Roofs and Roof Construction

tie, ac, fixed, rafters, ab and extension

ROOFS AND ROOF CONSTRUCTION It is scarcely necessary to say that the roof of a building is that covering which is to pro tect the inhabitants and their property from the effects of the weather, and that, in addition to this, it should be so constructed that it may shelter the walls, foundation and fabric gen erally from snow and rain.

Kinds of Roofs The importance of having a roof strong, water-tight, weather-proof, and durable, goes without saying. There is no other part of a building upon which greater care should be expended, to see not only that the proper kind of material is selected, but that every detail of construction is properly carried out; for upon the roof will depend, in a large measure, the health, comfort, and convenience of the occu pants and the life itself of the structure.

Roofs are of various forms and pitches; the high-pitched roofs are more generally found through the North, as they discharge the rain and snow with greater facility. When con structed on sound principles, the roof is one of the principal ties of the building, while a badly designed roof tends to force the walls out of the perpendicular.

The most simple form of roof is that known as the lean=to or shed roof. This is illustrated in Fig. 131, and it derives its name from the fact that it is the roof usually used on a small annex or shed built against or leaning against the main building.

The roof most in use and also very simple in its construction is the saddle roof or gable roof, as it is often called.

This is illustrated in Fig. 132, and shows that the roof has a double slope, and the highest point where they meet is called the ridge of the roof. Before going into the detailed construction of roofs, it will not be out of place to explain some of the principles involved in roof construction.

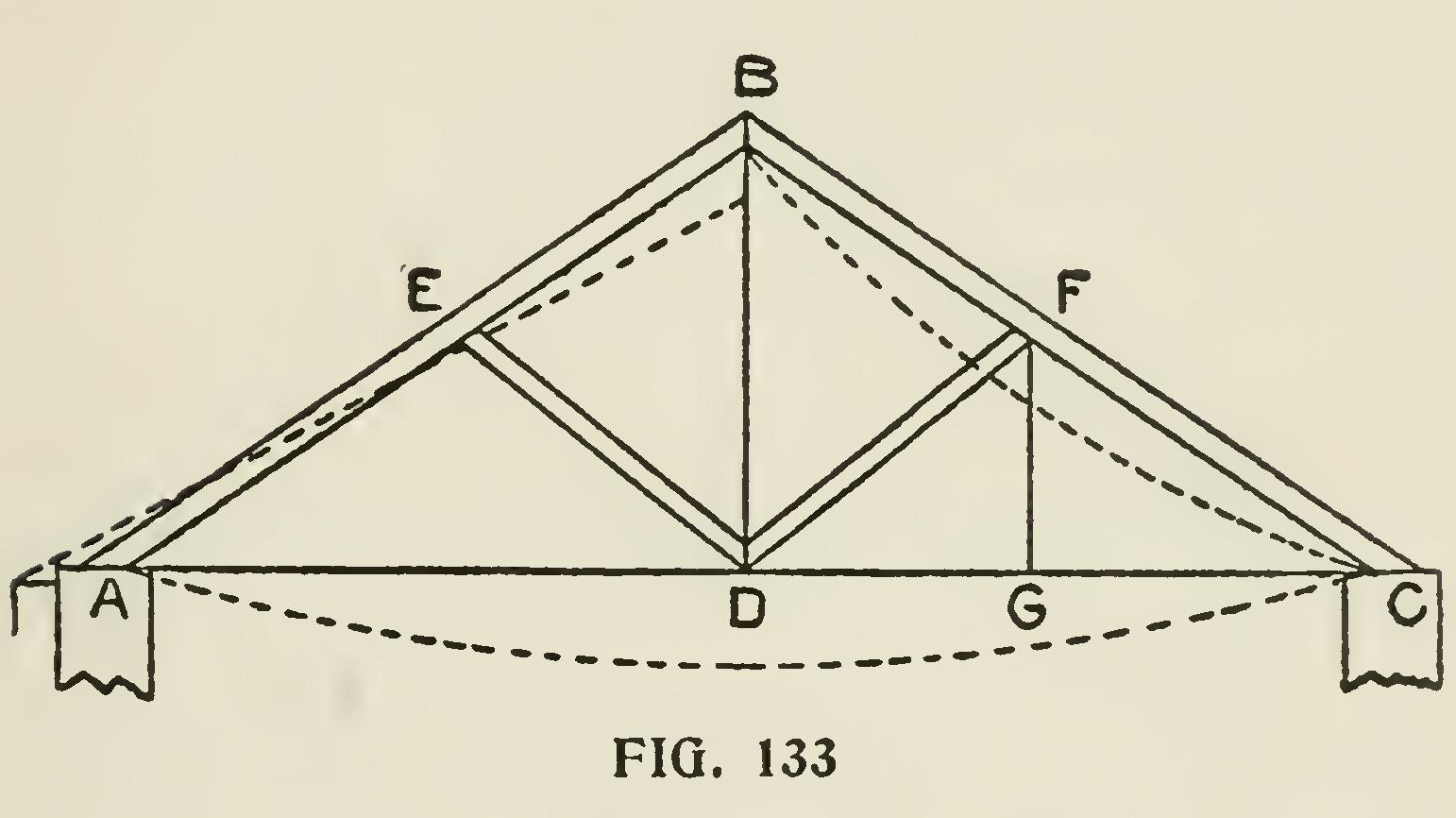

In Fig. 133, if AB, CB be two rafters, placed on walls A and C, and meeting in a ridge B, even by their own weight, and much more when loaded, these rafters would have a tendency to spread outwards at A and C, and to sink at B. If this tendency be constrained by a tie established betwixt A and C, and if AB, BC be perfectly rigid and the tie AC incapable of extension, B will become a fixed point. This, then, is the ordinary

couple roof, in which the tie AC is a third piece of timber, and which may be used for spans of limited extent; but when the span is so great that the tie AC tends to bend downward or sag, by reason of its length, then the conditions of sta bility obviously become impaired. Now, if from the point B a string or tie be let down and at tached to the middle D, of AC, it will evidently be impossible for AC to bend downwards so long as AB, BC remain of the same length : D, there fore, like B, will become a fixed point, if the tie BD be incapable of extension. But the span may be increased or the size of the rafters AB, CB be diminished, until the latter also have a tendency to sag; and to prevent this, pieces DE, DF remain unaltered in length. Adopting the ordinary meaning of the verb "to truss," as expressing to tie up, we truss or tie up the point D, and the frame ABC is a trussed frame. In like manner, F being established as a fixed point, G is trussed to it.

In every trussed frame there must obviously be one series of component parts in a state of compression and the other in a state of extension. The functions of the former can only be filled by pieces which are rigid, while the place of the latter may be supplied by strings. In the diagram the pieces AB, BC are compressed, and AC, DB are extended; yet in general the tie DB is called a king post, a term which conveys an altogether wrong idea of its duties. Thus we see how the two principal rafters, by their being incapable of compression, and the tie beam by its being in capable of extension, serve, through the means of the king post, to establish a fixed point in the center of the void spanned by the roof, which pre vents the rafters from bending, and serve in the establishing of other fixed points; and a combi nation of these pieces is called a king post roof.