Polygons and Miters

shown, pitch, fig, square, equal, lines, run and pipe

To Measure Inaccessible Distances by Aid of the Square.—The following is from an article written by Mr. A. W. Woods, of Lincoln, Neb., and is only modified so as to place the subject before our readers in its simplest form.

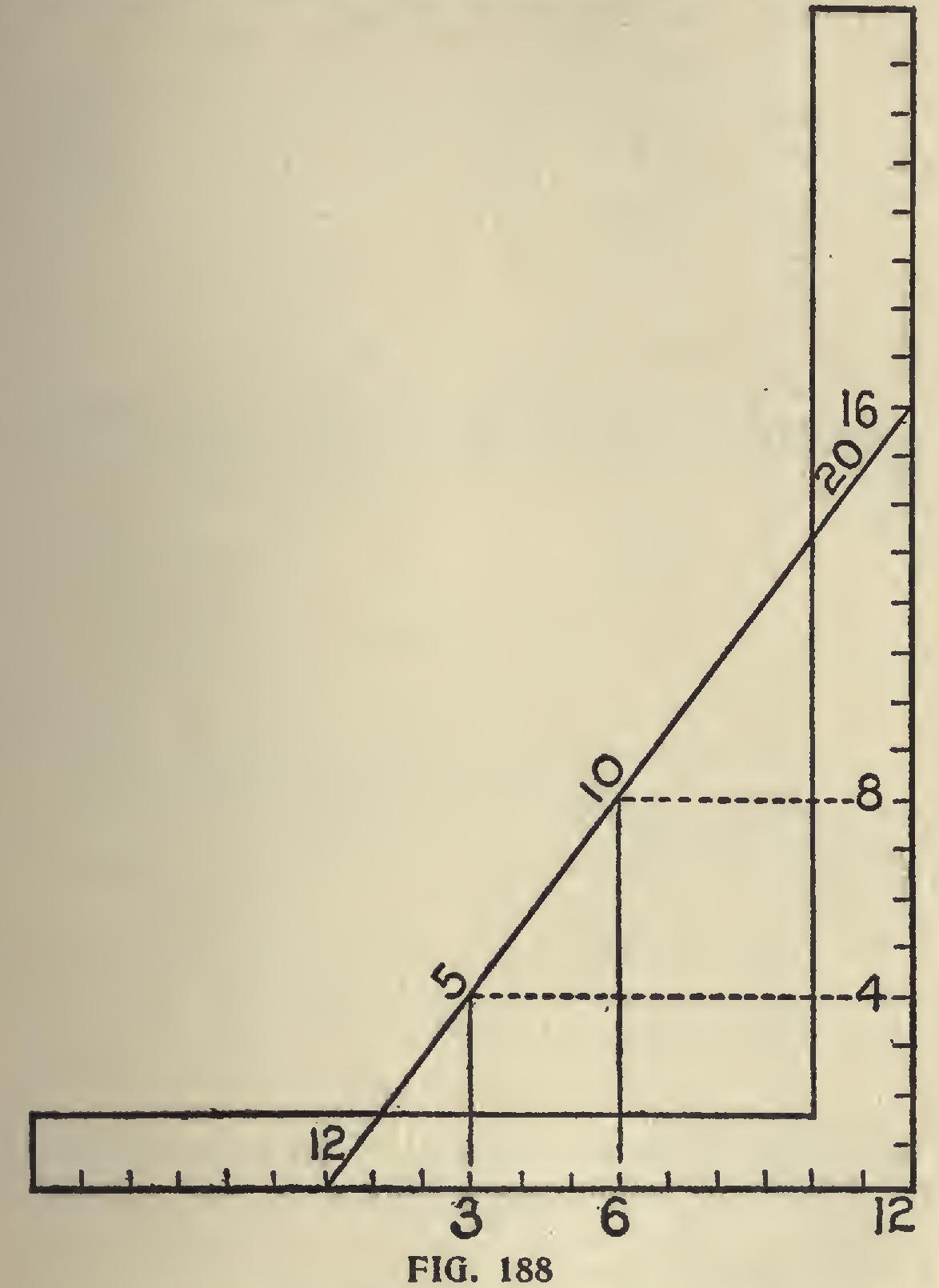

Every mechanic knows that a triangle whose sides measure 6, 8 and 10 forms a true right angle and is the method commonly used in squaring foundations. But how many ever stopped to think what other figures on the square will give the same result? By referring to trigonometry we find only three places, using 12 inches on the tongue as a basis and measuring to the inches on the blade that do not end in fractions of one inch on the hypothenuse side. They are as follows : 12 to 5 equals 13, 12 to 9 equals 15, and 12 to 16 equals 20.

Now, as we usually use a 10-foot pole to square up a foundation, we find that all of the above contain lengths greater than our pole, so we must take their proportions. The first con tain numbers not divisible without fractions, consequently we will pass on to the next. We find that three is the only number that will equally divide all the numbers with quotients, as follows: 4, 3 and 5, but these are too small to obtain the best results. Now let us examine 12, 16, and 20. They are even numbers, and are divisible by 2 and 4, Fig. 188. If we take half their dimensions we have 6, 8, 10.

These being convenient lengths and easily remembered, custom has settled on these figures.

There are other places that 6, 8, and 10 can be used to advantage.

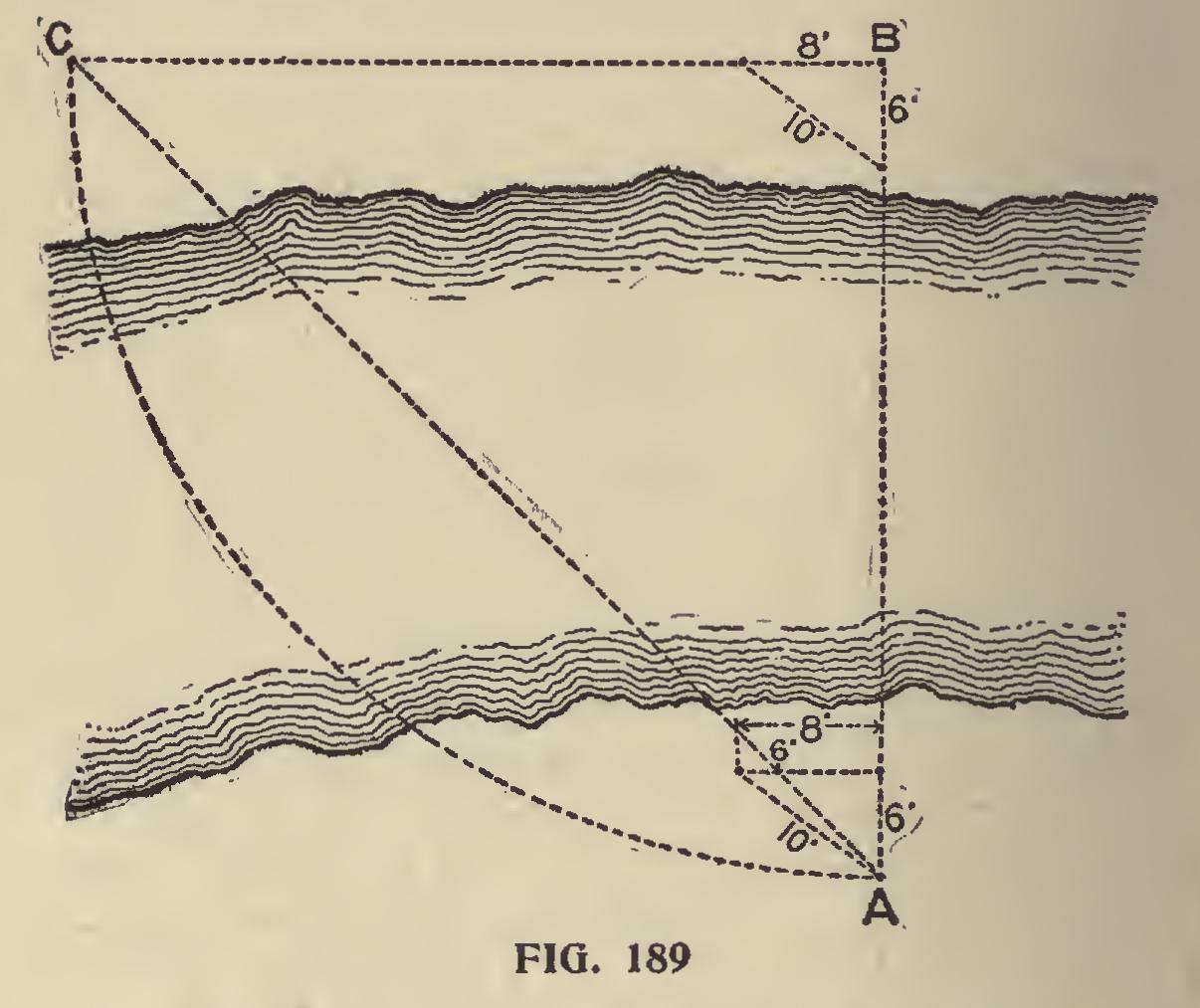

To Find the Distance Across a Body of Water.— Suppose for some reason we want to know the distance across a body of water. We cannot wade it, neither can we depend on a line stretched across because when it is restretched on an acces sible place of measurement we have no way of determining when it is drawn to the same tension. Now, referring to Fig. 189, we want to find the distance from A to B. Lay off the angle of 6, 8, and 10, at both A and B, as shown.

Since the base and perpendicular of a right angled triangle are of equal lengths when the hypothenuse rests at 45 degrees with the former, we measure off 6 feet on the 8-foot side as shown, and this will be the point of sight from A. With a man sighting from both A and B, a third sets the stake at C. Then B C must be the same length as A B. (The arc is shown to prove the accuracy of the diagram.) By measuring from A and B to the water's edge and subtracting the amount from B C will be given the width of the body of water.

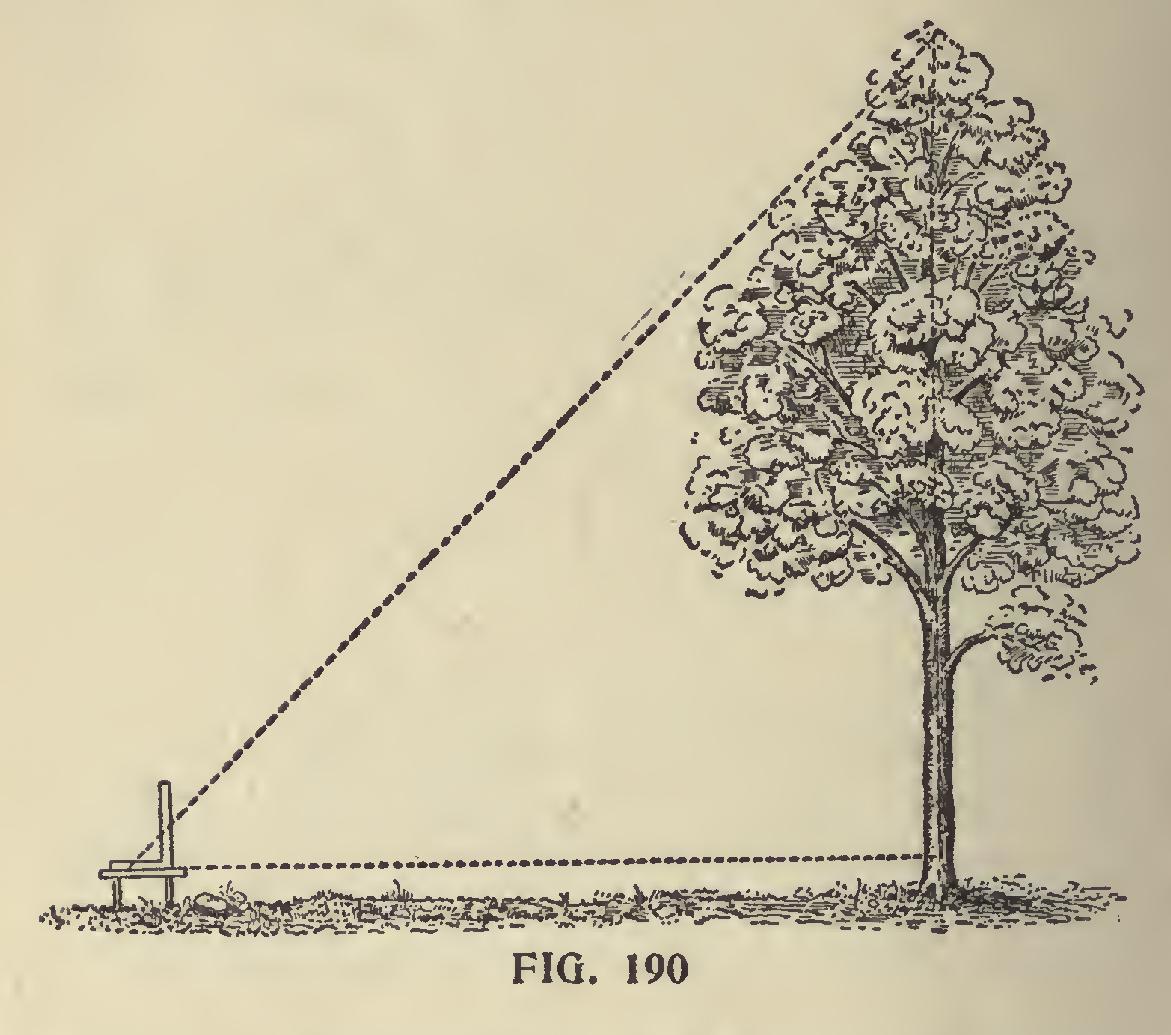

To Find the Height of a Tree.—Fig. 190 illus trates how a tree or inaccessible height can be measured on the same principle with the aid of the steel square. Take a straight-edge and fasten at any of the equal figures on the tongue and blade. Level and set as shown, and the base will be equal to the perpendicular.

Along with the foregoing we quote from another article by Mr. Woods showing some other possibilities of the steel square.

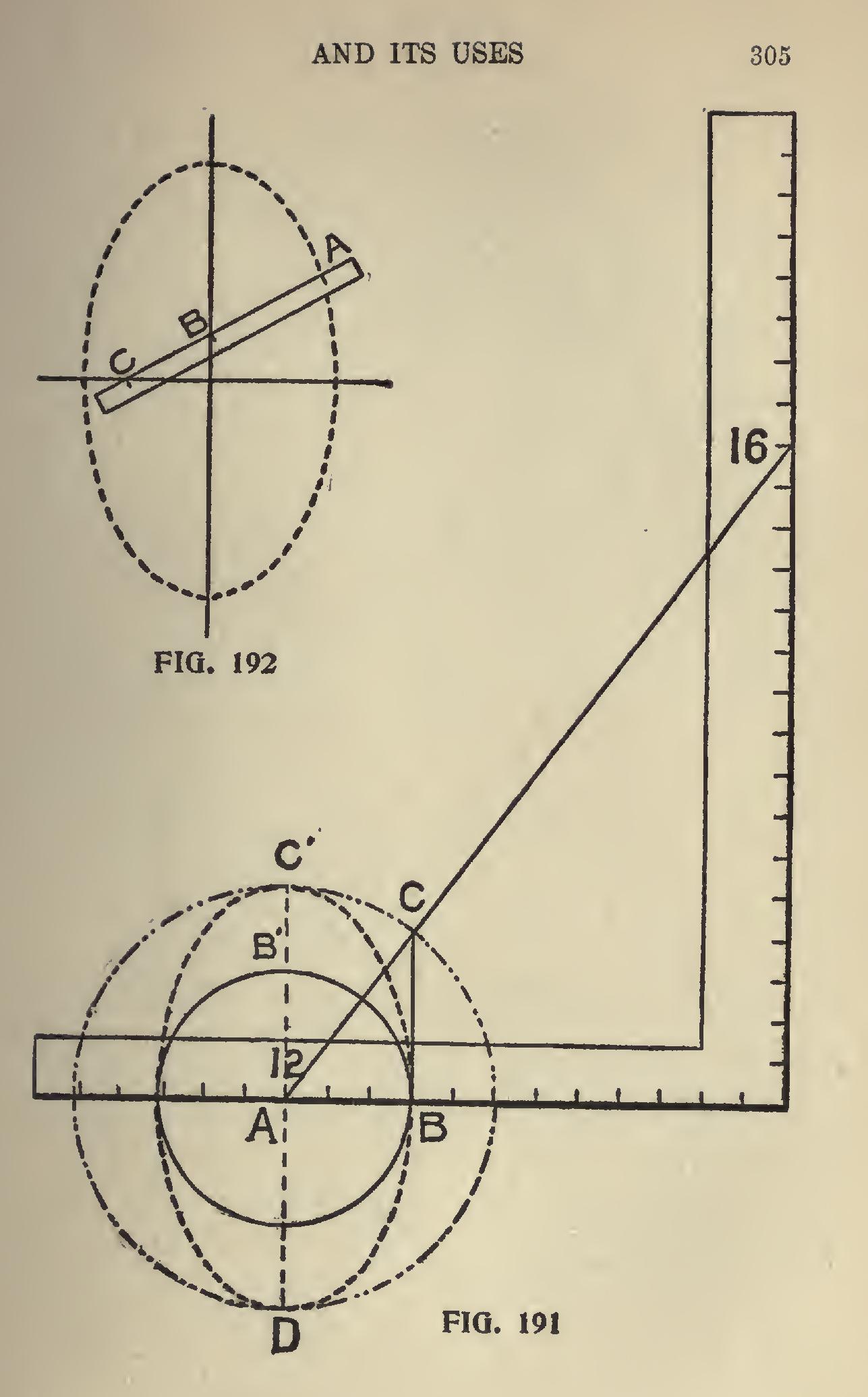

To Find a Required Opening in a Pitched Roof.— An opening for a round pipe in a pitched roof or partition at any angle may be found as shown in Fig. 191. Here we have a 6-inch pipe inter secting a two-thirds pitch. A line from 12 to 16 on the square represents the pitch. Now with 12 as center and with radius equal to one-half of the diameter of the pipe draw a circle and square up from the tongue to the pitch, as shown at B C.

Then A B represents one-half of the short diameter, and A C one-half of the long diameter. Now to make our illustration more clear we will transfer these lengths to a line at right angles with the tongue, crossing at 12.

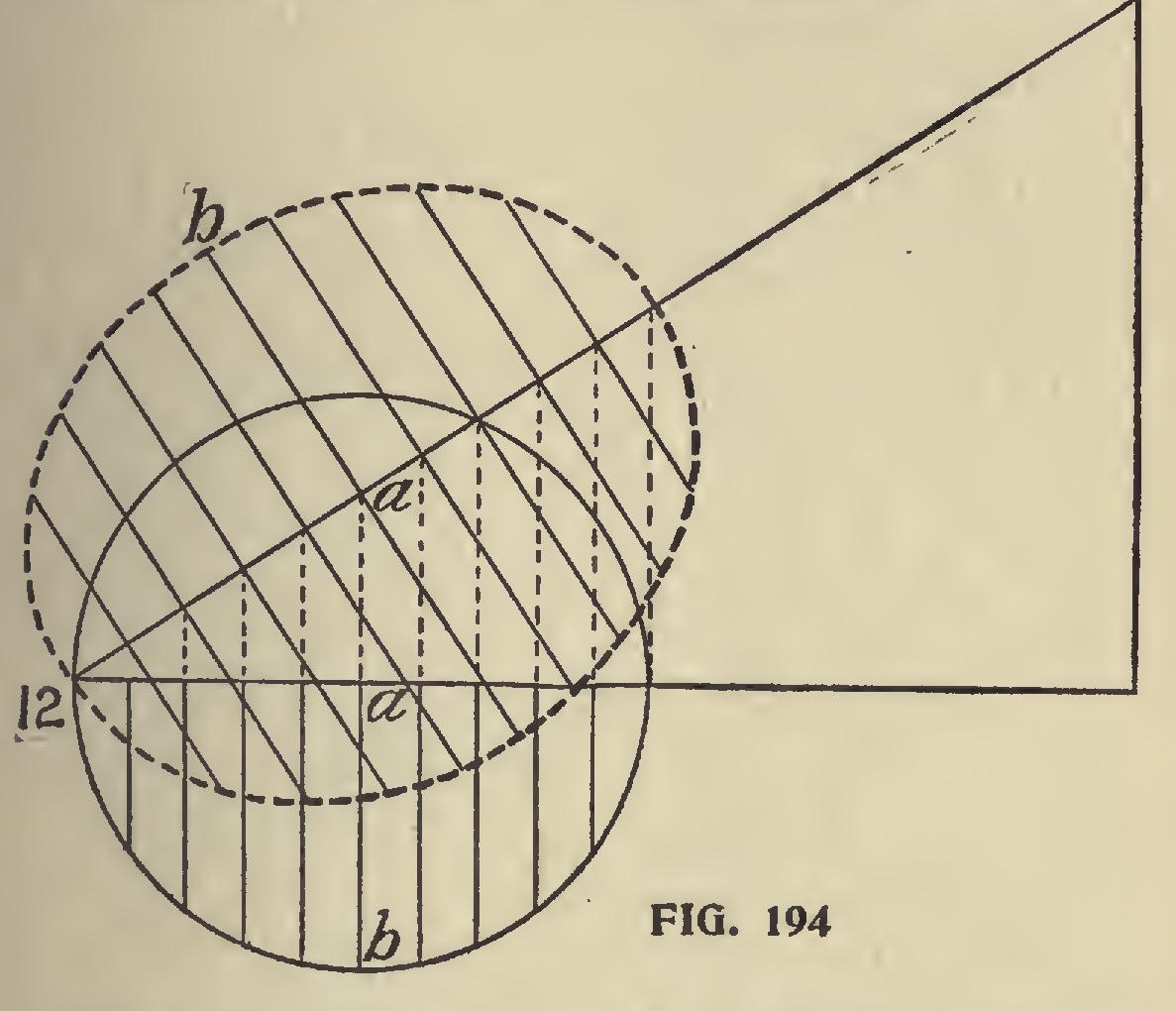

There are several ways of finding the correspond ing opening. Probably as good a method as any is that shown in Fig. 192, which is as follows : Take a straight edge, and on *it space off A, B", C", as shown in Fig. 191. Now draw a line equal to the long dia meter, C D, and bisect it at right angles, and to these lines apply the straight-edge, as shown in Fig. 192. Always keeping B C on the lines and marking at A will describe the required opening. The steeper the pitch the longer will be the required opening. In Fig. 193 is shownthe same formula, but with the one-third pitch and a 10-inch pipe. Fig. 194 shows another method of obtaining the opening, which is as follows : Lay off the run, rise and pitch, and with one-half the diameter of the pipe as radius, with the pencil point resting at 12, and center on run, draw a semi-circle. Divide the diameter into any number of spaces and through these run lines at right angles with the run from the circle to the pitch. At point of intersection on the pitch draw lines on either side at right angles and on this meas ure equal the length of the corresponding lines of the semi-circle, as at A B. Run an off-hand curve, touching these points, and you will have the required opening.