The Spermatozoon

nucleus and flagellum

Reviewing these facts from a physiological point of view, we may arrange the parts of the spermatozoon under two categories as follows:— t. The essential structures which play a direct part in fertilization. These are : (a) The nucleus, which contains the chromatin and is to be regarded as the vehicle of inheritance.

(h) The centrosome, certainly contained in the middle-piece as a rule, though perhaps lying in the tip in some cases. This is the fertilizing element par excellence, in Boveri's sense, since when introduced into the egg it causes the development of the amphiaster by which the egg divides. 2. The accessory structures, which play no direct part in fertilization, viz. : (a) The apex or spur, by which the spermatozoon attaches itself to the egg or bores its way into it.

(b) The tail, a locomotor organ which carries the nucleus and centrosome, and, as it were, deposits them in the egg at the time of fertilization. There can be little doubt that the substance of the flagellum is contractile, and that its movements are of the same nature as those of ordinary cilia. Ballowitz's discovery of its fibrillated structure is therefore of great interest, as indicating its structural as well as physiological similarity to a muscle-fibre. Moreover, as will appear beyond, it is nearly certain that the contractile fibrillae are derived from the attraction-sphere of the mother-cell, and therefore arise in the same manner as the archoplasm-fibres of the mitotic figure — a conclusion of especial interest in its relation to Van Beneden's theory of mitosis (p. 70).

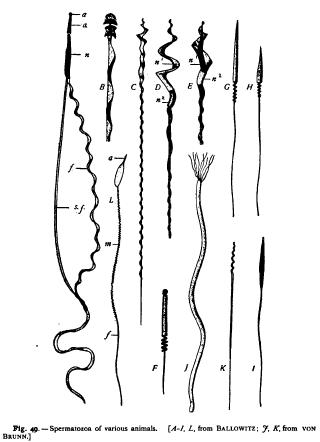

Tailed spermatozoa conforming more or less nearly to the type just described are with few exceptions found throughout the Metazoa from the coelenterates up to man ; but they show a most surprising diversity in form and structure in different groups of animals, and the homologies between the different forms have not yet been fully determined. The simpler forms, for example those of echinoderms and some of the fishes (Figs. 48 and 74), conform very nearly to the foregoing description. Every part of the spermatozoon may, howA. (At the left). Beetle (Capis), partly macerated to show structure of flagellum ; it consists of a supporting fibre (s.f.) and a fin-like envelope ( j.) ; n. nucleus ; a. a. apical body divided into two parts (the posterior of these is perhaps a part of the nucleus). B. Insect (Calathus),

with barbed head and fin-membrane. C. Bird (Phyllopneuste). D. Bird (Muscicapa), showing spiral structure ; nucleus divided into two parts (ni, ; no distinct middle-piece. E. Bulfinch ; spiral membrane of head. F. Gull (Lanus) with spiral middle-piece and apical knob. G. IL Giant spermatozoon and ordinary form of Tadorna. I. Ordinary form of the same stained, showing apex, nucleus, middle-piece and flagellum. 7. " Vermiform spermatozoon " and, X, ordinary spermatozoon of the snail Paludina. L. Snake (Coluber), showing apical body (a), nucleus, greatly elongated middle-piece (m), and flagellum (f).

ever, vary more or less widely from it (Figs. 48-5o). The head (nucleus) may be spherical, lance-shaped, rod-shaped, spirally twisted, hook-shaped, hood-shaped, or drawn out into a long filament ; and it is often divided into an anterior and a posterior piece of different staining capacity, as is the case with many birds and mammals. The apex sometimes appears to be wanting — e.g. in some fishes (Fig. 48). When present, it is sometimes a minute rounded knob, sometimes a sharp stylet, and in some cases terminates in a sharp barbed spur by which the spermatozoon appears to penetrate the ovum (Triton). In the mammals it seems to be represented by a cap-like structure, the so-called "head-cap," which in some forms covers the anterior end of the nucleus. It is sometimes divided into two distinct parts, a longer posterior piece and a knob-like anterior piece (insects, according to Ballowitz).

The middle-piece or connecting-piece shows a like diversity (Figs. 48-50). In many cases it is sharply differentiated from the flagellum, being sometimes nearly spherical, sometimes flattened like a cap against the nucleus, and sometimes forming a short cylinder of the same diameter as the nucleus, and hardly distinguishable from the latter until after staining (newt, earthworm). In other cases it is very long (reptiles, some mammals), and is scarcely distinguishable from the flagellum. In still others (birds, some mammals) it passes insensibly into the flagellum, and no sharply marked limit between them can be seen. In many of the mammals the long connecting-piece is separated from the head by a narrow " neck " in which the end-knobs lie, as described below.