California

city, valley, mountains, water, alice, grandfather and suh

Part of the fun came from grand father's pretending that everything would look as it did when he was a boy in the old mining days. He told Alice Chicago would be a little city of 20,000 people, and asked the col ored porter of the car how big it was.

" 'Bout three million people, suh !" " My, my, how it has grown since I was a boy," said grandfather. Alice laughed and grandfather's eyes twinkled. He pretended to be surprised all the time.

Omaha was a big city, too. There was no fort, no fur trading post, no Indians—there were no buffaloes, even. The grassy plains were covered with wheat and cornfields and busy towns. In front of the mountain wall was Denver, a city of more than 250,000.

The iron horse climbed right over the mountains. The railroad looped around the curves and ran along the edges of cliffs and through snow-shed tunnels. " Now," said grandfather, " you'll see bears that are bears.

Dpn't the bears come down to the stations and give you bear hugs sometimes?" he asked the porter.

The Menagerie that Moved Away " No, suh, not that I evah noticed, suh. I reckon they done gone fah back in the moun tains, suh!" " Too bad, too bad," said grandfather. " No bears, no bighorn sheep, no deer, no elk. Well, hello ! There are some prairie dogs, barking at the train !" There were a few Indians at the station, too, and flocks of woolly sheep on the mountain sides with shepherds and collie dogs, and in the valleys were cattle and cowboys on ponies. The snow peaks were , there, and the dusty desert. But every once in a while they came to a mining camp high up on a shelf of rock, or a green valley with irrigation canals running through farms. The water had been brought down from the mountains to make the desert bloom. In the very dryest part of the desert they found Salt Lake City, with 100,000 people, in a big valley covered with farms and orchards between mountains. The city streets were shaded by great trees, the houses set in green lawns.

As they crossed Great Salt Lake on a trestled track, they saw bathers bobbing about like corks. The water was so salt they could not sink.

After a time the train climbed an other steep mountain range, then slid down a long toboggan slope, through forests.

" Now," said grandfather, "I know where I am. I'll show you where I helped my father wash gold out of the gravel in the river bed. It's just below in the valley." This time he wasn't pretending.

He really thought he could find the place, but the mining camp was gone.

Gold mining was now carried on largely in the mountains in deep mines which furnished the ore for mills that crushed the gold-bearing rock. The river banks were lined with towns and farms and golden wheat fields, and on the hillsides were flocks of sheep.

The river grew wider as it met another river flowing north. These ran to gether and into wide water.

" Where are we going now?" asked Alice.

" Through the Golden Gate to where the sun sets." There was a city of a half-million inhabitants, built up the hillsides above the water. At its feet lay a wide harbor full of ships. Across the harbor they looked through a narrow strip of water walled with rocks which looked like a thick stone gate, and through which they could see the sun setting in a great ocean. The city was called San Francisco and its nickname was the City of the Golden Gate. Alice wondered what lay out there over the wide water, and she hoped that some day she might go aboard a ship and go to see.

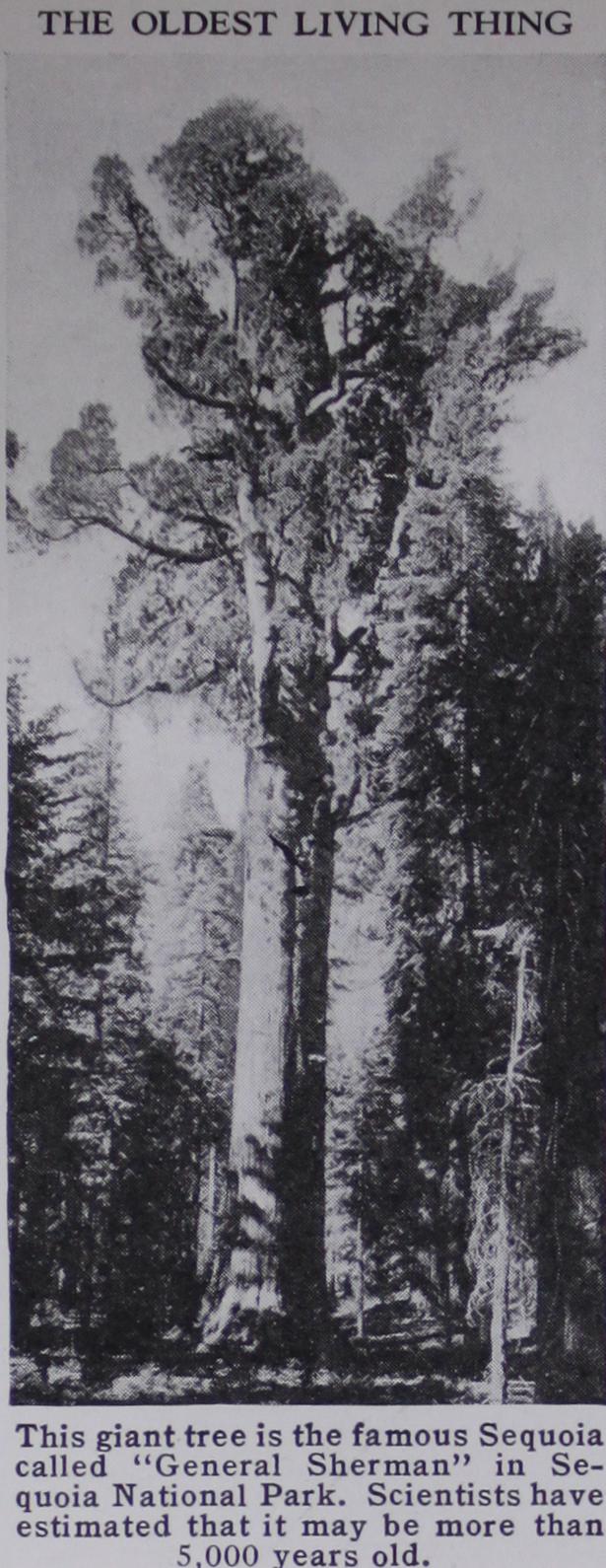

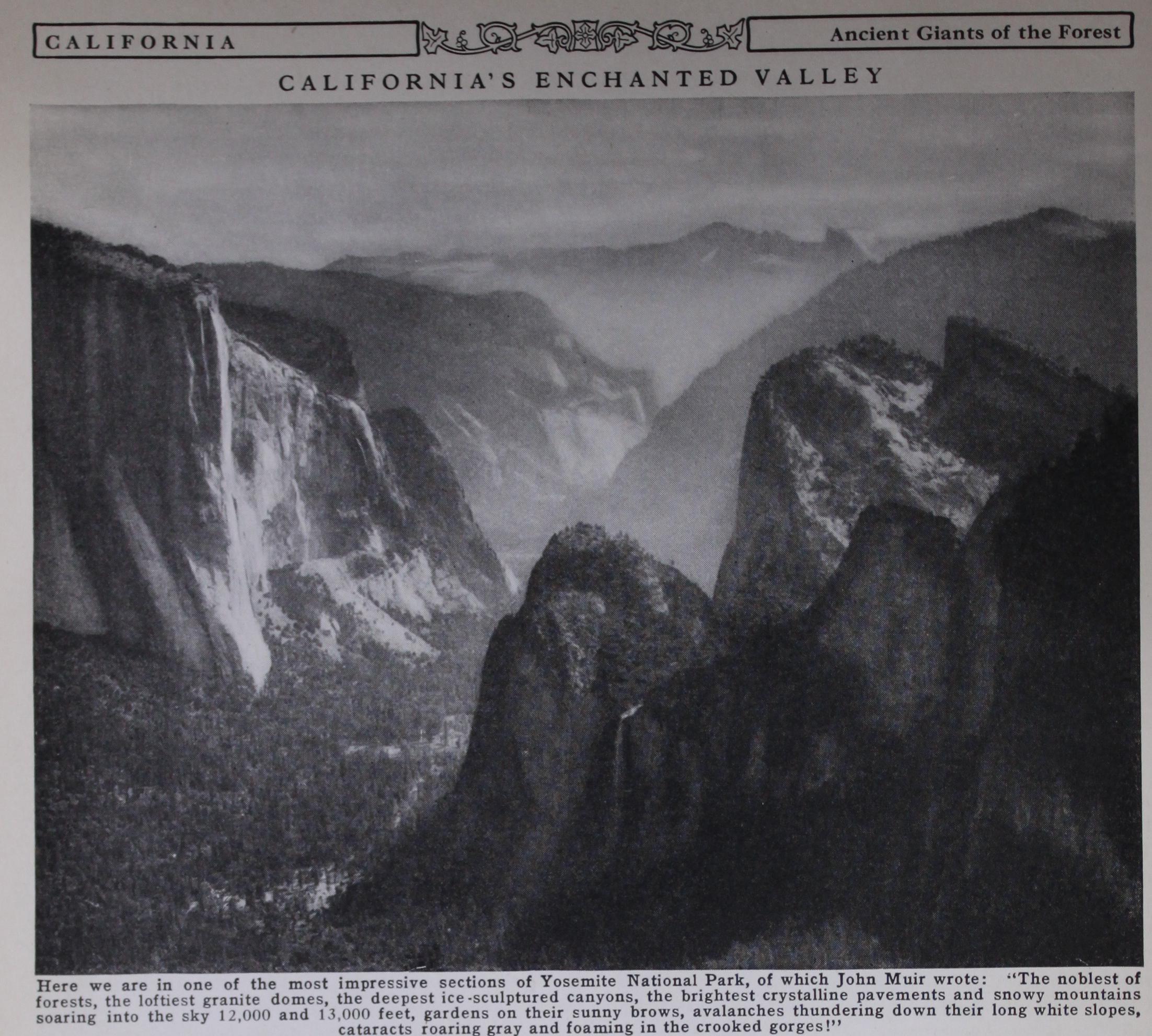

After they left the City of the Golden Gate they saw mountains two miles high, with lakes at the bottoms of their dark green pockets. They saw rivers sunk half a mile, and lined with steeples and towers of rock.

Then they came to the Valley of Delight. Grand father called it Yosemite Valley. There they left the train and got on a stage-coach. One whole day Alice rode on a donkey. They slept in a camp hotel. The valley was a mile deep, walled with mountains.

Rivers fell from the tops of the cliffs, tumbling after each other like Jack and Jill. One of them jumped down a cliff a quarter of a mile and found it such fun that it took a little run over the rocks and jumped again, playing hide-and-seek and follow-the-leader and leap-frog down the rocks. Sometimes a falling brook spread out in a broad sheet, and sometimes it fell so far that it turned to spray and looked like a bride's long veil. The sun turned the spray to rainbows.