Personal Distribution - Income Distribution

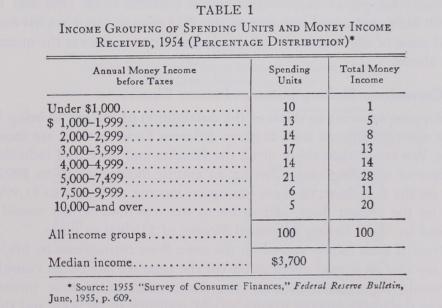

PERSONAL DISTRIBUTION - INCOME DISTRIBUTION by E. T. Weiler The United States, it is sometimes charged, is characterized by "poverty in the midst of plenty," with the "rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer." To prove their point those who make these allegations frequently cite income distribution figures, such as are reproduced below in Table 1 from the Federal Reserve study of consumer finances in the United States in 1954. Using the figures in this table they might argue that one out of four families in 1954 had annual incomes of less than $2,000 and about half of the nation's families had incomes of less than $4,000. Or they might argue that the half of the families getting less than $4,000 per year received in the aggregate only about a quarter of the income while the third of the families getting $5,000 or more per year received about half of the total income. Or to make their point even more strongly, they might point out that the 10 per cent of the families who received less than $1,000 per year received only about 1 per cent of the nation's income while the 5 per cent of the families getting $10,000 or more received about 20 per cent of the total income.

Are these figures correct? The answer is that to the best of our knowledge they are correct. Each year a new study is made and each year the results fit into the same pattern. What is more, different groups have made the same studies for the same years and their findings have been consistent.

Does it follow then that the United States is in fact a country in which there are a few rich families getting large incomes and many poor families struggling for subsistence? The answer is that these figures have to be interpreted with care before they can be used to throw light on the distribution of income in the United States. It has been said of astronomy that it consists largely of making "corrections" (for atmospheric conditions, etc.) to the original observations because uncorrected data would lead to misleading conclusions. And so it is in the use of income distribution figures. Unless used with care they can be misleading. In the paragraphs that follow we shall use data from the 1950 survey of the "Incomes of Families and Persons in the United States" conducted by the Bureau of the Census to shed light on the Federal Reserve figures cited above. Such

fragmentary evidence as is available indicates that there have been no significant changes in income-distribution patterns since 1950 and that the 1950 data can be used to interpret the 1954 figures. Once we have considered some of the "corrections," we shall attempt to answer the question posed above.

Correction: Shifting between Income Classes

Suppose we were to think of the distribution of income as being like a great apartment house with as many different floors as there are income classes. We could then think of all the families and unrelated individuals (in place of spending units) having an annual income of $0 to $999 as living on the first floor, of those having an income of $1,000 to $1,999 as living on the second floor, and so on to the top floor which would be occupied by those having an annual income of $10,000 or more.

Now if each family stayed on the same floor throughout its life, we could say that an annual distribution (of the type we have been considering) would represent accurately the distribution of lifetime incomes. Those in the lower-income groups would continue to be poor and those in the upper-income groups would continue to be rich. Indeed we could go further: we could then talk about the lower third or the upper third of the income recipients as if they consisted of the same people.

But if families moved from year to year to different floors, an annual income distribution would not necessarily reflect the way lifetime incomes were distributed. Suppose that people have small incomes when they are young, large incomes in middle age, and small incomes when they are old. Or suppose that some people were employed in establishments where they were paid high wages when they were working but where the work was unsteady. They would then be paid high incomes in some years and low incomes in others. Even though lifetime incomes were equal, the annual distribution of income would indicate inequalities. It would show that some people were getting low incomes (the young, the old, and the unemployed) and others were getting high incomes. Annual figures unless supplemented by other data can be misleading.