Concrete Arch Bridges

arch-ring, bridge, walls, abutments, springing and built

CONCRETE ARCH BRIDGES An arch-ring carries the loads which come upon it, by means of its strength in compression, and the resistance of the abutments upon which it exerts its thrust. For this reason, any mate rial with sufficient compressive strength may be used to construct an arch. Stone masonry has served the purpose for centuries, but concrete has come to take its place. When reinforced with embedded steel, concrete arches can be built of daring spans, with thin rings and low crowns; the steel gives the arch a certain amount of flexibility which enables it to adjust itself to moving loads, settlement, temperature changes, and other conditions that might rupture an unreinforced arch.

The theory of the internal stresses in an arch-ring and the design of arch bridges are extremely difficult and involved; the highest engineering skill has been required to master the subject, and mathematicians have never ceased to wrestle with it. This, however, is not as serious as it might seem; many of the difficulties are due to the fact that the problem is really indeterminate and many refined meth ods are unnecessary. Arch-rings have a way of adjusting themselves to take their burden as di rect compression; and, if the proper precautions are taken to make the abutments absolutely unyielding, the arch-ring may be designed, as far as its thickness and general outline are con cerned, by empirical rules based on the expe rience gained from past achievements. The details of the design and reinforcement of con crete arch-rings are to be found in a number of standard works; but a study of actual structures which have recently been built will give the most practical results.

The arch-ring is only a part, important as it is, of the complete arch bridge; and the main difference in the various types of arch bridges is in the design of the superstructure.

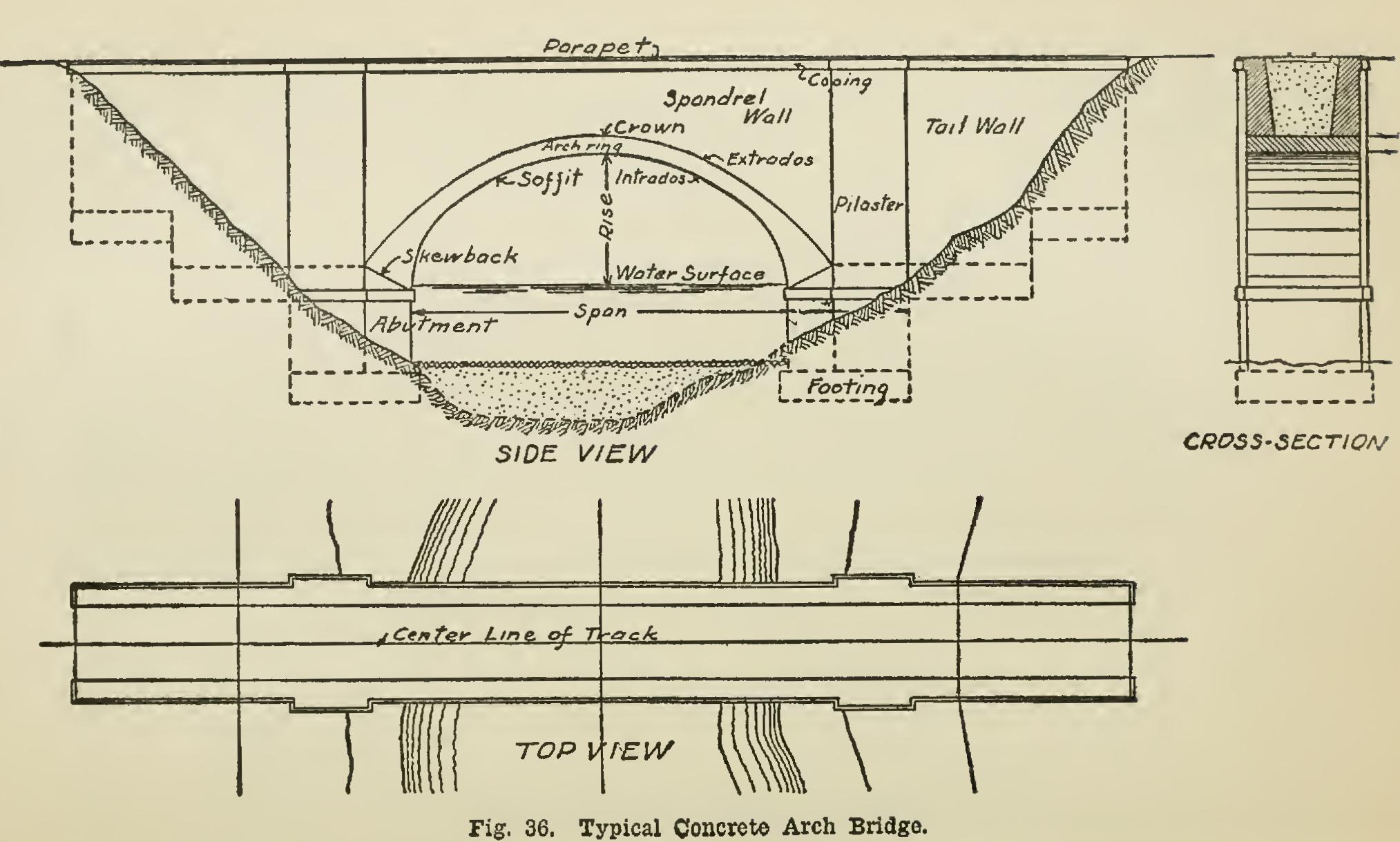

Before proceeding to the description of ex amples of the various classes and types, it would be well to define the technical terms relating to arch bridges and their details.

Definitions of Terms Arch-Barrel—The name given to the arch proper, when referred to as having length in a direction parallel to its axis.

Arch-Ring—The outline of a vertical cross-section of the arch-barrel perpendicular to the axis.

Soffit—The under surface of the arch-barrel. Intrados—The lower or inner curve of the arch-ring. Extrados—The upper or outer curve of the arch ring.

Springing or Springing Line—The intersection of the soffit with the face of the abutment; the point or line where the curvature of the intrados or soffit begins.

Crown—The highest point of the arch-ring.

Skewbacks—The inclined bearing on the abutments, upon which the arch-ring rests.

Haunches—That part of the extrados directly above the skewbacks.

Span—The horizontal distance between springings. Rise—The vertical distance from the level of the springing to the intrados at the crown.

Spandrels—A general term designating the space between the arch-ring and the top of the bridge.

Spandrel Walls—The walls resting on the arch-bar rel and supporting the bridge floor or parapet.

Parapets—The walls or tops of walls forming the sides of the bridge floors; also low spandrel walls.

Tail Walls—The continuation of the spandrel walls behind the arch abutments.

Fig. 36 is a view of a common type of arch bridge, and shows the parts defined above.

The first application of concrete to bridge work was probably in the construction of arches, which are essentially masonry structures. The first arches in the United States seem to be the two 25-ft. spans carrying Pine Road across Pennypack Creek in Philadelphia, Pa. This bridge was designed and built by Mr. C. A. Frik, superintendent of bridges for the city in 1893. Although this is a non-reinforced struc ture, 1l/2-in. wire mesh nets were placed about 2 ft. apart, horizontally and vertically, appar ently with no fixed idea of their function in caring for stresses, but merely in an effort to strengthen the work.