Oogenesis and Spermatogenesis Reduction of the Chromosomes

maturation and phenomena

OOGENESIS AND SPERMATOGENESIS. REDUCTION OF THE CHROMOSOMES Van Beneden's epoch-making discovery that the nuclei of the conjugating germ-cells contain each one-half the number of chromosomes characteristic of the body-cells has now been extended to so many plants and animals that it may probably be regarded as a universal law of development. The process by which the reduction in number is effected, forms the most essential part of the phenomena of maturation by which the germ-cells are prepared for their union. No phenomena of cell-life possess a higher theoretical interest than these. For, on the one hand, nowhere in the history of the cell do we find so unmistakable and striking an adaptation of means to ends or one of so marked a prophetic character, since maturation looks not to the present but to the future of the germ-cells. On the other hand, the chromatin-reduction suggests problems relating to the morphological constitution of nucleus and chromatin which have an important bearing on all theories of development, and which now stand in the foreground of scientific discussion among the most debatable and interesting of biological problems.

It must be said at the outset that the phenomena of maturation belong to one of the most difficult fields of cytological research, and one in which we are confronted not only by diametrically opposing theoretical views, but also by apparently contradictory results of observation.

Two fundamentally different views have been held of the manner in which the reduction is effected. The earlier and simpler view, which was somewhat doubtfully suggested by Boveri ('87, 1), and has been more recently supported by Van Bambeke ('94) and some others, assumed an actual degeneration or casting out of half the chromosomes during the growth of the germ-cells — a simple and easily intelligible process. The whole weight of the evidence now goes to show, however, that this view cannot be sustained, and that reduction is effected by a rearrangement and redistribution of the nuclear substance without loss of any of its essential constituents. It is true that a large amount of chromatin is lost during the growth of the egg.' It is nevertheless certain that this loss is not directly connected with the process of reduction ; for, as Hertwig and others have shown, no such loss occurs during spermatogenesis, and even in the oogenesis the evidence is clear that an explanation must be sought in another direction. We have advanced a certain distance

towards such an explanation and, indeed, apparently have found it in a few specific cases. Yet when the subject is regarded as a whole, the admission must be made that the time has not yet come for an understanding of the phenomena, and the subject must therefore be treated in the main from an historical point of view.

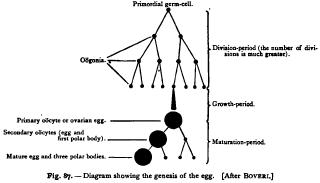

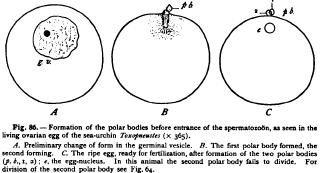

The general phenomena of maturation fall under two heads ; viz. oogenesis, which includes the formation and maturation of the ovum, and spermatogenesis, comprising the corresponding phenomena in case of the spermatozoon. Recent research has shown that maturation conforms to the same type in both sexes, which show as close a parallel in this regard as in the later history of the germ-nuclei. Stated in the most general terms, this parallel is as In both sexes the final reduction in the number of chromosomes is effected in the course of the last two cell-divisions by which the definitive germ-cells arise, each of the four cells thus formed having but half the usual number of chromosomes. In the female but one of the four cells forms the " ovum " proper, while the other three, known as the polar bodies, are minute, rudimentary, and incapable of development (Figs. 64, 71, 86). In the male, on the other hand, all four of the cells become functional spermatozoa. This difference between the two sexes is probably due to the physiological division of labour between the germcells, the spermatozoa being motile and very small, while the egg contains a large amount of protoplasm and yolk, out of which the main mass of the embryonic body is formed. In the male, therefore, all of the four cells may become functional ; in the female the functions of development have become restricted to but one of the four, while the others have become rudimentary (cf. p. 182). The polar bodies are therefore to be regarded as abortive eggs — a view first put forward by Mark in 1881, and ultimately adopted by nearly all investigators.