Oogenesis and Spermatogenesis Reduction of the Chromosomes

spermatozoa and division

Reduction in the Male. Spermatogenesis

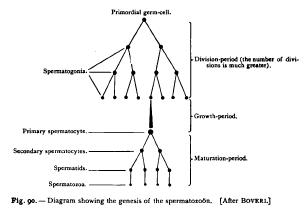

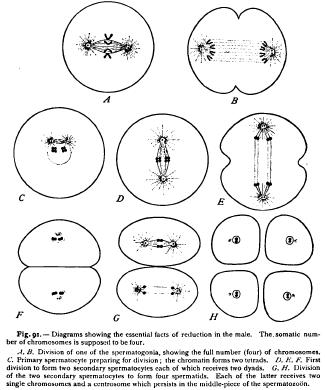

The researches of Platner ('89), Boveri, and especially of Oscar Hertwig ('9o, I) have demonstrated that reduction takes place in the male in a manner almost precisely parallel to that occurring in the female. Platner first suggested ('89) that the formation of the polar bodies is directly comparable to the last two divisions of the sperm mother-cells (spermatocytes). In the following year Boveri reached the same result in Ascaris, stating his conclusion that reduction in the male must take place in the "grandmother-cell of the spermatozoon, just as in the female it takes place in the grandmother-cell of the egg," and that the egg-formation and sperm-formation really agree down to the smallest detail ('90, p. 64). Later in the same year appeared Oscar Hertwig's splendid work on the spermatogenesis of Ascaris, which established this conclusion in the most striking manner. Like the ova, the spermatozoa arc descended from primordial germ-cells which by mitotic division give rise to the spermatogonia from which the spermatozoa are ultimately formed (Fig. 9o). Like the oogonia, the spermatogonia continue for a time to divide with the usual (somatic) number of chromosomes ; i.e. four in Ascaris megalocephala bivalens. Ceasing for a time to divide, they now enlarge considerably to form spermatocytes, each of which is morphologically equivalent to an unripe ovarian ovum, or oocyte. Each spermatocyte finally divides twice in rapid succession, giving rise first to two daughter-spermatocytes and then to four spermatids, each of which is directly converted into a single spermatozoon. The history of the chromatin in these two divisions is exactly parallel to that in the formation of the polar bodies (Figs. 91, 92). From the chromatin of the spermatocyte are formed a number of tetrads equal to one-half the usual number of chromosomes. Each tetrad is halved at the first division to form two dyads which pass into the respective daughter-spermatocytes. At the ensuing division, which occurs without the previous formation of a resting reticular nucleus, each dyad is halved to form two single chromosomes which enter the respective spermatids (ultimately spermatozoa). From each spermatocyte, therefore, arise four spermatozoa, and each sperm-nucleus receives half the usual number of single chromosomes. The parallel with the egg-reduction is complete.

These facts leave no doubt that the spermatocyte is the morphological equivalent of the oocyte or immature ovarian egg, and that the group of four spermatozoa to which it gives rise is equivalent to the ripe egg plus the three polar bodies. Hertwig was thus led to the following beautifully clear and simple conclusion : " The polar bodies are abortive eggs which are formed by a final process of division from the egg-mother-cell (oocyte) in the same manner as the spermatozoa are formed from the sperm-mother-cell (spermatocyte). But while in the latter case the products of the division are all used as functional spermatozoa, in the former case one of the products of the egg-mother-cell becomes the egg, appropriating to itself the entire mass of the yolk at the cost of the others which persist in rudimentary form as the polar 3. Theoretical Significance of Maturation Up to this point the facts are clear and intelligible. When, however, we attempt a more searching analysis by considering the origin of the tetrads and the ultimate meaning of reduction, we find ourselves in a labyrinth of conflicting observations and hypotheses from which no exit has as yet been discovered. And we may in this case most readily approach the subject by considering its theoretical aspect at the outset.

The process of reduction is very obviously a provision to hold constant the number of chromosomes characteristic of the species ; for if it did not occur, the number would be doubled in each succeeding generation through union of the germ-cells. But why should the number be constant ? • In its modern form this problem was first attacked by Weismann in 1885, and again in 1887, though many earlier hypotheses regarding the meaning of the polar bodies had been put forward.' His interpretation was based on a remarkable paper published by Wilhelm Roux in in which are developed certain ideas which afterwards formed the foundation of Weismann's whole theory of inheritance and development. Roux argued that the facts of mitosis are only explicable under the assumption that chromatin is not a uniform and homogeneous substance, but differs qualitatively in different regions of the nucleus ; that the collection of the chromatin into a thread and its accurate division into two halves is meaningless unless the chromatin in different regions of the thread represents different qualities which are to be divided and distributed to the daughtercells according to some definite law. He urged that if the chromatin were qualitatively the same throughout the nucleus, direct division would be as efficacious as indirect, and the complicated apparatus of mitosis would be superfluous. Roux and Weismann, each in his own way, subsequently elaborated this conception to a complete theory of inheritance and development, but at this point we may confine our attention to the views of Weismann. The starting-point of his theory is the hypothesis of De Vries that the chromatin is a congeries or colony of invisible self-propagating vital units or biophores somewhat like Darwin's " gemmules " (p. 3o3), each of which has the power of determining the development of a particular quality. Weismann conceives these units as aggregated to form units of a higher order known as " determinants," which in turn are grouped to form I Of these we need only consider at this point the very interesting suggestion of Minot ('77), afterwards adopted by Van Beneden ('83), that the ordinary cell is hermaphrodite, and that maturation is for the purpose of producing a unisexual germ-cell by dividing the mother-cell into its sexual constituents, or "genoblasts." Thus, the male element is removed from the egg in the polar bodies, leaving the mature egg a female. In like manner he believed the female element to be cast out during spermatogenesis (in the " Sertoli cells"), thus rendering the spermatozoa male. By the union of the germ-cells in fertilization the male and female elements are brought together so that the fertilized egg or o8sperm is again hermaphrodite or neuter. This ingenious view was independently advocated by Van Beneden in his great work on Ascaris ('83). A fatal objection to it, on which both Strasburger and Weismann have insisted, lies in the fact that male as well as female qualities are transmitted by the egg-cell, while the sperm-cell also transmits female qualities. The germ-cells are therefore non-sexual; they are physiologically as well as morphologically equivalent. The researches of Hertwig, Brauer, and Boveri show, moreover, that in "'marls, at any rate, all of the four spermatids derived from a spermatocyte become functional spermatozoa, and the beautiful parallel between spermatogenesis and oogenesis thus established becomes meaningless under Minot's view. This hypothesis must, therefore, in my opinion, he abandoned.