English Systems of Floor Construction

floors, time, fire, terra-cotta, heat, concrete and porous

ENGLISH SYSTEMS OF FLOOR CONSTRUCTION In this connection, some valuable informa tion will be found in the following account of methods of floor construction employed in England: Within the last twenty years, a very great number and variety of fire-resisting floors have been adopted and patented in England. Some have died a natural death for want of fitness for the object in view; others have been kept alive by means of advertising and persistent push, irrespective of merit. In the course of time mat ters will adjust themselves, and Darwin's theory of the survival of the fittest probably applies to concrete construction as well as to the develop ment of living species. It must not be assumed that the floors illustrated are suggestive of the best. They are intended only to show the prog ress and changes made in the methods of con struction, the materials employed for the pur pose, and typical examples of those more gener ally known and in use at present.

The opinion at one time was that if the ma terials of which floors and other parts of build ings were made were incombustible, they were fireproof; their behavior when simultaneously exposed to intense heat from the under side and the application of streams of water playing on the upper side, were not taken into account. It has nearly always been the case that the bottom flanges of iron and steel beams have been quite exposed, or at most covered with a thin coat of plaster. As the iron joists must, in a large fire, under these conditions, attain a high tempera ture in a short time, the heavy weight would cause them to bend; and the lower half of the concrete floor, already weakened by heat, would, as a result, be subject to an increased tensile strain. The heat would render the bottom flanges weak at the time when the strain upon them was greatest; and a general collapse was often the result, causing fireproof floors in their early days to be avoided in buildings on fire. Another cause would be the expansion and sub sequent contraction of the concrete mass; for, if the floor was in inseparable sections, each of many superficial feet, it would probably part at its weakest places through the heat causing it first to expand and then contract as it cooled.

What it amounts to is that to render fire resisting floors as much so as possible, every por tion of steel or other metal construction should be encased in or covered with some material which both resists heat without breaking up, as far as practicable, and is also a bad conductor.

Fire clay or pottery clay will effect the pur pose to a great extent if some way is adopted to afford means of expansion and contraction.

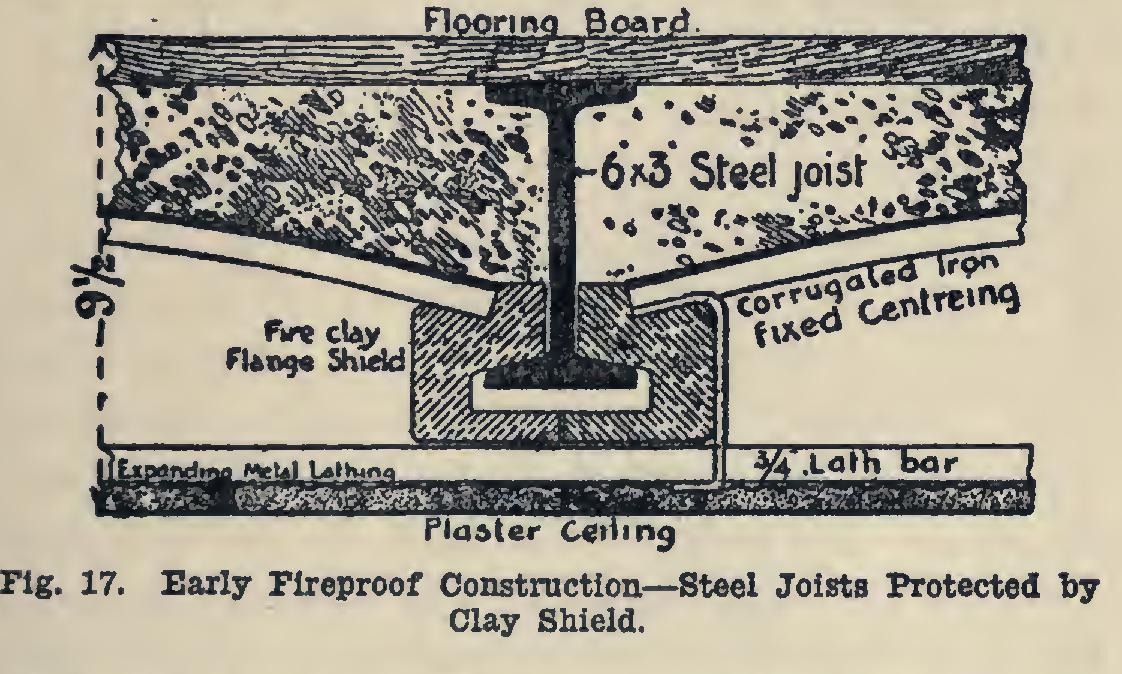

With this view, shields for steel joists about 12 inches in length, made of pottery clay, either in two pieces as shown in Fig. 17, or in one piece, have been used. In the latter case they have to be put on the joists before the latter are fixed, for both floors, arches, or slabs and for column or girder coverings.

Another writer says: "For certain purposes the porous terra-cotta lintel may be useful and economical; but, generally speaking, concrete is found to be more practical and constructionally more sound, and, all things considered, less costly. As for dense terra-cotta for floor con struction, or the protection of metal work, its application is scientifically and practically wrong; in fact, terra-cotta is distinctly danger ous from the fire point of view. The complete disappearance of dense terra-cotta in floors and protective coverings intended to be fire-resist ing, is only a matter of time." The expressions "porous" terra-cotta and "dense" terra-cotta are intended to apply, the latter to material as used for building purposes in the ordinary way, while the "porous" terra cotta consists of common fire clay, in which saw dust, shavings, charcoal, tree bark, or other combustible materials in a fragmentary state, are mixed, and which, being consumed at the time the blocks are being burnt in the kilns, ren ders them porous. The practice was known in this country [England] many years ago, and it is said was introduced to enable nails to be driven for the fixing of joinery or timber work.