Physiological Relations of Nucleus and Cytoplasm

fragments and non-nucleated

PHYSIOLOGICAL RELATIONS OF NUCLEUS AND CYTOPLASM How nearly the foregoing facts bear on the problem of the formative power of the cell in a morphological sense is obvious, and they have in a measure anticipated certain conclusions regarding the role of nucleus and cytoplasm which we may now examine from a somewhat different point of view.

Brucke long ago drew a clear distinction between the chemical and molecular composition of organic substances, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, their definite grouping in the cell by which arises organization in a morphological sense. Claude Bernard, in like manner, distinguished between chemical synthesis, through which organic matters are formed, and morphological synthesis, by which they are built into a specifically organized fabric ; but he insisted that these two processes are but different phases or degrees of the same phenomenon, and that both are expressions of the nuclear activity. We have now to consider some of the evidence that the formative power of the cell, in a morphological sense, centres in the nucleus, and that this is therefore to be regarded as the especial organ of inheritance. This evidence is mainly derived from the comparison of nucleated and non-nucleated masses of protoplasm ; from the form, position and movements of the nucleus in actively growing or metabolizing cells ; and from the history of the nucleus in mitotic cell-division, in fertilization, and in maturation.

Experiments on Unicellular Organisms

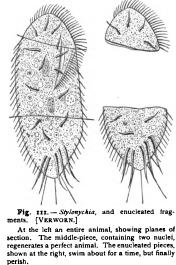

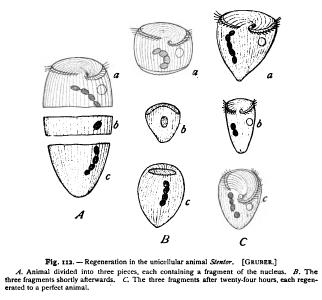

Brandt ('77) long since observed that enucleated fragments of Actinospharium soon die, while nucleated fragments heal their wounds and continue to live. The first decisive comparison between nucleated and non-nucleated masses of protoplasm was, however, made by Moritz Nussbaum in 1884 in the case of an infusorian, Oxytricha. If one of these animals be cut into two pieces, the subsequent behaviour of the two fragments depends on the presence or absence of the nucleus or a nuclear fragment. The nucleated fragments quickly heal the wound, regenerate the missing portions, and thus produce a perfect animal. On the other hand, enucleated fragments, consisting of cytoplasm only, quickly perish. Nussbaum therefore drew the conclusion that the nucleus is indispensable for the formative energy of the cell. The experiment was soon after repeated by Gruber ('85) in the case of Stentor, another infusorian, and with the same result (Fig. 112). Fragments possessing a large fragment of the nucleus completely regenerated within twenty-four hours. If the nuclear fragment were smaller, the regeneration proceeded more slowly. If no nuclear substance were present, no regeneration took place, though the wound closed and the fragment lived for a considerable time. The only exception— but it is a very significant one—was the case of individuals in which the process of normal fission had begun ; in these a non-nucleated fragment in which the formation of a new peristome had already been initiated healed the wound and completed the formation of the peristome. Lillie ('96) has recentlyfound that Stentor may by shaking be broken into fragments of all sizes, and that nucleated fragments as small as A- the volume of the entire animal are still capable of complete regeneration. All non-nucleated fragments perish.

These studies of Nussbaum and Gruber formed a prelude to more extended investigations in the same direction by Gruber, Balbiani, Hofer, and especially Verworn. Verworn ('88) proved that in Polystomella, one of the Foraminifera, nucleated fragments are able to repair the shell, while non-nucleated fragments lack this power. Balbiani ('89) showed that although non-nucleated fragments of infusoria had no power of regeneration, they might nevertheless continue to live and swim actively about for many days after the operation, the contractile vacuole pulsating as usual. Hofer ('89), experimenting on Amoba, found that non-nucleated fragments might live as long as fourteen days after the operation (Fig. 113). Their movements continued, but were somewhat modified, and little by little ceased, but the pulsations of the contractile vacuole were but slightly affected ; they lost more or less completely the capacity to digest food, and the power of adhering to the substratum. Nearly at the same time Verworn ('89) published the results of an extended comparative investigation of various Protozoa that placed the whole matter in a very clear light. His experiments, while fully confirming the accounts of his predecessors in regard to regeneration, added many extremely important and significant results. Non-nucleated fragments both of infusoria (e.g., Lachrymaria) and rhizopods (Polystornella, Thalassicolla) not only live for a considerable period, but perform perfectly normal and characteristic movements, show the same susceptibility to stimulus, and have the same power of ingulfing food, as the nucleated fragments. They lack, however, the power of digestion and secretion. Ingested food-matters may be slightly altered, but are never completely digested. The non-nucleated fragments are unable to secrete the material for a new shell (Polystomclla) or the slime by which the animals adhere to the substratum (Amoba, Difflugia, Polystomella). Beside these results should be placed the well-known fact that dissevered nerve-fibres in the higher animals are only regenerated from that end which remains in connection with the nerve-cell, while the remaining portion invariably degenerates.