Oogenesis and Spermatogenesis Reduction of the Chromosomes

polar and egg

Reduction in the Female. Formation of the Polar Bodies

As described in Chapter III., the egg arises by the division of cells descended from the primordial egg-cells of the maternal organism, and these may be differentiated from the somatic cells at a very early 1 The parallel was first clearly pointed out by Platner in :889, and was brilliantly demonstrated by Oscar Hertwig in the following year.

period, sometimes even in the cleavage-stages. As development proceeds, each primordial cell gives rise, by division of the usual mitotic type, to a number of descendants known as oogonia (Fig. 87), which are the immediate predecessors of the ovarian egg. At a certain period these cease to divide. Each of them then grows to form an ovarian egg, its nucleus enlarging to form the germinal vesicle, its cytoplasm becoming more or less laden with food-matters (yolk or deutoplasm), while egg-membranes may be formed around it. The ovum may now be termed the oocyte(Boveri) or ovarian egg.

In this condition the egg-cell remains until near the time of fertilization, when the process of maturation proper — i.e. the formation of the polar bodies— takes place. In some cases, e.g. in the sea-urchin, the polar bodies are formed before fertilization while the egg is still in the ovary. More commonly, as in annelids, gasteropods, nematodes, they are not formed until after the spermatozoon has made its entrance ; while in a few cases one polar body may be formed before fertilization and one afterwards, as in the lamprey-eel, the frog, and Ampkioxus. In all these cases, the essential phenomena are the same. Two minute cells are formed, one after the other, near the upper or animal pole of the ovum (Figs. 71, 86); and in many cases the first of these divides into two as the second is formed (Fig. 64).

A group of four cells thus arises, namely, the mature egg, which gives rise to the embryo, and three small cells or polar bodies which take no part in the further development, are discarded, and soon die without further change. The egg-nucleus is now ready for union with the sperm-nucleus.

A study of the nucleus during these changes brings out the following facts. During the multiplication of the oogonia the number of chromosomes is, in some cases at any rate, the same as that occurring in the division of the somatic cells,' and the same number enters into the formation of the chromatic reticulum of the germinal vesicle. During the formation of the polar bodies this number becomes reduced to one-half, the nucleus of each polar body and the eggnucleus receiving the reduced number. In some manner, therefore, the formation of the polar bodies is connected with the process by which the reduction is effected. The precise nature of this process is, however, a matter which has been certainly determined in only a few cases.

We need not here consider the history of opinion on this subject further than to point out that the early observers, such as Purkinje, von Baer, Bischoff, had no real understanding of the process and believed the germinal vesicle to disappear at the time of fertilization.

To Butschli ('76,) Hertwig, and Giard ('77) we owe the discovery that the formation of the polar bodies is through mitotic division, the chromosomes of the equatorial plate being derived from the chromatin of the germinal vesicle.' In the formation of the first polar

body the group of chromosomes splits into two daughter-groups, and this process is immediately repeated in the formation of the second without an intervening reticular resting stage. The egg-nucleus therefore receives, like each of the polar bodies, one-fourth of the mass of chromatin derived from the germinal vesicle.

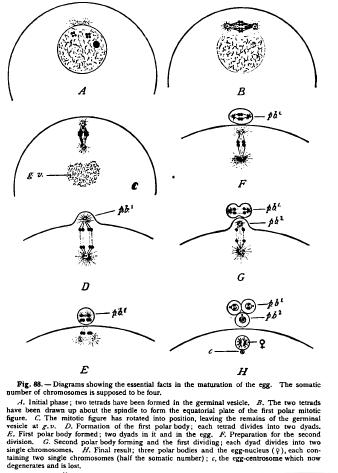

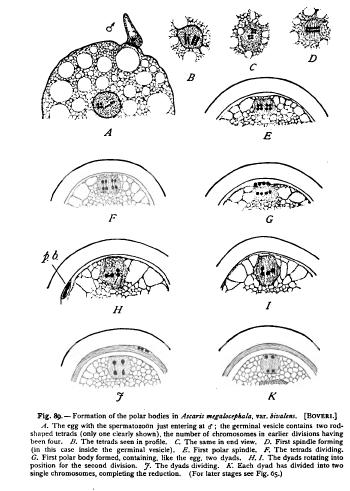

But although the formation of the polar bodies was thus shown to be a process of true cell-division, the history of the chromosomes was found to differ in some very important particulars from that of the tissue-cells. The essential facts, which were first accurately determined by Boveri in Ascaris ('87, 1), are in a typical case as follows (Figs. 88, 89) : As the egg prepares for the formation of the first polar body, the chromatin of the germinal vesicle groups itself in a number of masses, each of which splits up into a group of four bodies united by linin-threads to form a " quadruple group " or tetrad (Vierergruppe). The number of tetrads is always one-half the usual number of chromosomes. Thus in Ascaris (megalocephala, bivalens) the germinal vesicle gives rise to two tetrads, the normal number of chromosomes in the earlier divisions being four ; in the salamander and the frog there are twelve tetrads, the somatic number of chromosomes being twenty-four (Fleming, vom Rath), etc. As the first polar body forms, each of the tetrads is halved to form two double groups, or dyads, one of which remains in the egg while the other passes into the polar body. Both the egg and the first polar body therefore receive each a number of dyads equal to one-half the usual number of chromosomes. The egg now proceeds at once to the formation of the second polar body without previous reconstruction of the nucleus. Each dyad is halved to form two single chromosomes, one of which, again, remains in the egg while its sister passes into the polar body. Both the egg and the second polar body accordingly receive two single chromosomes (one-half the usual number), each of which is one-fourth of an original tetrad group. From the two remaining in the egg a reticular nucleus, much smaller than the original germinal vesicle, is now Essentially similar facts have now been determined in a considerable number of animals, though the form of the tetrads varies greatly, and there are some cases in which no actual tetrad-formation has been observed (apparently in the flowering plants). It is clear from the foregoing account that the numerical reduction of chromatin-masses takes place before the polar bodies are actually formed, through the operation of forces which determine the number of tetrads within the germinal vesicle. The numerical reduction is therefore determined in the grandmother-cell of the egg. The actual divisions by which the polar bodies are formed merely distribute the elements of the tetrads.