Classes of Structural Members

beam, weight, fig, reactions, equal, load, loads, reaction and pounds

Whenever a piece of material is shortened or Lingthened, it is stressed. From Fig. 35 it will be seen that the material in the beam is stressed at the outer edges, and is not stressed at the cen ter of the beam. It is also evident that at any point between the middle and the edges, the ma terial is lengthened or shortened somewhat. This shows that the material is stressed at that point, but the stress is greater the nearer the point is to the outer edge. The distortion (that is, the shortening or the lengthening) at any point—and therefore the stress—is directly pro portional to the distance of the point from the center. At one-half the distance out from the center, the amount would be one-half of what it was at the extreme edge (see Fig. 35). At all points on the line the stress is zero; that is, there is no stress. For this reason the axis in dicated by this line is called the neutral axis of the beam.

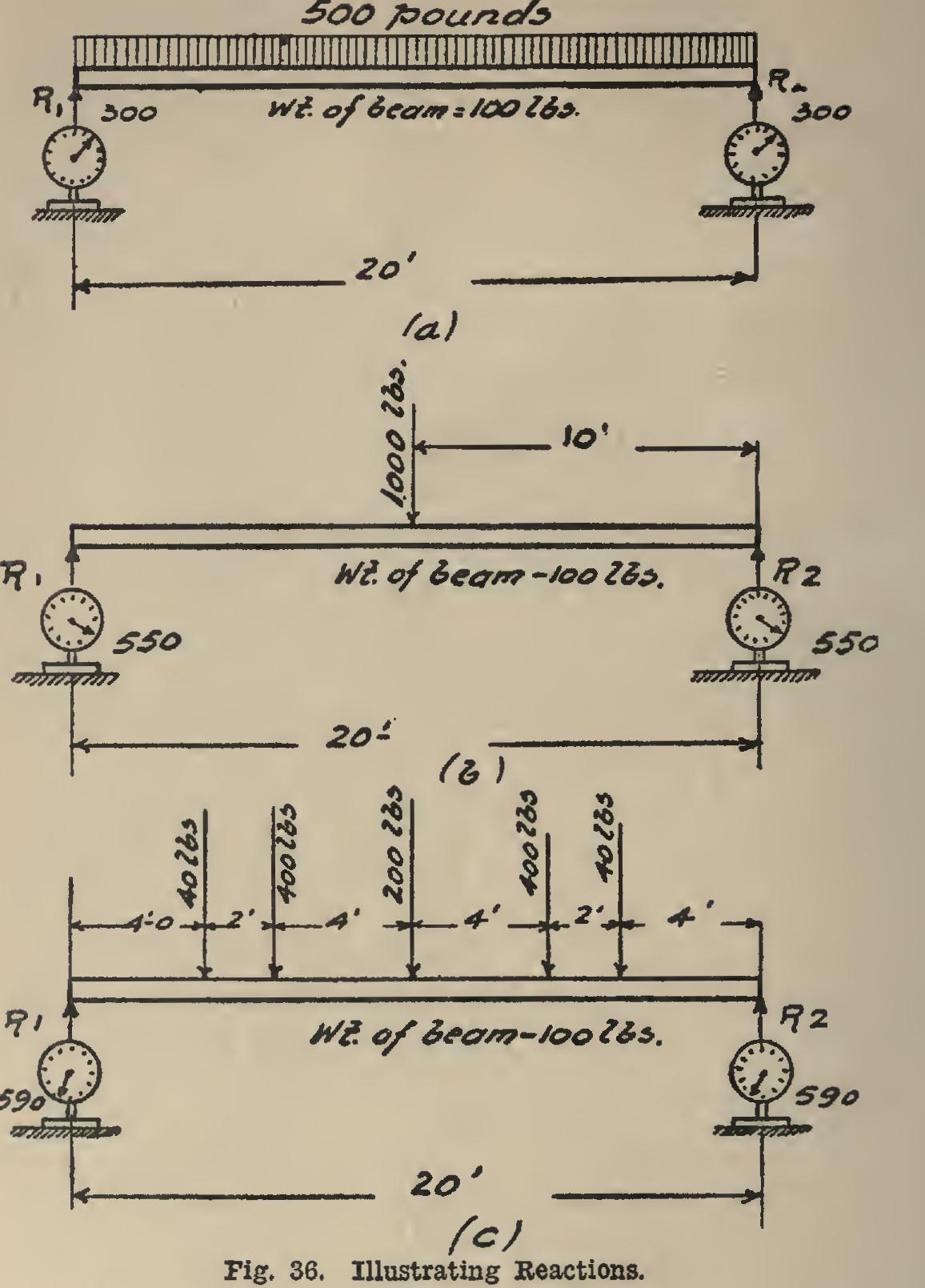

35. Reactions of Beams. If a beam had any load placed upon it, the ends of the beam having been previously rested upon scales, the scales would register certain amounts. If the amounts each scale registered were added together, they would give a total equal to the weight of the beam and the load upon it. The amounts regis tered by each scale are called the reactions; that is, the reaction is indicated by the amount of pressure that the beam exerts upon the sup port. As the pressure of the beam under its loads is downward, the reactions must always act upwards, in order to keep the beam in place. It is just the same—to take a simple example— as if one leaned over and pushed against a man; the man must push back if he expects to keep the first fellow in place. It is a fundamental proposition or truth, that the sum of reactions is always equal to the weight of beam and its loads.

If the load is a uniform one, if the load is at the center, or if loads of equal weight are placed at equal distances on opposite sides of the center, then the reactions will be equal, and each one will be equal to one-half the weight of the beam and the loads on it. The reaction at the left hand is usually called R„ while that at the right is called R., (see Fig. 36). For example, if the beam weighed 100 pounds, and the loads were distributed as in Fig. 36 (a, b, and c), the reac tions would be as follows: In Fig. 36 (a), of (500+100)=300 pounds; and would be the same.

In Fig. 36 (b), R,=one-half of (1,000+100)=550 pounds ; and R, would be the same.

In Fig. 36 (c), R,=one-half of (40+400+200+400+40+ 100)=590 pounds; and would be the same.

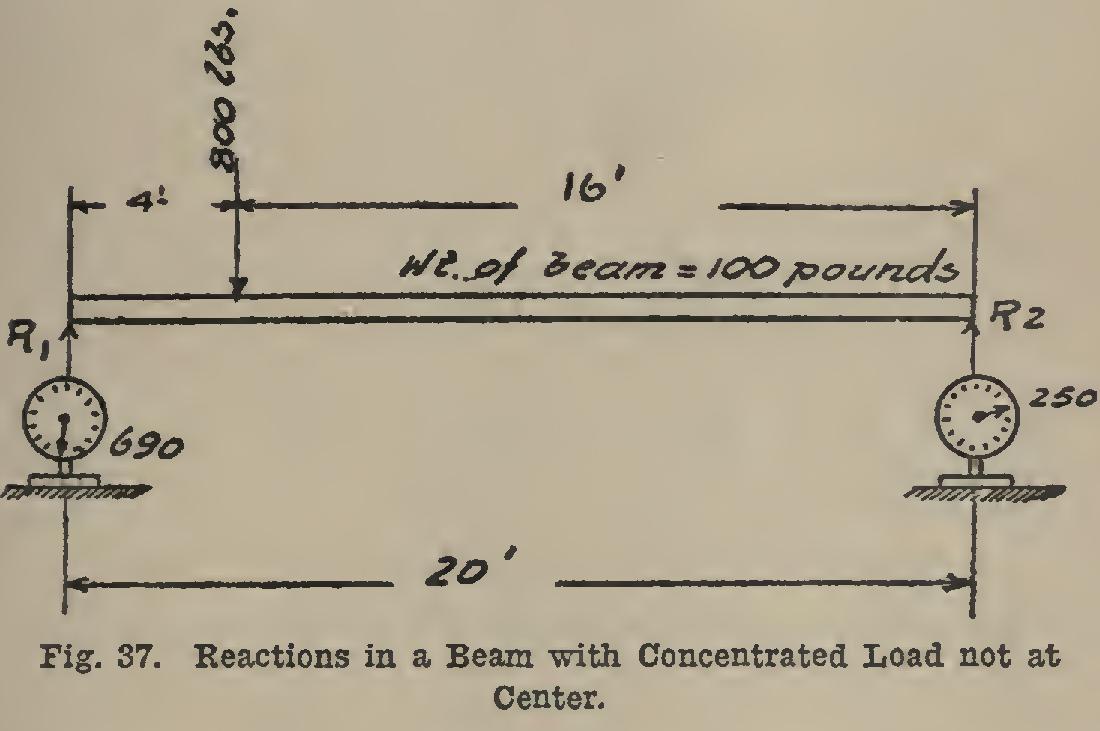

If the loads are placed differently from the above, the reactions will not be the same. If one load is used, the reaction nearest to the load will be greatest; and the nearer the load is to the reaction, the greater will be the reaction. If

the load is right at the support, the reaction will equal the load, together with one-half the weight of the beam. If the conditions were as in Fig. 37, the scales would register: As the total weight is 800+100=900 pounds (the 100 pounds being the weight of the beam), this must be equal to the sum of the reactions, and is so, as shown.

The determination of the reactions can be made without the use of scales. The reactions can be computed. In cases like those in Fig 36, each reaction is, as before stated, equal to one half of the load and the weight of the beam.

In cases like Fig. 37, or where there are more than one load irregularly placed or irregular in weight (Fig. 38, a and b), the determination is made as follows: Multiply each load by its dis tance from the end of the beam at which the re action is not desired, and divide this by the span of the beam. This will give the reaction due to the loads, and to it must be added one-half the weight of the beam. The result is the reaction.

For example, take Fig. 38 The compu tations are as follows: Therefore due to loads=374 25/30; and due to loads=345 5/30. Now, one-half the weight of the beam is 100-+-2=50 pounds; there fore, This 820 pounds is equal to the sum of the weights of all the loads and the beam.

When the sum of the computed reactions is not equal to the sum of all the weights which produce them, it is evident that an error has been made in computing them, and the work should be done again.

In Fig. 38 (b) the loads are placed sym metrically with respect to the center; but they are not equal in weight. The reaction is computed as follows: is 725 5/30, and this should be worked out by the reader.

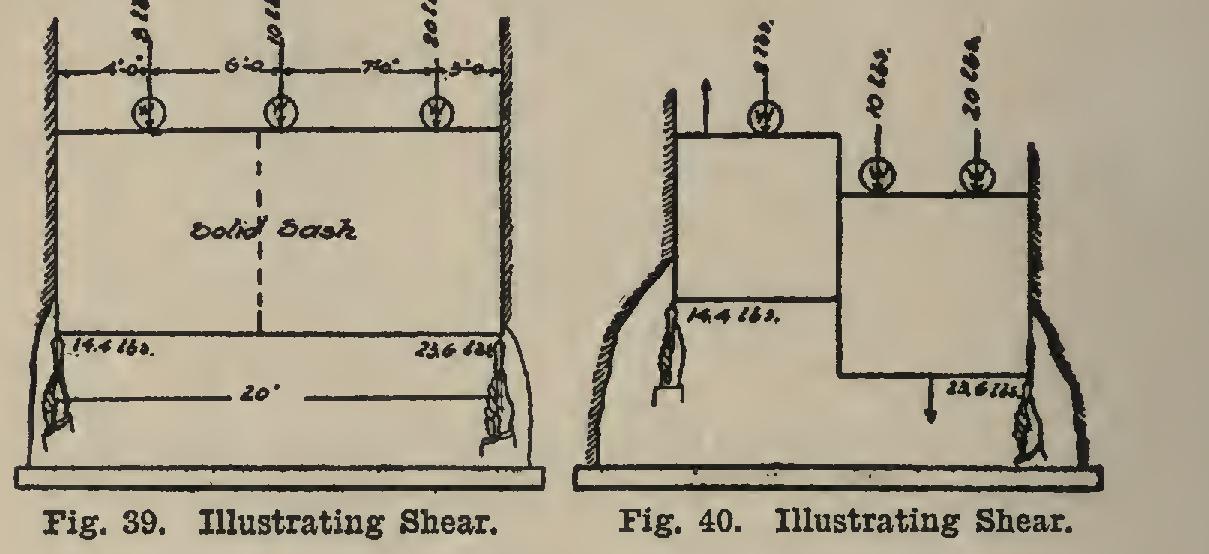

36. Shear in Beams. Suppose that in place of the window-sash a solid piece were put in, and that the sash weights were taken off and cer tain weights placed on the top. Also, in order to keep the sash from going clear down, supports were placed under the ends, Fig. 39, and pressed upward with pressures of 14.4 and 23.6 pounds. This piece is then in reality a beam; and the pieces of wood which support its ends are in reality pushing upward with a force equal to reactions the reactions and The reactions due to the loads are and The weight of the beam is neglected in this case, as it is small. In all cases in this and the next ar ticle, the weight of the beam will be neglected, since, in the design of beams, the beam is not known until after the design is made, and there fore the beam is designed to hold up the loads upon it, then the weight of this beam is com puted, and then the beam is re-designed in order that it may carry both the weight of the loads and also its own weight. This method of pro cedure will appear clearer after it has been studied in Article 38.