Possibilities of the Steel Square

circle, polygon, miter, shown, lines, polygons and triangle

POSSIBILITIES OF THE STEEL SQUARE It is doubtful if even carpenters themselves generally recognize what a wide range of possi bilities lie in the steel square. This instrument may truthfully be said to be the one great tool of the carpenter. The cutting edge, or knife, may be older; but no other tool is of greater value or capable of wider application.

What may not be accomplished with the aid of the steel square in the construction of useful and ornamental diagrams, would indeed be a hard question to answer. It is safe to say that there can be no tool devised that will ever super sede the steel square in covering so wide a range in the various construction arts. It is all con tained in the simple scale of measure in connec tion with the 90 degrees formed by the arms of the steel square, ready to solve the most intricate problems when knowingly handled by the operator.

In presenting these illustrations, it is our aim to put them in such a way that the reader will readily understand the principles involved, so that they may be intelligently reproduced, and thereby assist in opening up the way for much useful information.

Polygon Family Circle.

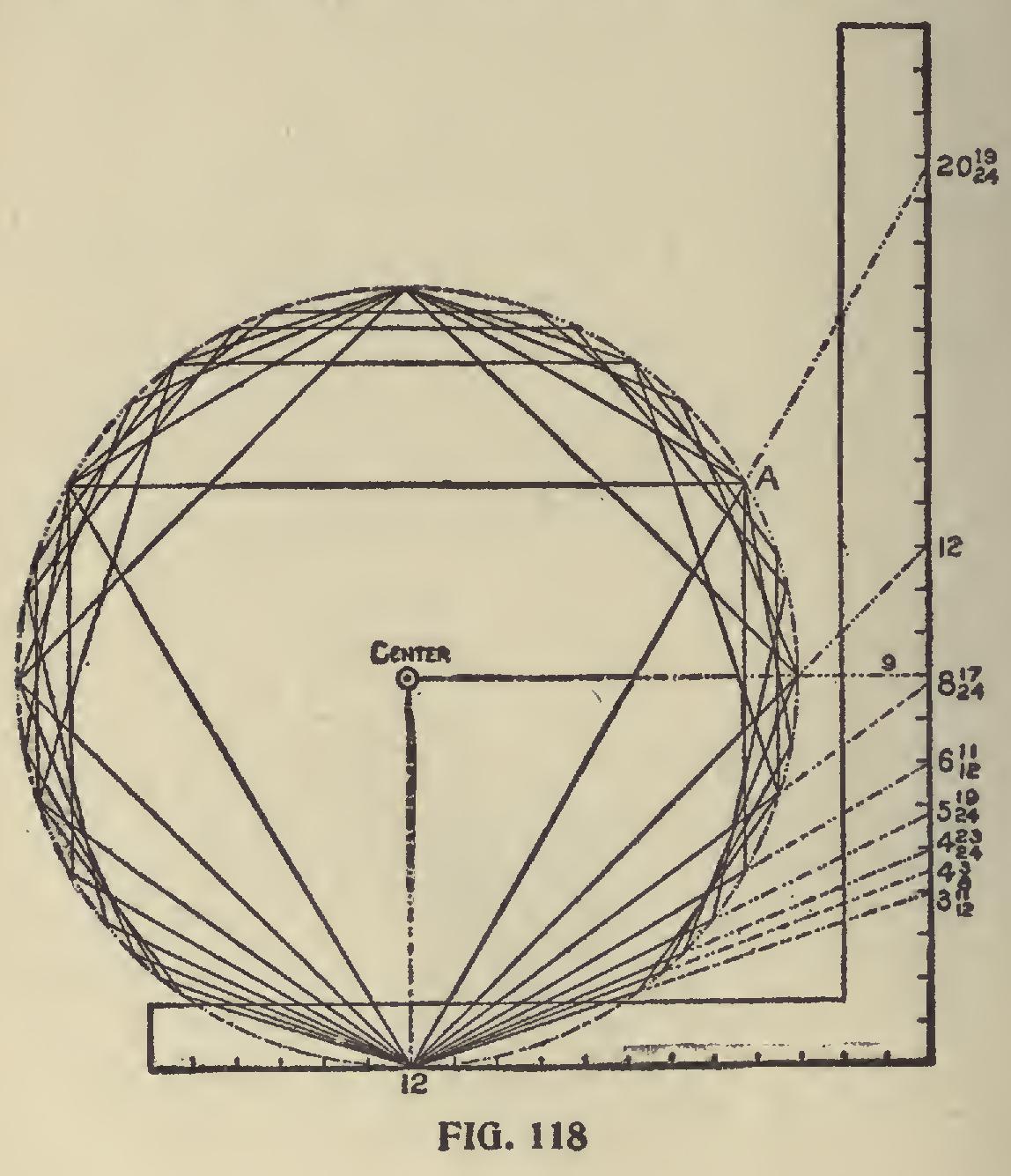

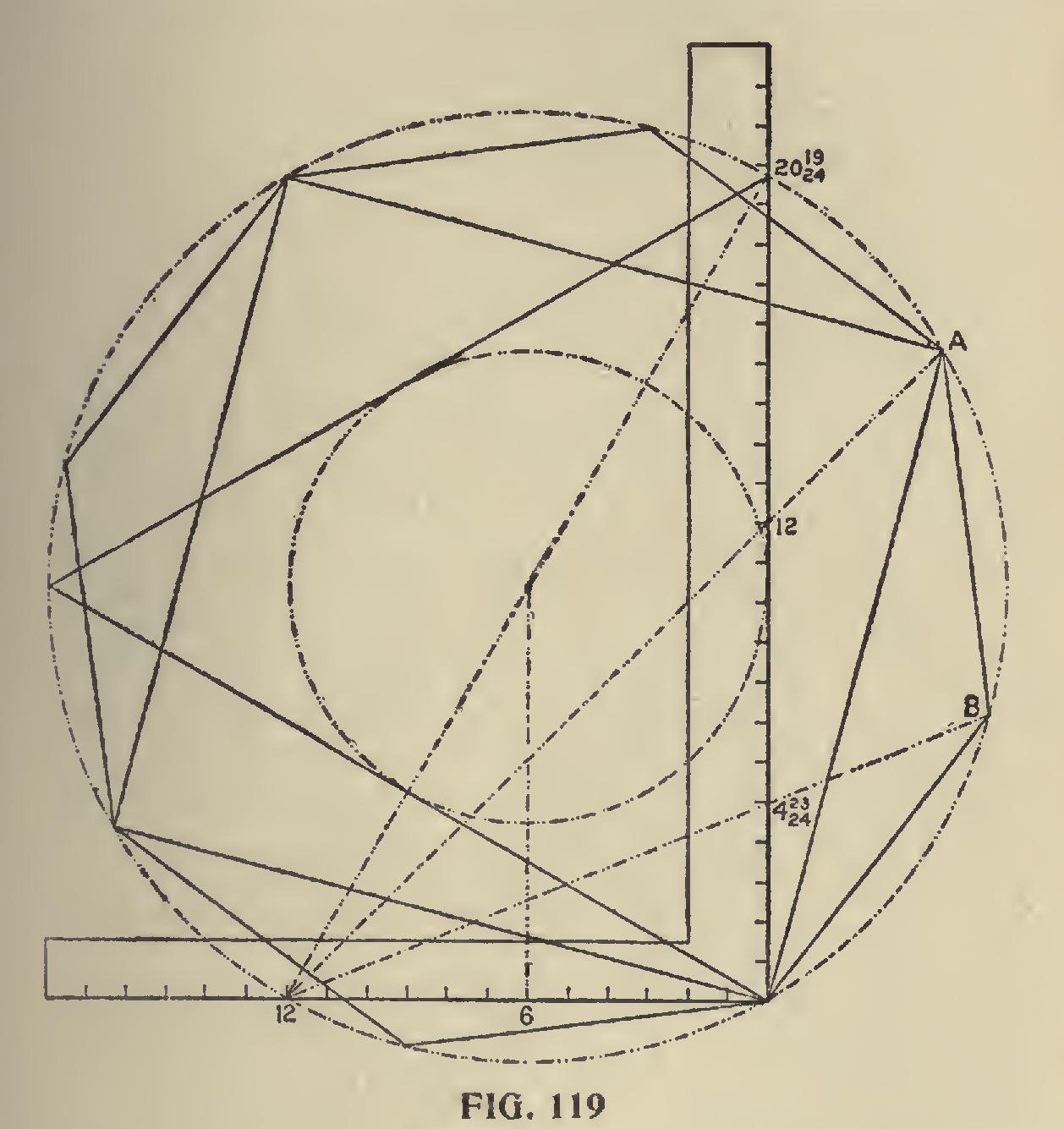

In Fig. 118 is shown the polygon family circle. In this, we show eight of the polygons enclosed in a circle, the center of which may be at a point anywhere on a perpendicular line above twelve on the tongue of the steel square. In this case it is taken at nine inches above, thereby giving a circle of eighteen inches in diameter. Where the circle cuts the miter lines, as from 12 to A of the triangle, will be the length of one of the sides and from which the others may be spaced. The reader will notice this, that a corner of each polygon is resting at 12 on the tongue, while in the next illustration, as shown in Fig. 119, they are, so to speak, run down at the heel. In this illustration only the triangle, square and octagon are shown and are enclosed in the circumscribed diameter of the triangle with an inscribed diame ter of one foot. In this the lengths of the sides of the polygons are determined from the heel of the steel square to the intersection of the miter lines with the circle as from the heel to A and B for the square and octagon respectively.

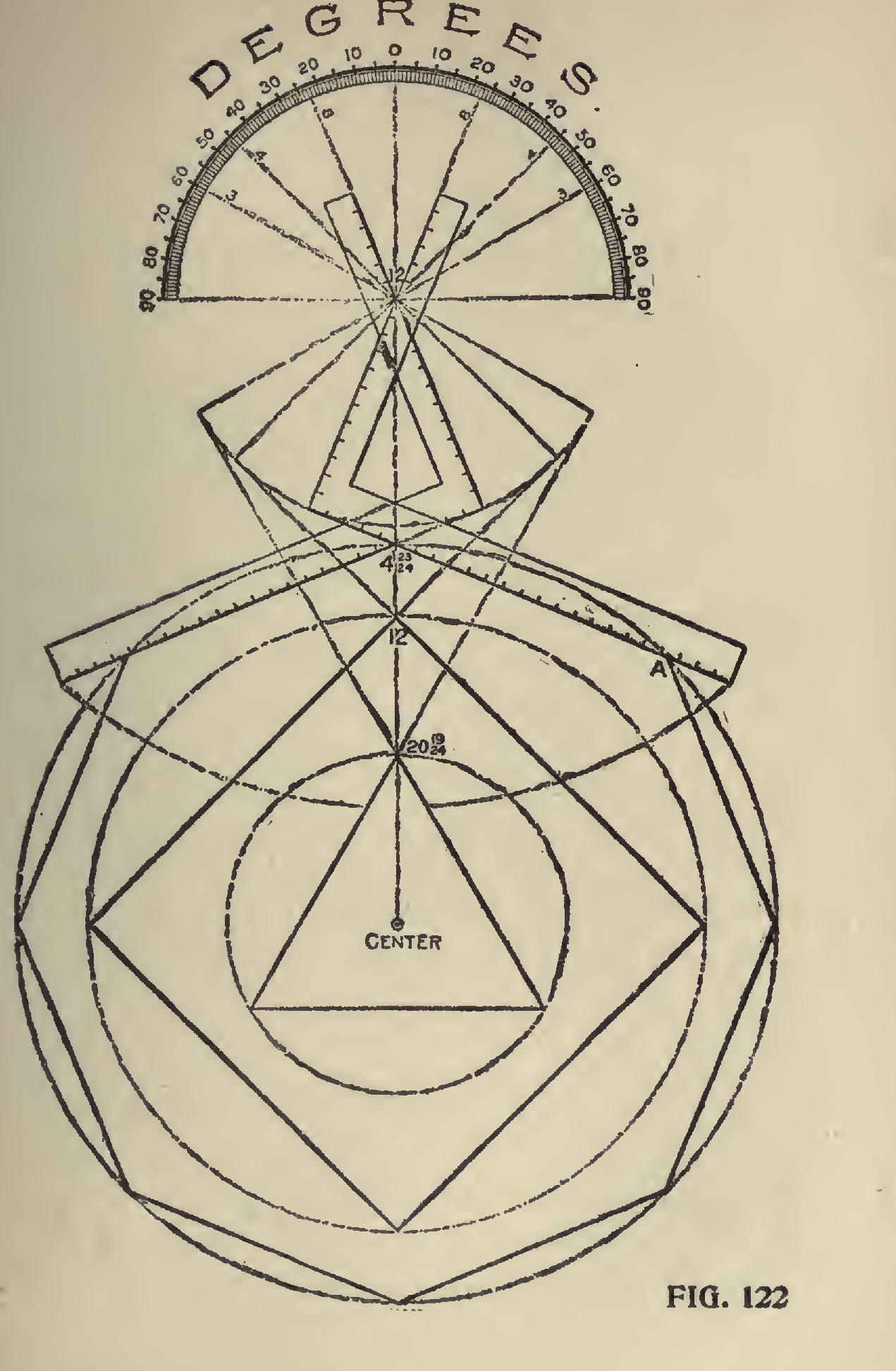

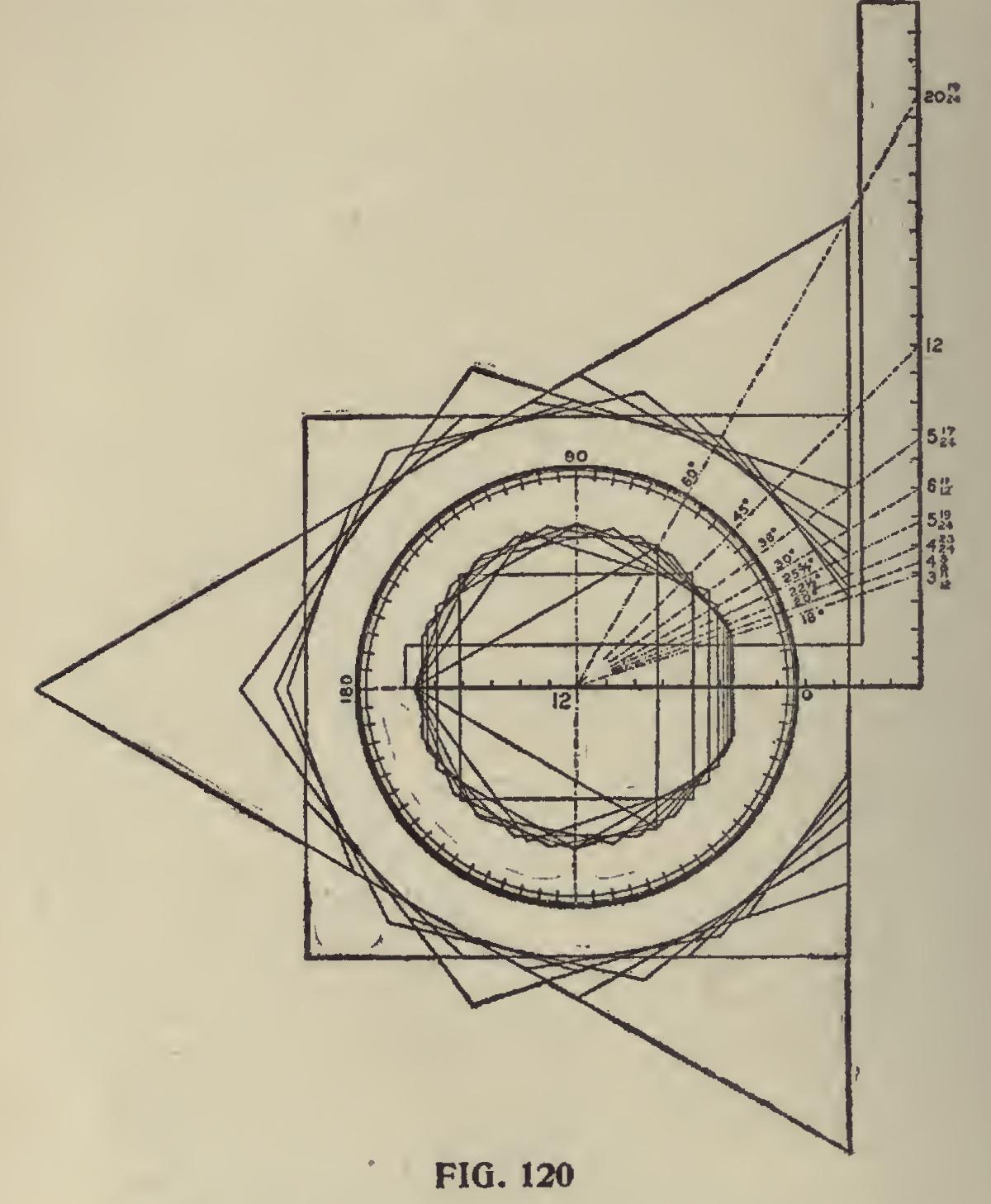

In Fig. 120 are shown two sets of polygons in connection with the degrees and according to the scale, the inner set is drawn to a circumscribed diameter of one foot, while the outer set is drawn to an inscribed diameter of nineteen inches. The starting point in either case is at midway of the sides of the polygons, and the more drawn, the more nearly a true circle they will form. In the former, the corners form the circle and in the latter the central part of the sides lends to the shaping of the circle.

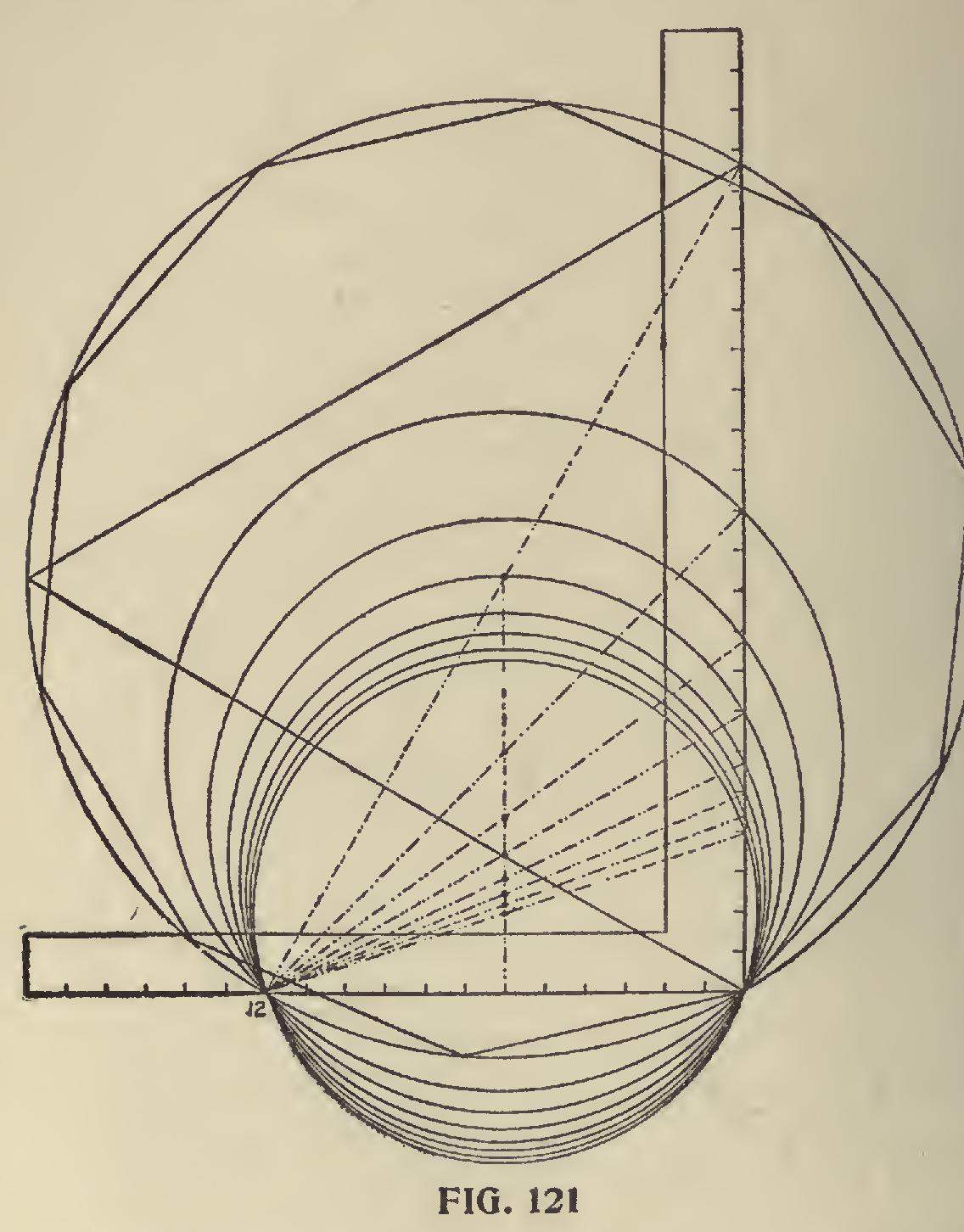

In Fig. 121 are shown the polygon circles. In this illustration each polygon has its individual circle. Beginning with the triangle we show the miter lines for eight of the polygons and by squar ing up from 6 on the tongue and at the intersec tions with the miter lines determine the center of the circles. The reader will notice that each circle cuts at three points on the steel square, also notice the dropping down of the circles and the shadows they cast at the two lower points of the steel square. At first glance it might appear that the circles are not true, but a more careful inspection would show that they are as true as can be described with the compass. The descent of these circles from the triangle down to the decagon is quite rapid, but from this on down it would be a very different thing. The miter lines of a polygon having 180 sides would intersect the blade at one degree, or .21 which is less than one-fourth of an inch, and would be the length of the sides of the polygon with an inscribed diameter of one foot. The miter line for a polygon having 360 sides would intersect the blade at .10476. From this it would appear that the con tinued increase of the sides of a polygon of this size would become too short to be discernible, yet according to trigonometry they could go on and on multiplying in number of sides and the decimal would never be entirely disposed of, leaving it in the infinitesimal or where the polygon really ends and the true circle begins.