Roofs and Roof Construction

beam, tie, fig, rafters, shown, truss, feet and piece

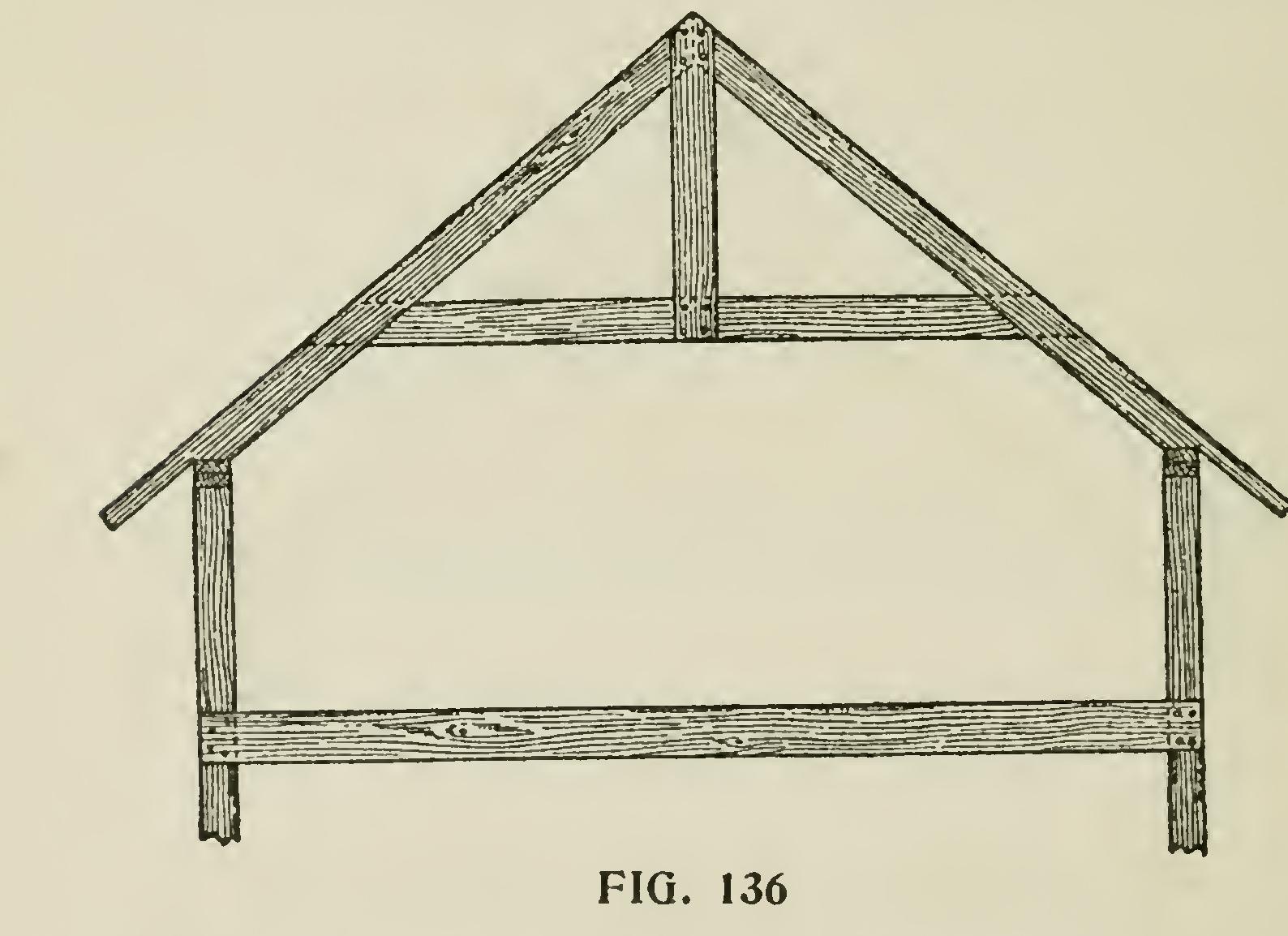

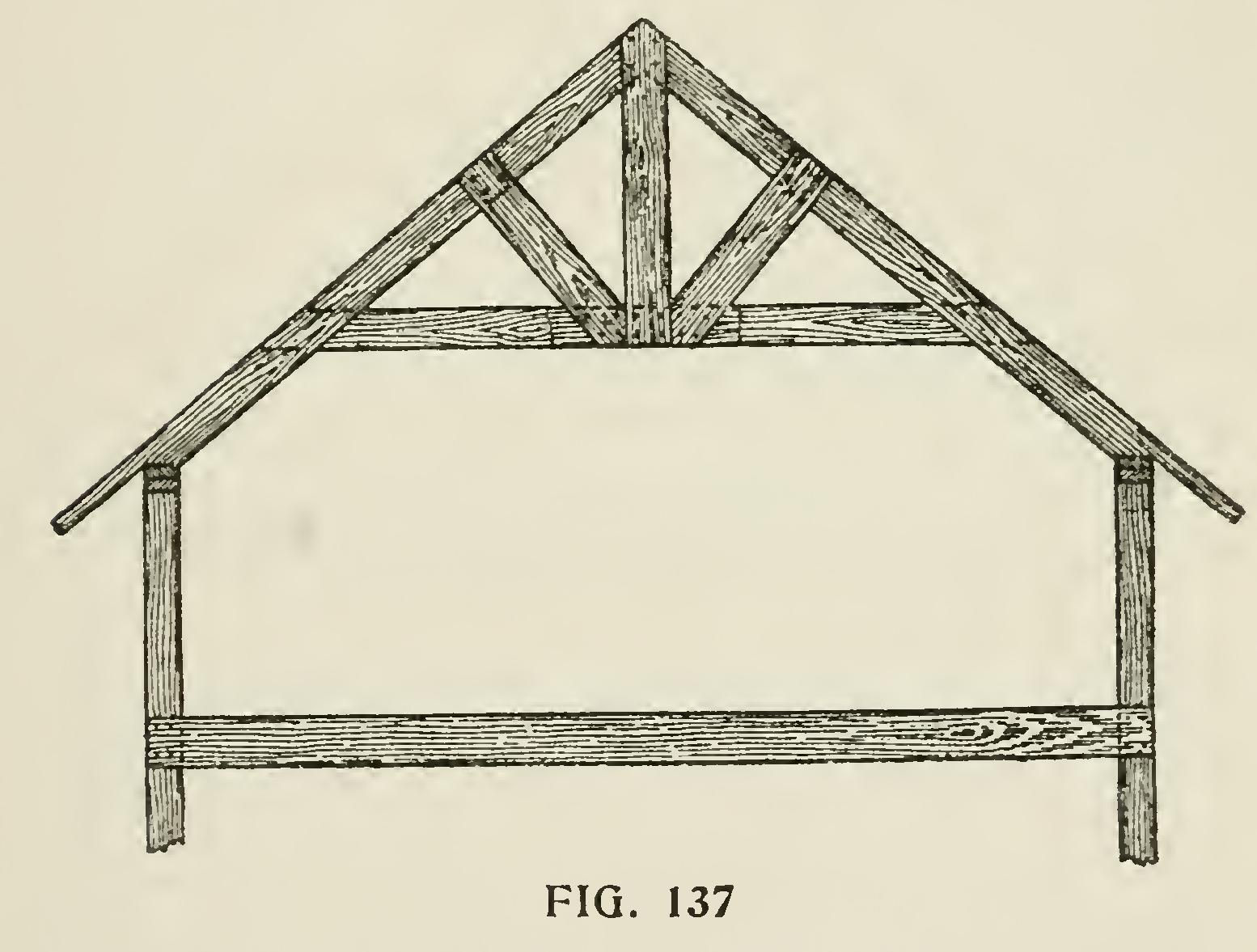

The most simple form of truss is that shown in Fig. 134, and is called the common rafter—so named, we presume, because it is used in all classes of building. When it becomes necessary to add to its strength, the first thing done is to nail on a cross piece, as shown in Fig. 135, com monly called a tie or collar beam. This piece also serves as the ceiling joist where it is desired to finish a room in the attic. Some times a vertical piece is added at the center, as shown in Fig. 136. This, of course, stiffens the truss, but it does not add as much to its strength as is generally sup posed. This is a common form used for one and a half story houses. The cross piece has a double purpose here ; that it, to keep the side walls from spreading outwards and also forms the ceiling. It can be greatly strengthened by the addition of two extra pieces set brace shape from the center of the collar beam, as shown in Fig. 137. The lower the collar beam is placed the stronger will be the truss, and should not in most cases be placed above one-third the length of the common rafter.

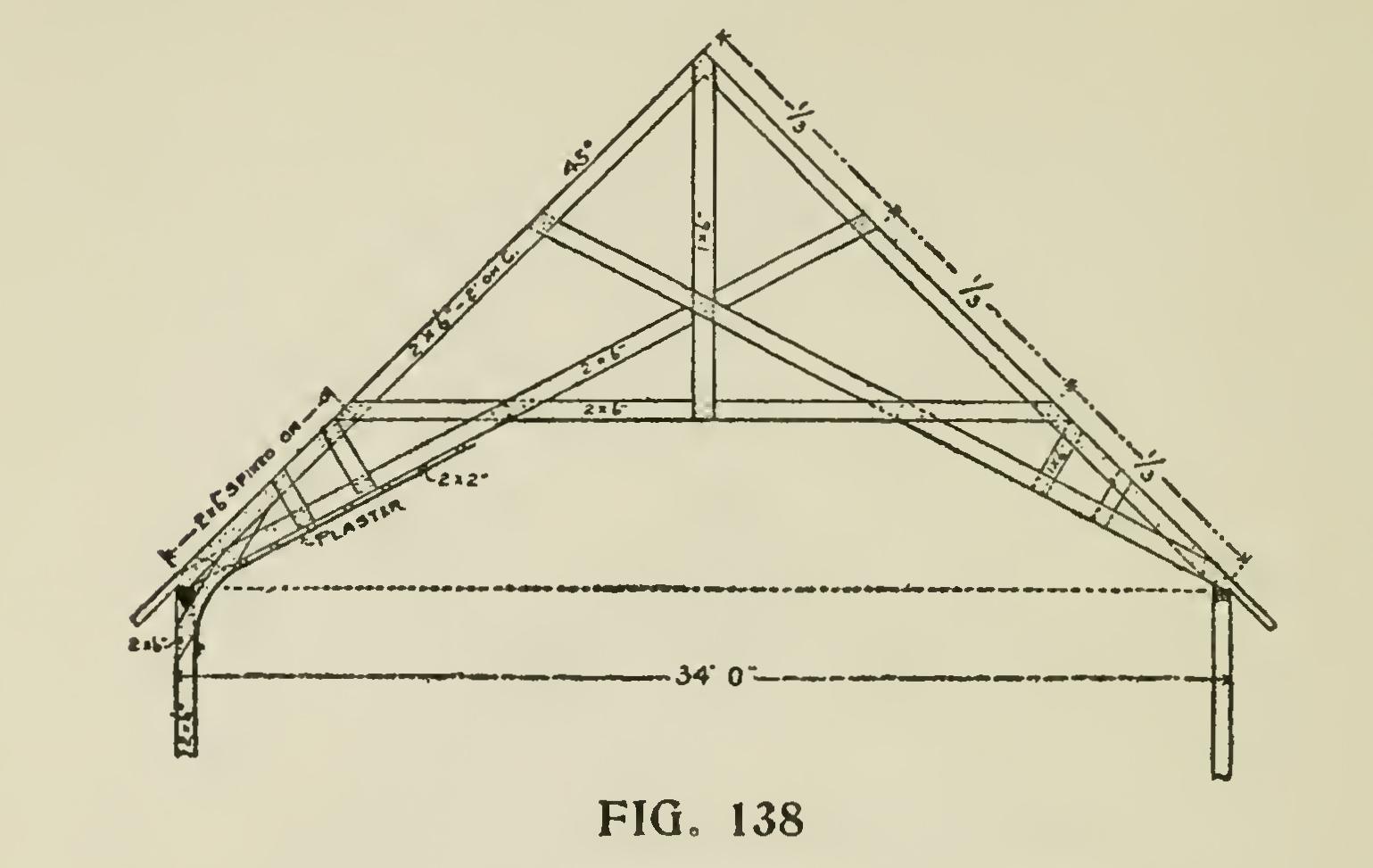

Another form of truss that is generally used for small church buildings is that shown in Fig.

138, commonly called scissors truss. This is suitable for a building 34 feet wide, shingle roof, and rafters set on 24-inch centers. The timbers required will be 26 feet in length for the common tie rafters and 24 feet for the collar beam. At the seat of the rafters is a 2 by 6-inch piece circled out to form a cove, as shown. This piece should be thoroughly spiked to the studding and to the side of the tie rafter and to the under edge of the common rafter. However, only one-third of these pieces will catch the rafters, owing to their being spaced on 24-inch centers, thus requir ing the other pieces to be framed in between the rafters. Other timbers in the truss are 1 by 6 inch fencing plank. All parts should be thoroughly spiked together. Cross pieces of 2 by 2-inch stuff are used to receive the lath and plaster.

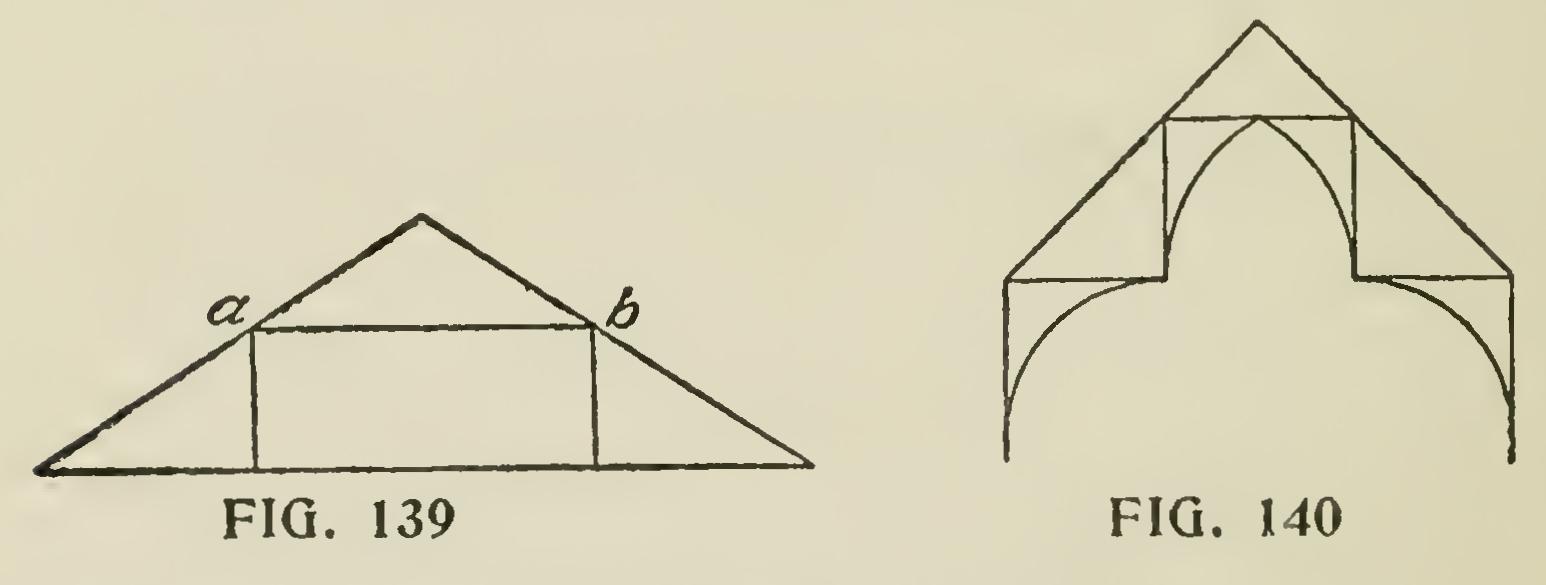

It is sometimes, however, inconvenient to have the center of the space occupied by the king post, especially where it is necessary to have apartments in the roof. In such a case recourse is had to a different manner of trussing. Two suspending posts are used, and a fourth element is introduced; namely, the straining beam a. b (Fig. 139), extending between the posts. The principle of trussing is the same. The rafters are compressed, and the tie beam and posts, the latter now called queen posts, are in a state of tension.

In some roofs, for the sake of effect, the tie beam does not stretch across between the feet of the principals, but is interrupted. In point of fact, although occupying the place of, it does not fill the office of a tie beam, but acts merely as a bracket attached to the wall (Fig. 140). It is then called a hammer beam.

The Principles of Roofs may, therefore, in respect to their construction, be divided broadly into two classes : First, those with tie beams; and second, those without tie beams.

The first class, those with tie beams, may be further classified as king post roofs and queen post roofs.

The second class may be arranged as follows: 1st. Hammer beam roofs.

2d. Curved principal roofs.

Having now given such hints regarding the principles of roof construction as will enable the workman to build any ordinary roof intelligently, we proceed to describe the methods of construc tion.

King=Post Roofs.—This form of roof is practi cally the beginning of all trusses, which are com plete framings in themselves, spanning from wall to wall, and doing duty for the cross walls, in that they support, in their turn, the ridge and purlins which require a bearing every eight or ten feet. Trusses should be no more than eight or nine feet apart and have a nine-inch bearing on eachwall.

Fig. 141 represents a king-post roof truss. P R is the principal rafter, 5 inches deep and 4 inches thick ; T the tie beams 9 by 4 inches ; S the struts, 4 by 4 inches ;and the king-post K, is 7 by 4 inches ;the cuts to give a bearing for the struts are also shown.

Flat=Pitched Roofs

are not so strong as those that are pitched higher. The nearer to the per pendicular that wood is fixed the stronger it is. This is shown by the fact that the horizontal thrust of a pair of rafters is proportionate to the length of the oblique line drawn, at right angles from the foot of the rafters, to the perpendicular dropped from the apex.

The joints of a king-post truss, in fact, all consist of mortises and tenons entering but a short distance into the timbers ; and they have all beveled shoulders which ought, wherever possible, to be at right angles to the incline of the roof.

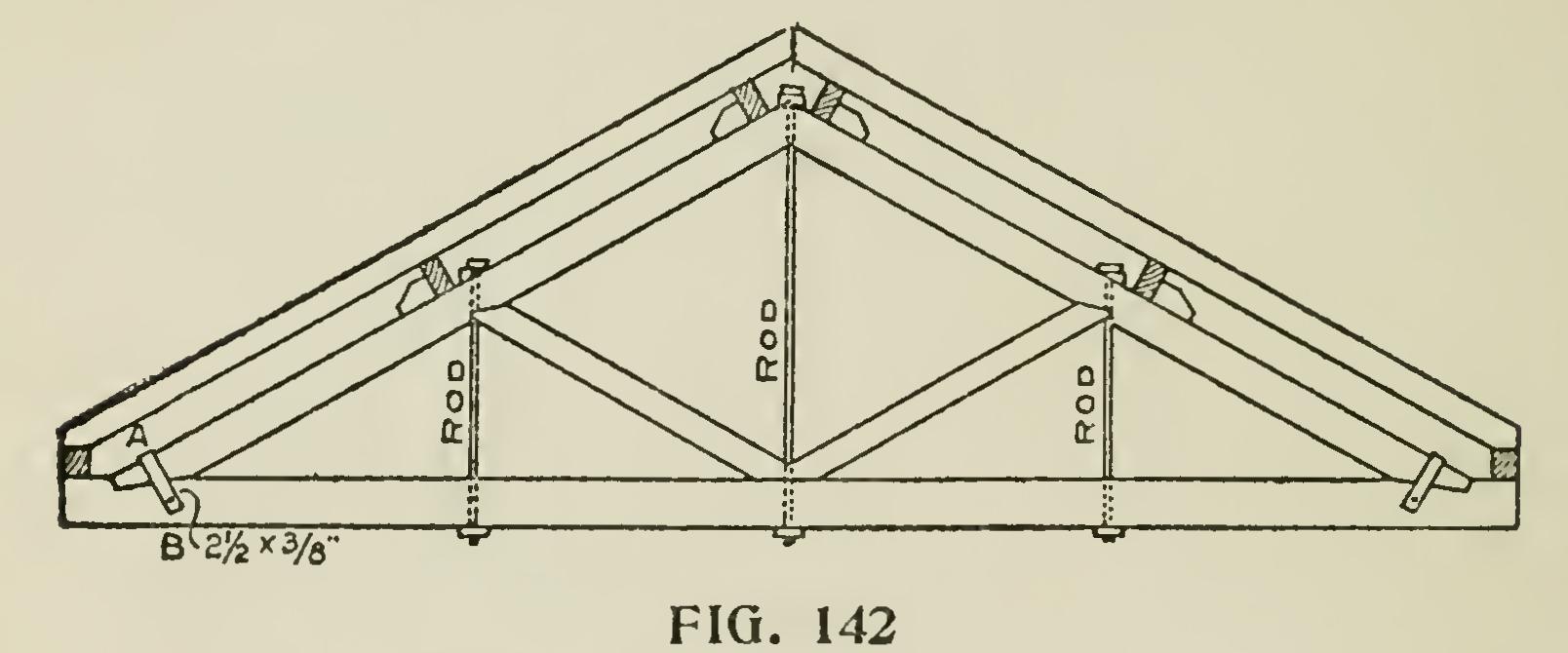

Fig. 142 is the joint between king-post and prin cipal rafters at the apex supporting the ridge, a pair of 21 by finch wrought iron straps, bolted from side to side, completing the joint; or, in practice, a through-bolt from A to B will answer the same purpose though not so good. King-post trusses are suitable for spans up to thirty feet..