Polygons and Miters

shown, lines, line, square, figures, degree and tongues

These fractional numbers are to the 1-24 part of an inch and are about as near as can be had on the steel square, none of them varying over .02 of an inch. Polygons are known by the number of their sides as per the above names. given in their order up to the twelve sided figures, after that, with the exception of fifteen which is called quindecagon, are known as polygons of so many sides.

In some of the encyclopedias the triangle and square are not classed with the polygons, but we see no reason why they should not be, since the rule that applies to other sided figures applies to them also.

The subject of polygons is not as well under stood as it should be. It is quite a common thing to call most any kind of a corner aside from the right angle, an octagon corner, due no doubt to the fact of their little demand in practical work, for, aside from the octagon, they are but little used. However, it is well to know them, and to know one is to know them all.

Though many of the illustrations that we have given may never come up in actual practice, they show that when the principles are once undersdood the mechanic will know how to proceed to apply the square to solve anything pertaining to angles in his line of work. However, we have a few more illustrations that we wish to present before passing them by.

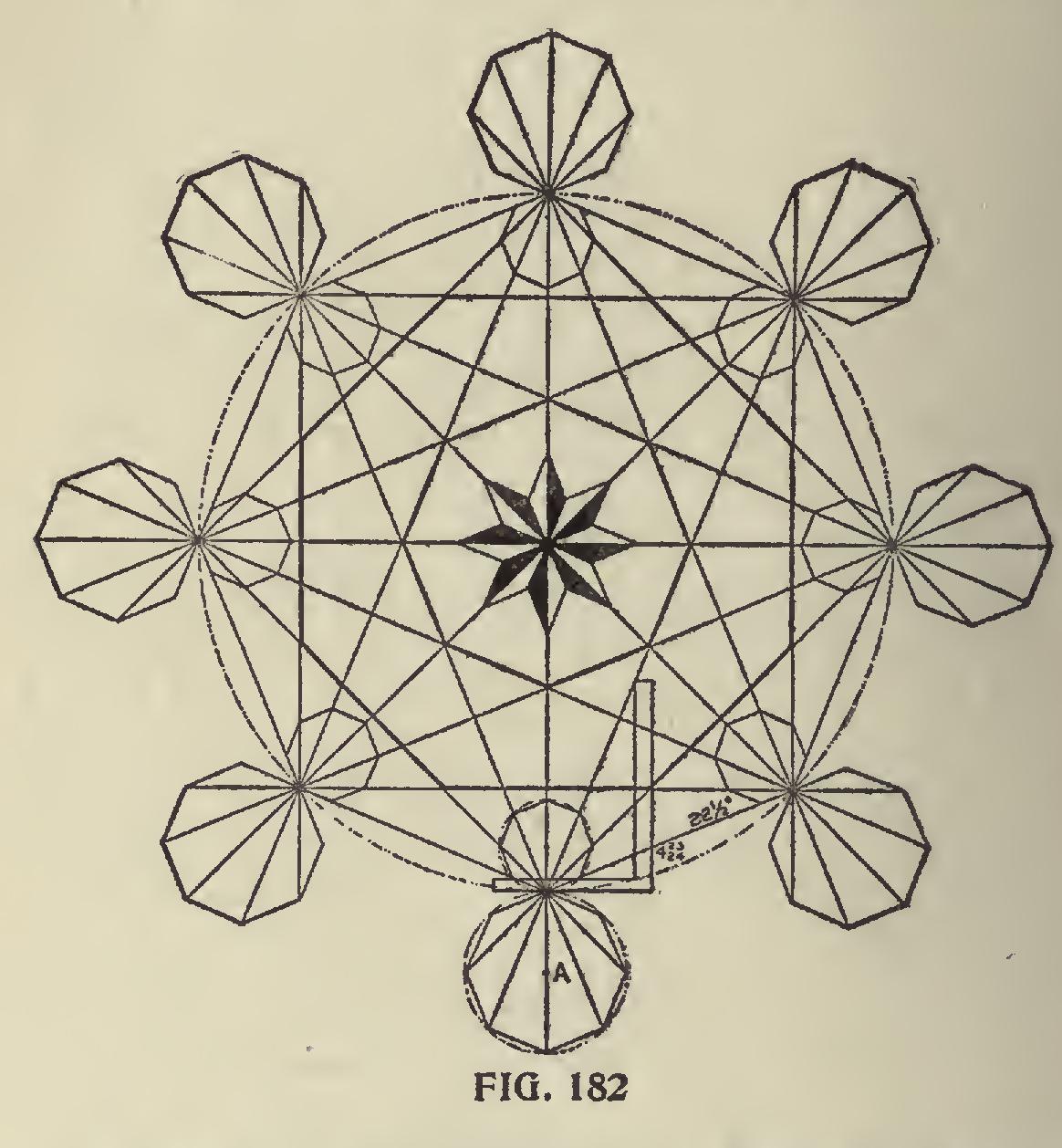

In Fig. 182 is shown an example in line work.

The figures to use on square are those for the oc tagon miter and consequently the whole figure runs to the octagon. The eight lines radiating from 12 on the tongue are 22i degrees apart, the first one intersecting the blade at 4.97, or practically 4 23-24 inches. The center for this design according to size wanted can be taken at any desired point on the 90-degree or perpen dicular line above 12 on the tongue, and where the circle cuts the first degree line from the tongue determines the length of the sides of the largest octagon contained in the figure. This distance spaced off on the circle. The cross lines are then drawn and the interior octagons will be formed as shown.

Those on the outer edge are formed by letting the cross lines extend beyond the large circle and from the center line as at A describe a circle cut ting these lines and connecting up the ends will form the octagon as shown.

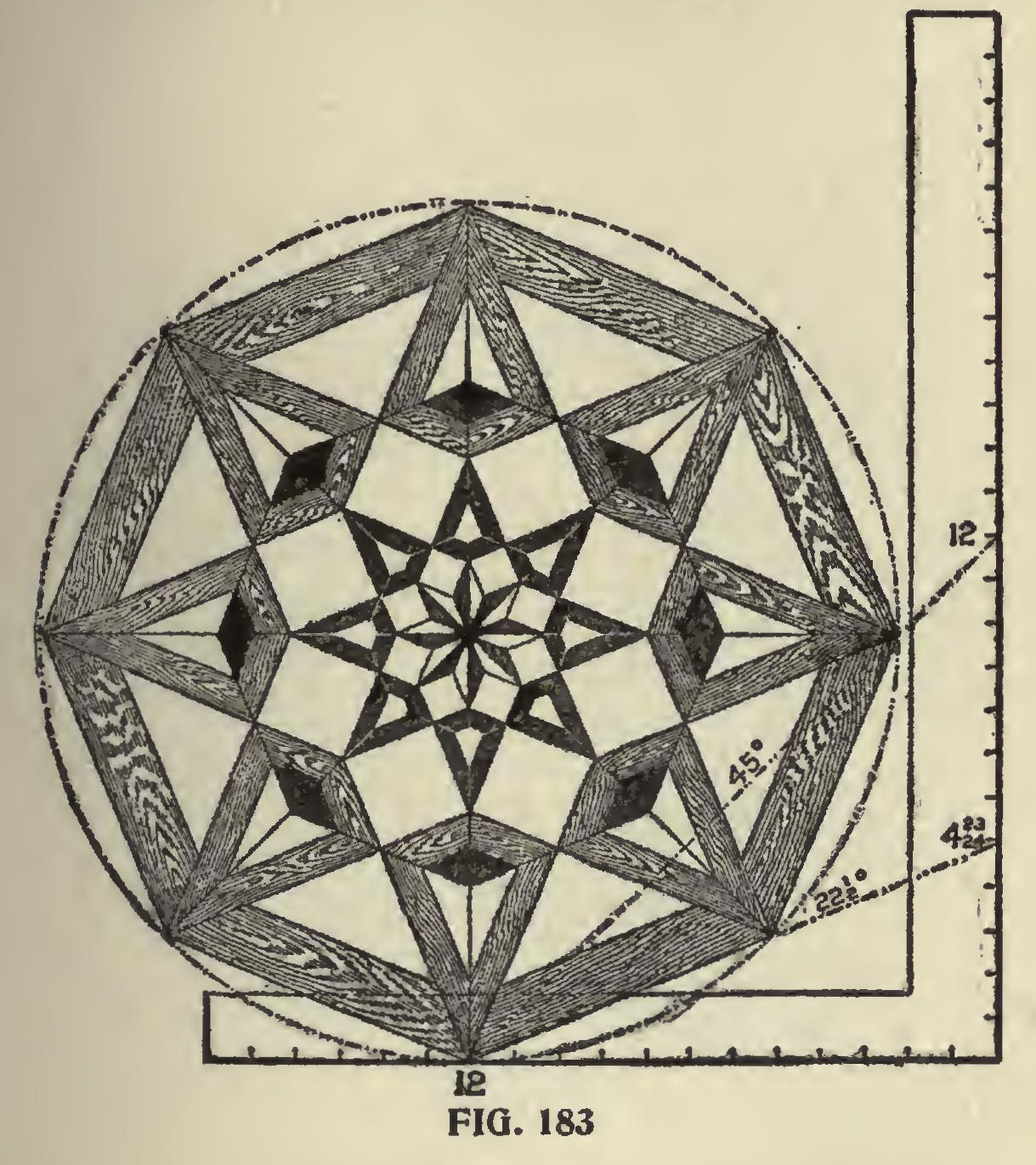

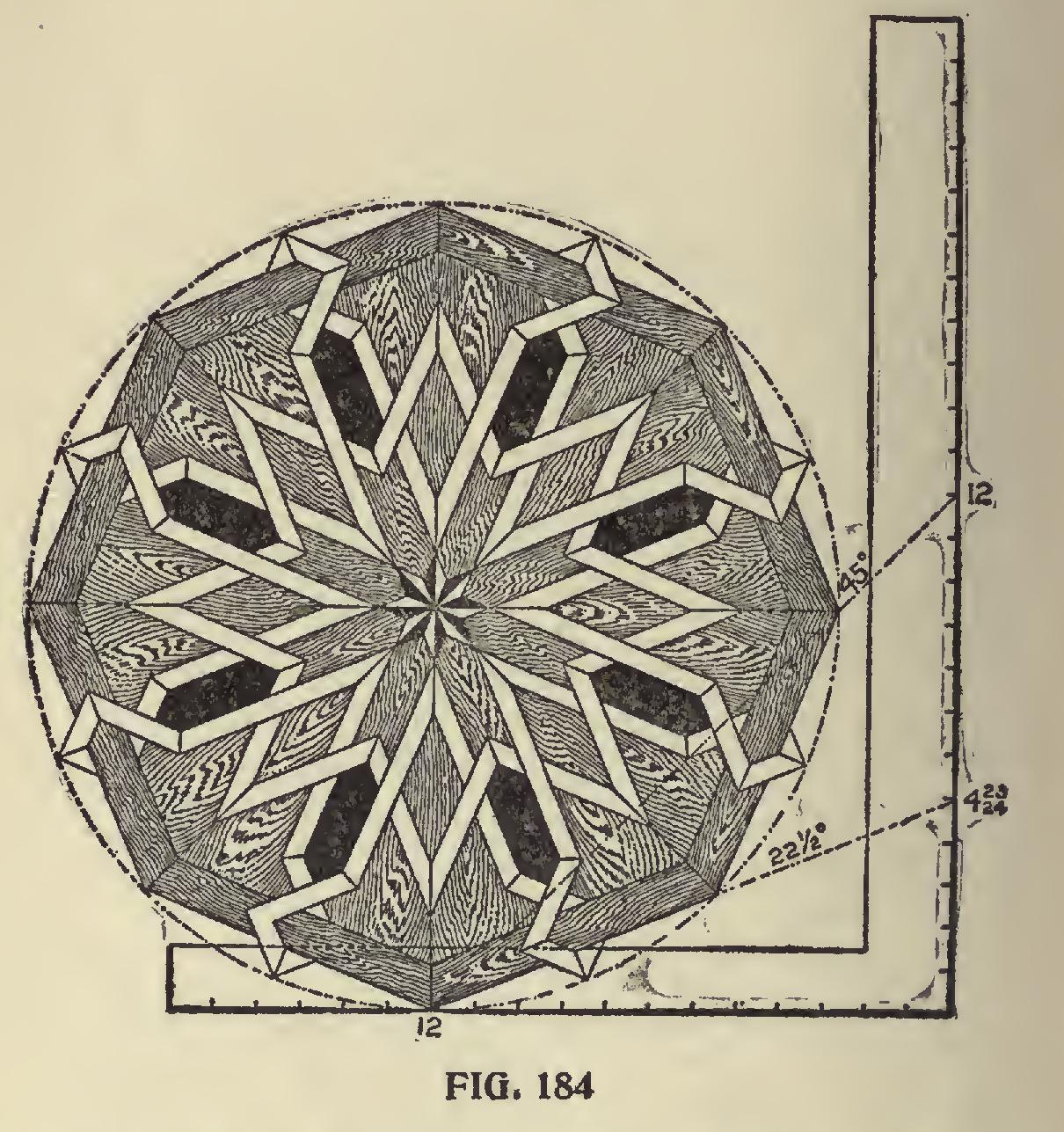

In Figs. 183 and 184 are shown patterns suit able for parquet or inlaid work. All of the miters contained in these designs can be had on the 22i and 45-degree lines and the figures shown on the square when applied will give all of the angles as well as the miters contained in these illustra tions.

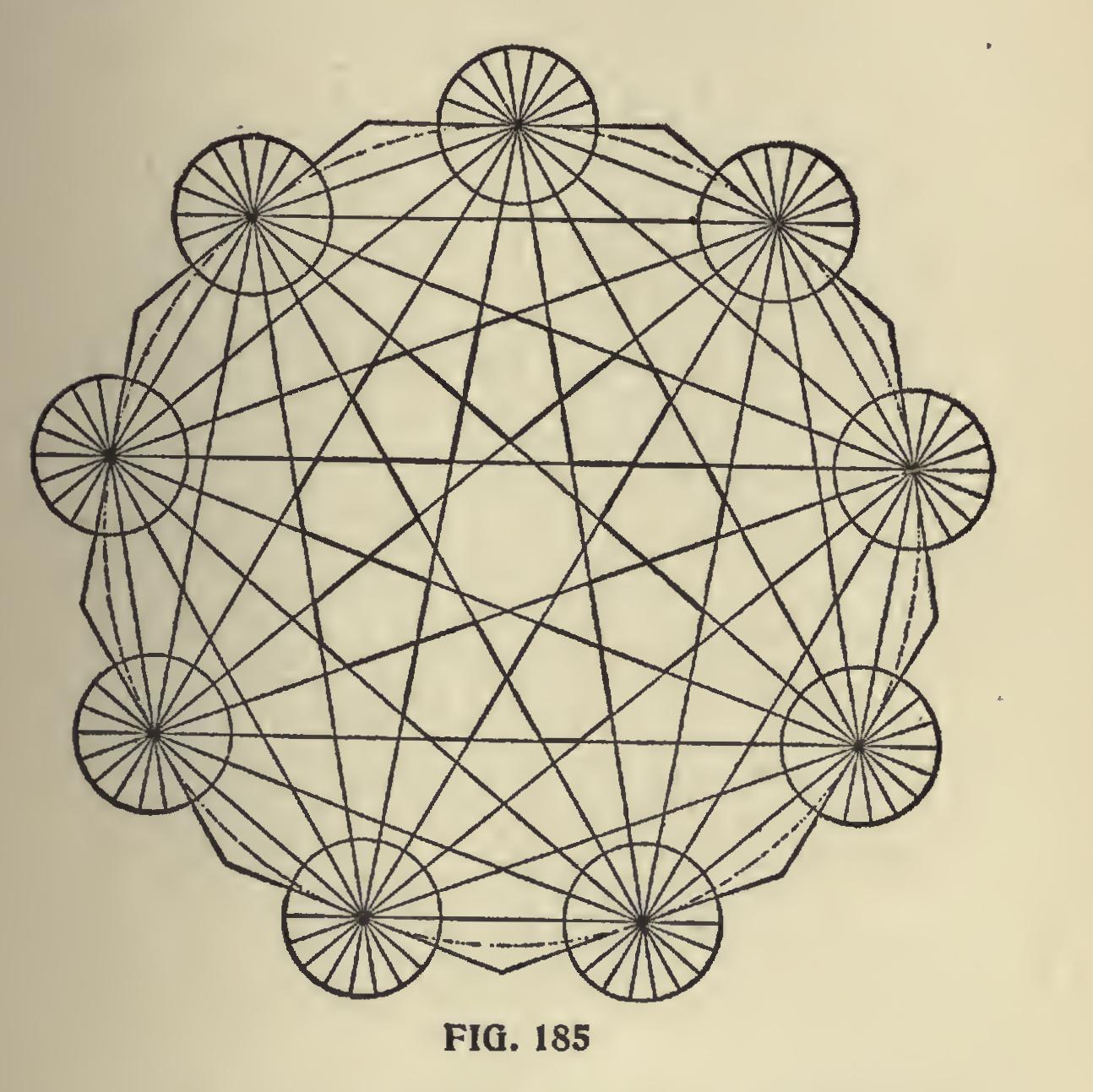

In Fig. 185 is shown an example in line work for the nonagon or nine-sided polygon. We have not shown the square in connection with this illustration, but the figures to use are for the 20 degree, because 9 is contained in 180 twenty times. The small circles are divided into eighteen parts because 20 is contained into 360 degrees eighteen times. A further explanation of this illustration would be useless, as it shows for itself.

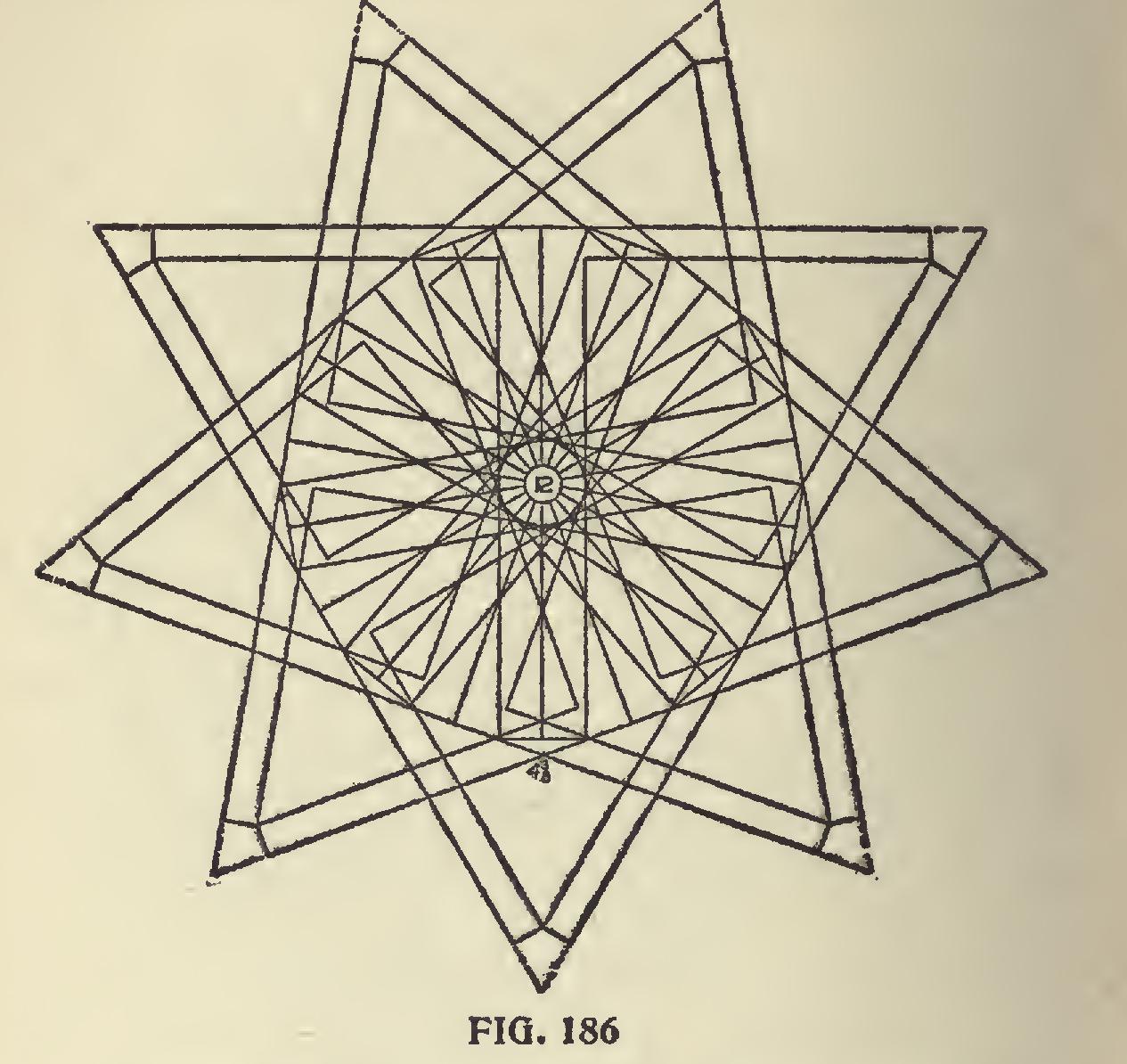

In Fig. 186 is shown a very pretty design made with eighteen squares. In this the center is at 12 on the blade and the intersection at 41 on the tongues, which is at the 20-degree line and rep resents the nonagon as will be seen by the forma tion of the tongues at the intersections. By extending the lines from the tongues as shown by the dotted lines will form a nine pointed star.

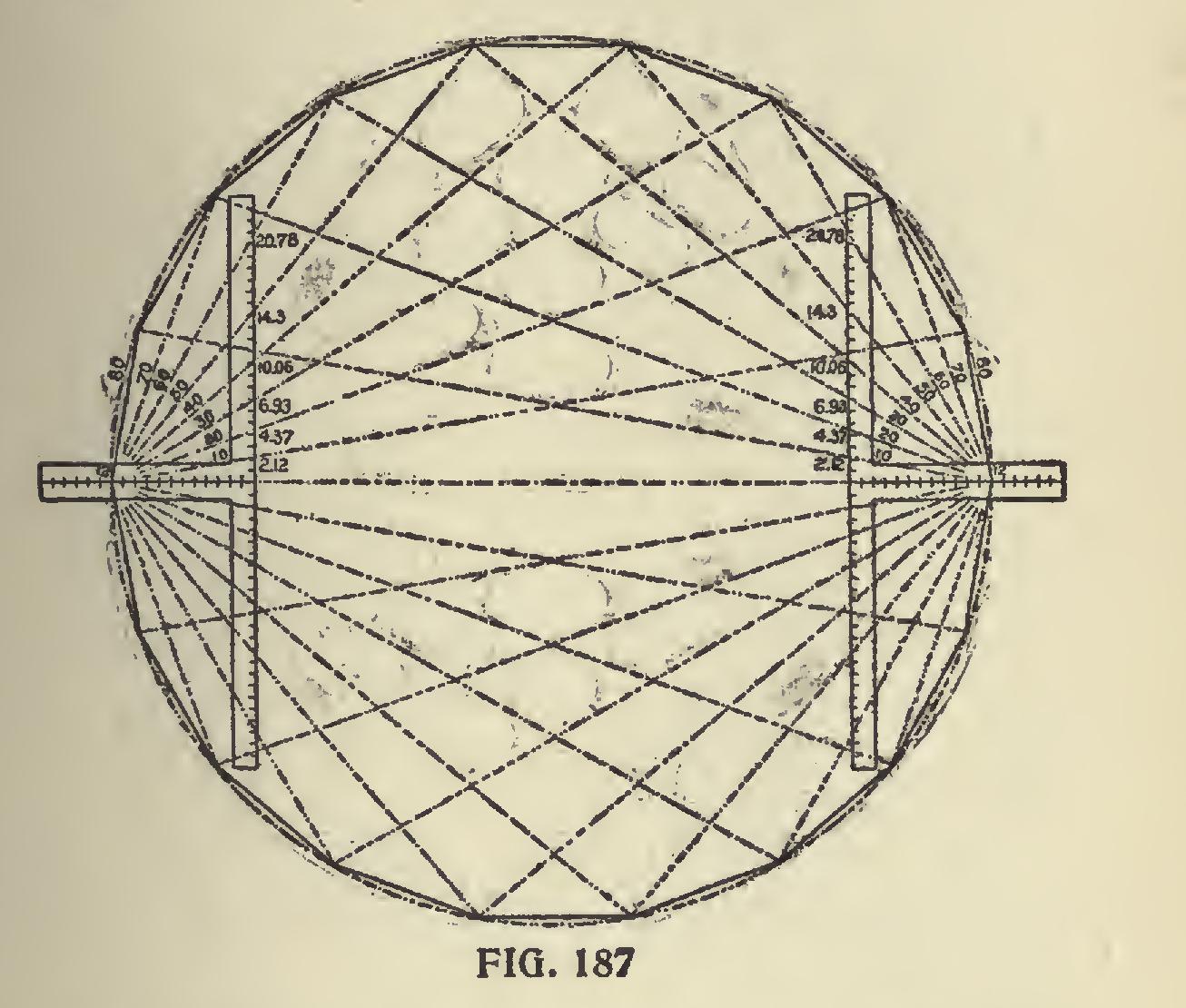

In Fig. 187 is shown four steel squares placed in pairs as shown with lines radiating from 12 on the tongues and intersecting the blade at 2.12 (4); 4.37 (41); 6.93 (6 11-12); 10.06 (10 1-12); 14.3 (14 7-24); and 20.78 (20 19-24), which rep resent the degree lines as being ten degrees apart. These lines extend out to meet its complement in other words, for example, the 30 degree inter sects the 60 degree line from the opposite side.

The intersections rest at 10 degrees apart on a circle with a diameter equal the distance from 12 to 12 on the tongues of the opposite squares, and by connecting the intersections forms a poly gon of eighteen sides. This rule applies to any other polygon, but is not a practical way of solving problems of this kind, because there are simpler ways of arriving at the same result.

With this we close with polygonal figures, as we think we have given enough to show that all work pertaining in any way to angles may be read ily obtained by the use of the common steel square.