Lamp

shade, vase, curves, bottom, simple, line, proportions, fig and base

Proportion.

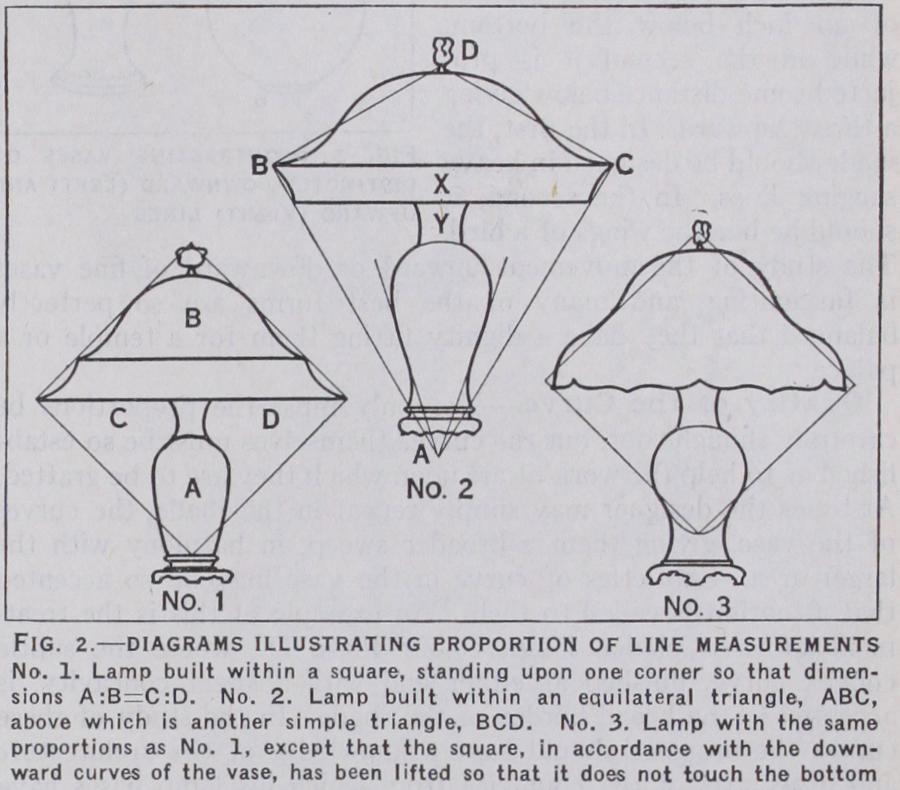

In designing a lamp-shade the proportions must be so simple that the eye can measure them and take pleasure in them. Often a lamp can be built within a square standing upon one corner (fig. 2, No. I), which gives an interesting simple pro portion between the ratios of the height of the vase and the height of the shade, and what may be termed the two wings of the shade divided by the centre line of the symmetrical form. Thus dimensions A:B=C:D. Other arrangements may be used. In fig. 2, No. 3, the same proportions have been used, except that the square has been lifted so that the lower point does not touch the bottom of the vase. In fig. 2, No. 2, a different arrangement has been adopted. The focal point of the base in this case was felt by the artist to be a short distance below the actual base. By erecting from this point A two lines at an angle of 6o° from the horizontal and connecting them with the line B–C, the height of which was established at a distance above the mouth of the vase equal to the distance between the top of the shoulder of the vase and its mouth, an equilateral triangle was formed, above which was erected another simple triangle with base angles of 3o°. The distance from the apex of this triangle to the shoulder of the vase is equal to the radius of the shade. Thus there is no limitation other than that of the use of simple proportions based upon simple geometric forms.

Aside from the proportions of line, we should consider the pro portions of area of front elevation which may be built upon any simple ratio. Thus, most of the shades shown in the colour plates are twice the size of the vases, while the one in the lower right hand corner of Plate II. is three times the size. This ratio is ob vious in the square lines of the Ming lamp in the upper right hand corner of Plate I. The shade appears in the same area as would two of the vases set side by side. Any of these simple proportions may be used, creating a feeling of satisfaction and architectural structure. (See DRAWING.) At times the point to be selected from which to work is not at the exact bottom of the vase. The establishment of this starting point depends on the curves of the vase as they approach the bottom. It will be seen that these curves in fig. 2, No. 2 sweep in a downward direction more strongly than do those in fig. 2, No. 3. In the first vase the curves of the shoulders drop into straight lines which establish point A. The other vase with an egg-shaped body establishes this point well above the bottom at the point of the egg or the convergence of the more rounded curves. In fig. 3 will be seen two contrasting vases, one a bottle shape with a distinctly downward movement because the weight of the body is so low that it seems to sag, while the other seems to stand on tip-toe. In the first, the

position of the base is fixed by the rounded curves at a fraction of an inch below the bottom, while in the second it is pro jected some distance below giving a thrust upward. In the first, the shade should be designed in heavy sagging lines. In the second, it should be like the wings of a bird.

The study of the movement upward or downward of fine vases is fascinating, and many of the best forms are so perfectly balanced that they have a dignity fitting them for a temple or a palace.

Quality of the Curve.

Not only must the proportions be carefully thought out, but the curves themselves must be so estab lished as to help the work of art upon which they are to be grafted. At times the designer may simply repeat in the shade, the curves of the vase, giving them a broader sweep, in harmony with the larger area. Subtleties of curve in the vase may be so accented that attention is called to them. An example of this is the treat ment of the Celadon lamp, colour Plate II., where the subtle convex curve, finished at either end with a slight concavity, is accented in the broad border of the shade. In the study of these curves the designer should have a knowledge of the architecture and other arts of the countries from which his lamp bases have been selected. There is a prim puritanical quality in Chinese art up to the Ming dynasty, which is never duplicated in the softer, rounder curves of the art of the Near East. These characteristics should be accented rather than contradicted.

In the treatment of the necessarily strong horizontal line at the bottom of the shade the sensitive artist feels, if he has studied the curves of the vase and followed them up to its mouth, that there is a too abrupt stop before arriving at the curves of the shade. That many designers have felt this is shown by the tendency to attempt to soften this line with fringe or some other decorative treatment. Fringe is bad, as there are very few vases, even includ ing those of the Italian Renaissance, which could be associated with textiles so finished. The architectural severity of the base, be it pottery, bronze or wood, demands that the shade be treated more or less architecturally, but that this line may be softened by the design alone, will be seen in the two lamps at the bottom of colour Plate II. The softening is accomplished by curving the wires which drop into the bottom circumference of the shade, and sometimes by treating the line itself in various scalloped forms, as may be seen in flowers with rounded or pointed petals; and though the designer of a vase seldom uses petals, because they are too easily broken, the designer of the shade may use them, as they do not weaken the shade.