Physiological Relations of Nucleus and Cytoplasm

cells and latter

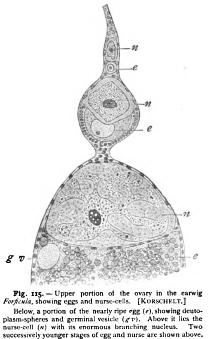

Regarding the position and movements of the nucleus, Korschelt reviews many facts pointing towards the same conclusion. Perhaps the most suggestive of these relate to the nucleus of the egg during its ovarian history. In many of the insects, as in both the cases referred to above, the egg-nucleus at first occupies a central position, but as the egg begins to grow, it moves to the periphery on the side turned towards the nutritive cells. The same is true in the ovarian eggs of some other animals, good examples of which are afforded by various coelenterates, c.g. in medusa (Claus, Hertwig) and actinians (Korschelt, Hertwig), where the germinal vesicle is always near the point of attachment of the egg. Most suggestive of all is the case of the water-beetle Dytiscus, in which Korschelt was able to observe the movements and changes of form in the living object. The eggs here lie in a single series alternating with chambers of nutritive cells. The latter contain granules which are believed by Korschelt to pass into the egg, perhaps bodily, perhaps by dissolving and entering in a liquid form. At all events, the egg contains accumulations of similar granules, which extend inwards in dense masses from the nutritive cells to the germinal vesicle, which they may more or less completely surround. The latter meanwhile becomes amoeboid, sending out long pseudopodia, which are always directed towards the principal mass of granules (Fig. 58). The granules could not be traced into the nucleus, but the latter grows rapidly during these changes, proving that matter must be absorbed by it, probably in a liquid form.' All of these and a large number of other observations in the same direction lead to the conclusion that the cell-nucleus plays an active part in nutrition, and that it is especially active during its constructive phase. On the whole, therefore, the behaviour of the nucleus in this regard is in harmony with the result reached by experiment on the one-celled forms, though it gives in itself a far less certain and convincing result.

We now turn to evidence which, though less direct than the experimental proof, is scarcely less convincing. This evidence, which has been exhaustively discussed by Hertwig, Weismann, and Strasburger, is drawn from the history of the nucleus in mitosis, fertilization, and maturation. It calls for only a brief review here, since the facts have been fully described in earlier chapters.

The Nucleus in Mitosis

To Wilhelm Roux ('83) we owe the first clear recognition of the fact that the transformation of the chromatic substance during mitotic division is manifestly designed to effect a precise division of all its parts, i.e. a panmeristic division as opposed to a mere mass-division, — and their definite distribution to the daughtercells. "The essential operation of nuclear division is the sion of the mother-granules" (i.e. the individual chromatin-grains) ; "all the other phenomena are for the purpose of transporting the daughter-granules derived from the division of a mother-granule, one to the centre of one of the daughter-cells, the other to the centre of the other." In this respect the nucleus stands in marked contrast to the cytoplasm, which undergoes on the whole a mass-division, although certain of its elements, such as the plastids and the centrosome, may separately divide, like the elements of the nucleus. From this factRoux argued, first, that different regions of the nuclear substance must represent different qualities, and second, that the apparatus of mitosis is designed to distribute these qualities, according to a definite law, to the daughter-cells. The particular form in which Roux and Weismann developed this conception has now been generally rejected, and in any form it has some serious difficulties in its way.• We cannot assume a precise localization of chromatin-elements in all parts of the nucleus ; for on the one hand a large part of the chromatin may degenerate or be cast out (as in the maturation of the egg), and on the other hand in the Protozoa a small fragment of the nucleus is able to regenerate the whole. Nevertheless, the essential fact remains, as Hert wig, Kolliker, Strasburger, De Vries, and many others have insisted, that in mitotic cell-division the chromatin of the mother-cell is distributed with the most scrupulous equality to the nuclei of the daughter-cells, and that in this regard there is a most remarkable contrast between nucleus and cytoplasm. This holds true with such wonderful constancy throughout the series of living forms, from the lowest to the highest, that it must have a deep significance. And while we are not yet in a position to grasp its full meaning, this contrast points unmistakably to the conclusion that the most essential material handed on by the mother-cell to its progeny is the chromatin, and that this substance therefore has a special significance in inheritance.