Physiological Relations of Nucleus and Cytoplasm

growth and cell

These beautiful observations prove that destructive metabolism, as manifested by co-ordinated forms of protoplasmic contractility, may go on for some time undisturbed in a mass of cytoplasm deprived of a nucleus. On the other hand, the formation of new chemical or morphological products by the cytoplasm only takes place in the presence of a nucleus. These facts form a complete demonstration that the nucleus plays an essential part not only in the operations of synthetic metabolism or chemical synthesis, but also in the morphological determination of these operations, i.e. the morphological synthesis of Bernard—a point of capital importance for the theory of inheritance, as will appear beyond.

Convincing experiments of the same character and leading to the same result have been made on the unicellular plants. Klebs observed as long ago as 1879 that naked protoplasmic fragments of Vaucheria and other algae were incapable of forming a new cellulose membrane if devoid of a nucleus ; and he afterwards showed ('87) that the same is true of Zygnema and By plasmolysis the cells of these forms may be broken up into fragments, both nucleated and non-nucleated. The former surround themselves with a new wall, grow, and develop into complete plants ; the latter, while able to form starch by means of the chlorophyll they contain, are incapable of utilizing it, and are devoid of the power of forming a new membrane, and of growth and regeneration.' Although Verworn's results confirm and extend the earlier work of Nussbaum and Gruber, he has drawn from them a somewhat different conclusion, based mainly on the fact, determined by him, that a nucleus deprived of cytoplasm is as devoid of the power to regenerate the whole as an enucleated mass of cytoplasm. From this he argues, with perfect justice, that the formative energy cannot properly be ascribed to the nucleus alone, but is rather a co-ordinate activity of both nucleus and cytoplasm. No one will dispute this conclusion; yet in the light of other evidence it is, I think, stated in somewhat misleading terms which obscure the significance of Verworn's own beautiful experiments. It is undoubtedly true that the cell, like any other living organism, acts as a whole, and that the integrity of all of its parts is necessary to its continued existence ; but this no more precludes a specialization and localization of function in the cell than in the higher organism. The experiments certainly do not prove that the nucleus is the sole instrument of organic synthesis, but they no less certainly indicate its especial importance in this process. The sperm-nucleus is unable to develop its latent capacities without becoming associated with the cytoplasm of an ovum, but its significance as the bearer of the paternal heritage is not thereby lessened one iota.

Position and Movements of the Nucleus

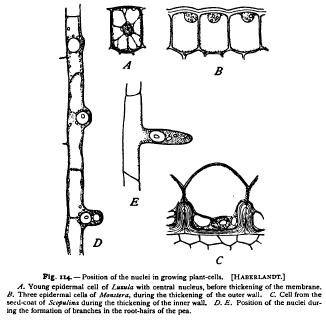

Many observers have approached the same problem from a different direction by considering the position, movements, and changes of form in the nucleus with regard to the formative activities in the cytoplasm. To review these researches in full would be impossible, and we must be content to consider only the well-known researches of Haberlandt ('77) and Korschelt ('89), both of whom have given extensive reviews of the entire subject in this regard. Haberlandt's studies related to the position of the nucleus in plantcells with especial regard to the growth of the cellulose membrane. He determined the very significant fact that local growth of the cell-wall is always preceded by a movement of the nucleus to the point of growth. Thus, in the formation of epidermal cells the nucleus lies at first near the centre, but as the outer wall thickens, the nucleus moves towards it, and remains closely applied to it throughout its growth, after which the nucleus often moves into another part of the cell (Fig. 114, A, B). That this is not due simply to a movement of the nucleus towards the air and light is beautifully shown in the coats of certain seeds, where the nucleus moves not to the outer, but to the inner wall of the cell, and here the thickening takes place (Fig. t 14, C). The same position of thenucleus is shown in the thickening of the walls of the guard-cells of stomata, in the formation of the peristome of mosses, and in many other cases. In the formation of root-hairs in the pea, the primary outgrowth always takes place from the immediate neighbourhood of the nucleus, which is carried outward and remains near the tip of the growing hair (Fig. I14, D, E). The same is true of the rhizoids of fern-prothallia and liverworts. In the hairs of aerial plants this rule is reversed, the nucleus lying near the base of the hair ; but this apparent exception proves the rule, for both Hunter and Haberlandt show that in this case growth of the hair is not apical, but proceeds from the base ! Very interesting is Haberlandt's observation that in the regeneration of fragments of Vaucheria the growing region, where a new membrane is formed, contains no chlorophyll, but numerous nuclei. The general result, based on the study of a large number of cases, is in Haberlandt's words that " the nucleus is in most cases placed in the neighbourhood, more or less immediate, of the points at which growth is most active and continues longest." This fact points to the conclusion that " its function is especially connected with the developmental processes of the and that " in the growth of the cell, more especially in the growth of the cell-wall, the nucleus plays a definite part." Korschelt's work deals especially with the correlation between form and position of the nucleus and the nutrition of the cell; and since it bears more directly on chemical than on morphological synthesis, may be only briefly reviewed at this point. His general conclusion is that there is a definite correlation, on the one hand between the position of the nucleus and the source of food-supply, on the other hand between the size of the nucleus and the extent of its surface and the elaboration of material by the cell. In support of the latter conclusion many cases are brought forward of secreting cells in which the nucleus is of enormous size and has a complex branching form. Such nuclei occur, for example, in the silk-glands of various lepidopterous larvae (Meckel, Zaddach, etc.), which are characterized by an intense secretory activity concentrated into a very short period. Here the nucleus forms a labyrinthine network (Fig. 11, E), by which its surface is brought to a maximum, pointing to an active exchange of material between nucleus and cytoplasm. The same type of nucleus occurs in the Malpighian tubules of insects (Leydig, R. Hertwig), in the spinningglands of amphipods (Mayer), and especially in the nutritive cells of the insect ovary already referred to at p. 114. Here the developing ovum is accompanied and surrounded by cells, which there is good reason to believe are concerned with the elaboration of food for the egg-cell. In the earwig Forficula each egg is accompanied by a single large nutritive cell (Fig. 115), which has a very large nucleus rich in chromatin (Korschelt). This cell increases in size as the ovum grows, and its nucleus assumes the complex branching form shown in the figure. In the butterfly Vanessa there is a group of such cells at one pole of the egg from which the latter is believed to draw its nutriment (Fig. 58). A very interesting case is that of the annelid referred to at p. 114. Here, as described by Korschelt, the egg floats in the perivisceral fluid, accompanied by a nurse-cell having a very large chromatic nucleus, while that of the egg is smaller and poorer in chromatin. As the egg completes its growth, the nursecell dwindles away and finally perishes (Fig. 57). In all these cases it is scarcely possible to doubt that the egg is in a measure relieved of the task of elaborating cytoplasmic products by the nurse-cell, and that the great development of the nucleus in the latter is correlated with this function.