later came the use of wire cables stretched across val leys and canyons. The logs were hung from a pulley; then, by gravity, travelled to the lower end of the cable. Although these relatively primitive methods of transportation are still used in hauling logs from places where they are cut to the "log landing," in some areas they have been supplanted by tractors. At the "landing," they are loaded on trucks or railroad cars for transpor tation to the mill. Many of the larger companies have built their own railroads or truck roads long distances from the woods to the sawmill. There are approximately 30,000 mi. of logging railroads in the United States and probably an even greater mileage of truck roads. The development of truck hauling of logs has made accessible large areas of timber which had not previously been practicable to reach and has extended the life of many mills for years after the expiration of the expected cutting period. The earlylogging camps were very crudely built. They consisted of as few buildings as possible. The logging men or "lumberjacks" lived in rough shacks or bunk houses. Conditions were unsanitary and even as late as the zoth century many logging camps were more primitive than the first communities in Massachusetts and Vir ginia. Recreation consisted of "swapping" stories, fighting and drinking. Only at the end of the season did the lumberjack have an opportunity to mingle with civilization in some town a hundred or more miles away. But conditions changed. There are fewer lumber camps and more lumber towns. The average lumber jack can raise a family as well in the forest as he can in the city because he has, right at hand, schools, churches, stores, modern sanitary conditions and amusements.

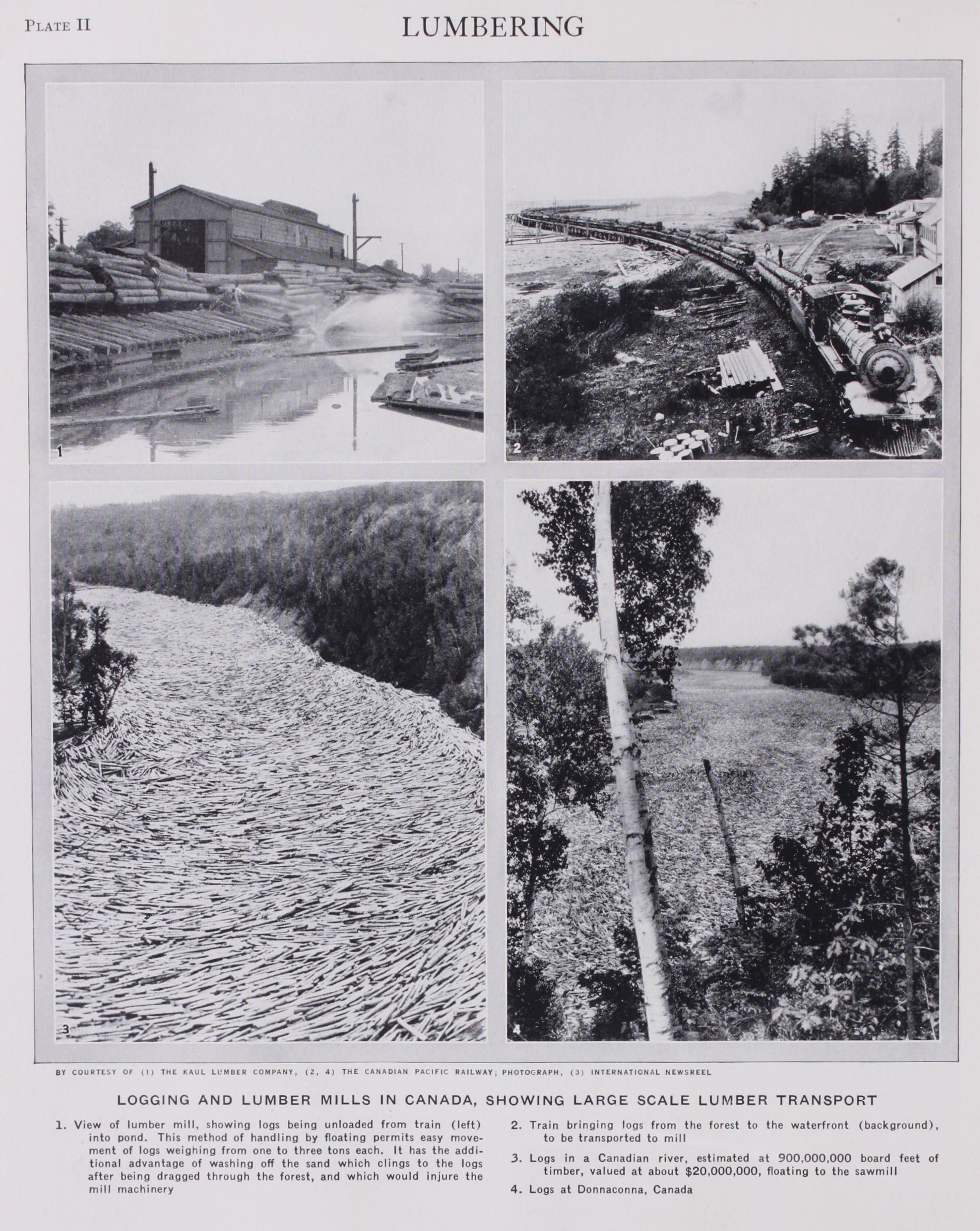

The methods of felling trees and converting them into logs are generally the same. First, the standing tree is undercut with an axe on the side of fall. A cross-cut saw, handled by two men—one at each end—is employed opposite the undercut. Where the ground is flat, the men cut from the ground but where the ground is rough or sloping and irregular, and particularly on the west coast, the undercutting and sawing is done from a platform or spring-board. After felling, branches are trimmed off and the tree is sawed or "bucked" into log lengths, usually 16 ft. except in the North west, where much longer lengths are handled (24 to 4o ft. are common and in the most modern operations 49 to 65 ft. are the most favoured units of length). Certain other districts also cut logs to lengths greater than 16 ft. After bucking, the logs are dragged or "skidded" to concen tration points by horses, oxen or power, but as previously ex plained, steam or electric power has supplanted, in many instances, the horses and oxen. Where steel cables are employed over valleys and canyons, the method is called "high-lead" skidding. Other methods are known as overhead skidding—where the logs are hoisted up over the brush and ground for some dis tance, and ground-line skidding which is the dragging of the log over the ground by means of a cable. In the North-west a "spar" tree frequently is employed in the skidding operations. This tree is selected for its height and favourable location with regard to the surrounding trees to be felled. A man known as a "high-climber," ascends the tree, aided by climbing spurs affixed to his shoes and a rope around the tree. He is equipped with a saw and axe and as he ascends he cuts off interfering branches until he reaches the desired height which usually is about 175 to zoo ft., and some 3o to 5o ft. from the tree top. Then he saws off the top, waits until the swaying caused by the top's rebound has stopped, and descends. Another man, known as a "rigger," next ascends, carrying equipment for rigging. Finally the spar is rigged at the top with cable and pulleys and a loading boom is affixed some 20 ft. above the ground. A cable with grab hooks on the end is carried to the log to be skidded and then, by means of a steam or electric skidder the log is dragged within distance of the loading boom which raises the log off the ground and loads it direct onto a nearby car or stacks it for future loading. When the logs reach the mill centres, they are stored in log ponds which usually cover a number of acres. Here they are kept until ready for manufacture. The ponds facilitate assorting and cleaning, and also prevent deterioration which would occur if the logs were left dry for any appreciable length of time.