Lamp

lamps, bronze, handle, oil, employed, nozzles, torch, lantern and bc

LAMP, the general term for an apparatus in which some com bustible substance, generally for illuminating purposes, is held. Lamps are usually associated with lighting, though the term is also employed in connection with heating (e.g., spirit-lamp) ; and as now employed for oil, gas and electric light they are dealt with in the article on LIGHTING. From the artistic point of view, in modern times, their variety precludes detailed reference here ; but their archaeological history deserves a fuller account.

Though Athenaeus states (xv. 70o) that the lamp was not an ancient invention in Greece, it had come into general use there for domestic purposes by the 4th century B.C., and no doubt had long before been employed for temples or other places where a per manent light was required in place of the torch of Homeric times. Herodotus (ii. 62) sees nothing strange in the "festival of lamps," Luchnokaie, which was held at Sais in Egypt, except in the vast number of them. Each was filled with oil so as to burn the whole night. Again he speaks of evening as the time of lamps (vii. 215).

Still, the scarcity of lamps in a style anything like that of an early period, compared with the im mense number of them from the late Greek and Roman age, seems to justify the remark of Athen aeus. The commonest sort of domestic lamp was of terra-cotta and of the shape seen in figs. i and 2, with a spout or nozzle in which the wick burned, a round hole on the top to pour oil in and a handle with which to carry it.

Some lamps had two or more spouts and there was a large class with numerous holes for wicks but without nozzles. Decoration was confined to the front of the handle, or more commonly to the circular space on the top of the lamp, and it consisted almost always of a design in relief, taken from mythology or legend, from objects of daily life or scenes such as displays of gladiators or chariot races, from animals and the chase. A lamp in the British Museum has a view of the in terior of a Roman circus with spectators looking on at a chariot race. In other cases the lamp is made altogether of a fantastic shape, as in the form of an animal, a bull's head, or a human foot. Naturally colour was excluded from the ornamentation except in the form of a red or black glaze, which would resist the heat. The typical form of hand lamp (figs. 1, 2) is a com bination of the flatness necessary for carrying steady and re maining steady when set down, with the roundness evolved from the working in clay and characteristic of vessels in that material. In the bronze lamps this same type is retained, though the round ness was less in keeping with metal. Fanciful shapes are equally common in bronze. The standard form of handle consists of a ring for the forefinger and above it a kind of palmette for the thumb. Instead of the palmette is sometimes a crescent, no doubt

in allusion to the moon. It was only with bronze lamps that the cover protecting the flame from the wind could be used, as was the case out of doors in Athens. Such a lamp, because of this pro tection, was in fact a lantern.

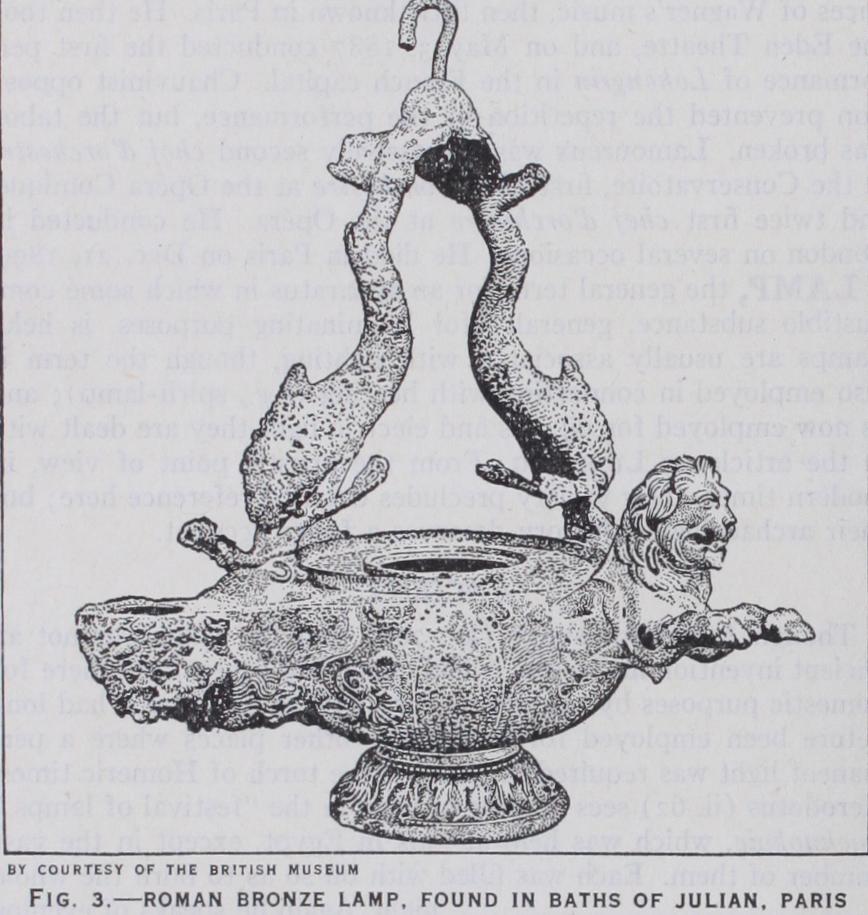

,Apparently it was to the lantern that the Greek appellation lampas, a torch, was first transferred, probably from a custom of having guards to protect the torches also. Afterwards it came to be employed for the lamp itself. When Juvenal (Sat., iii. 277) speaks of the aenea lampas he may mean a torch with a bronze handle, but more probably either a lamp or a lantern. Lamps used for suspension were mostly of bronze, and in such cases the deco ration was on the under part, so as to be seen from below. Of this the best example is the lamp at Cortona, found there in 1840 (engraved, Monumenti d. inst. arch., iii. pls. 41, 42, and in Dennis, Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria, 2nd ed. ii. p. 403). It is set round with 16 nozzles ornamented alternately with a siren and a satyr playing on a double flute. Between each pair of nozzles is a head of a river god, and on the bottom of the lamp is a large mask of Medusa, surrounded by bands of animals. These designs are in relief, and the workmanship, which appears to belong to the beginning of the 5th century B.C., justifies the esteem in which Etruscan lamps were held in antiquity (Athenaeus, xv. 70o). Of a later but still excellent style is a bronze lamp in the British Mu seum found in the baths of Julian in Paris (fig. 3). The chain is attached by means of two dolphins very artistically combined. Under the nozzles are heads of Pan; and from the sides project the foreparts of lions. To what extent lamps may have been used in temples is unknown. Probably the Erechtheum on the Acropolis of Athens was an exception in having a gold one kept burning day and night, just as this lamp itself must have been an exception in its artistic merits. It was the work of the sculptor Callimachus, and was made apparently for the newly rebuilt temple a little before 400 B.C. When once filled with oil and lit it burned continuously for a whole year. The wick was of a fine flax called Carpasian (now understood to have been a kind of cotton), which proved to be the least combustible of all flax (Pausanias, i. 26. 7). Above the lamp a palm tree of bronze rose to the roof for the purpose of carrying off the fumes. But how this was managed it is not easy to determine unless the palm be supposed to have been inverted and to have hung above . the lamp, spread out like a re flector, for which purpose the pol ished bronze would have served fairly well. The stem if left hol low would collect the fumes and carry them out through the roof.