House Decoration - Difference Between Color and Paints

yellow, complementary, green, colors, blue, red and hue

The term tone must not be confounded with brightness. The latter has reference to the quantity of sensational stimulus given to the op tic nerves by a given area of colored surface, and is measured by the amount of light reflected by the color.

Tones are estimated by the absolute amount of color sensation they excite. They may be grouped into three series for every possible hue or kind of color, according as these hues are ad mixed with white, with black, or with both black and white, or grey. Apart from any alteration of hue which may occur by such admixtures, it may be affirmed that a normal color is weakened or reduced by the addition of white, producing tones in a scale of series from deep to pale; and a normal color is made darker, but not deeper, by the addition of black.

Tones belonging to any of the above series are commonly spoken of as shades; but it is bet ter to limit the use of this term to admixtures with black. A scale is a regular series of such tones as those which have been defined above. So each hue admits of three scales : (1) The reduced scale—that is, the normal hue mixed with increasing amounts of white, thus forming tints.

(2) The darkened scale—that is, the normal hue mixed with increasing amounts of black, thus forming shades.

(3) The dulled scale—that is, the normal hue mixed with increasing amounts of grey, thus forming broken tints, commonly called greys.

There are several ways of preparing a series of tones belonging to each of the scales, assum ing that we are dealing with pure pigments, and not with colored lights. To obtain a scale of, say, ten tints of a color, add one-twentieth of zinc-white for the first tint, two-twentieths for the second, three-twentieths for the third, and so on up to half and half for the tenth tint.

Green is not, as generally supposed, a com pound color,,made up of blue and yellow. This is clearly demonstrated by projecting a disc of pure blue upon a screen, and over it another disc of pure yellow. The result is not green, but white. The explanation of the popular error is. that when ordinary impure blues and yellows are mixed, the dominant colors neutralize each other, and leave the impurities visible. These impurities invariably show up as greens. Yel

low itself is proved by lantern-slide to be capable of being made by green and red rays projected jointly on the screen.

Water and clear glass reflect scarcely any rays, while snow or powdered glass reflects nearly all. The irregularly disposed surfaces of the crystals throw off light in every direction; but as soon as a fluid medium having the same essential power of reflection is used to fill up the interstices, transparency is restored. A vessel filled with powdered glass and cold bisulphide of carbon allows only green rays to pass through; but on being warmed, only yellow rays appear.

The primary pigments, being the first simple division, consist of blues, reds, and yellows. By combining chemically suitable blue and red, we obtain purple; with red and yellow we get orange; while blue and yellow pigments com bine to give us green colors. These resultant ad mixtures of any two primaries are termed sec ondary colors; and again by a similar process of mixing, in certain proportions, two of the sec ondary pigments together, we obtain the third distinct class into which we divide our colors— known as the tertiary colors.

With the primary pigments at hand, almost every variety of color requisite or desirable for our ordinary use can be prepared.

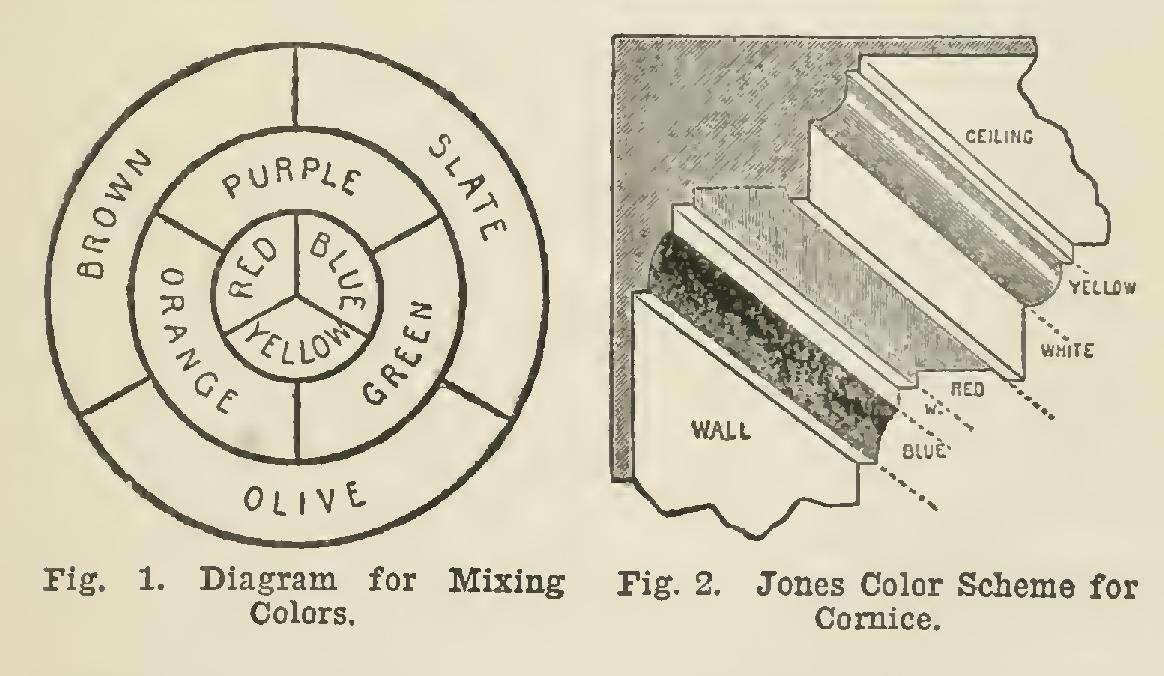

The diagram, Fig. 1, shows the complemen tary color to each primary, and the two comple mentaries to each secondary: Primaries : Red, Blue, Yellow.

Secondaries: Purple, Orange, Green. Tertiaries : Brown, Slate, Olive.

A primary color is complementary to the color• formed by mixture of the other two primaries: Red Complementary to Green. Blue complementary to Orange.

Yellow complementary to Purple.

A secondary is complementary to the color formed by mixture of the other two secondaries, and also to the primary to which it is comple mentary: Green complementary to Brown or Red. Orange complementary to Slate or Blue. Purple complementary to Olive or Yellow.

A color's pure complement is formed of equal parts of each, and in this diagram all colors are as above—though, of course, different tones can be made up by unequal proportions. Light being the source of color, it can only be divided into its components.