Modifications of Mitosis

chromosomes and ascaris

they are rod-shaped and are often bent in the middle like a V (Figs. 21, 33). They often have this form, too, in embryonic cells, as in the segmentation-stages of the egg in Ascaris (Fig. 24) and other forms. The rods may, however, be short and straight (segmenting eggs of echinoderms, etc.), and may be reduced to spheres, as in the maturation stages of the germ-cells.

Haero)ypital ,Ifiloszs Untifff this name Flemming first described a peculiar modification of the division of the chromosomes that has since been shown to be of very great importance in the early history of the germ-cells, .4. Prophase, chromosomes in the form of scattered rings, each of which represents two daughter-chromosomes joined end to end. B. The rings ranged about the equator of the spindle and dividing; the swellings indicate the ends of the chromosomes. C. The same viewed from the spindle-pole. D. 1 iiagram (liermann I showing the central spindle, asters and centrosomes, and the contractile mantle-fibres attached to the rings (one of the latter dividing).

though it is not confined to them. In this form the chromosomes split at an early period, but the halves remain united by their ends. Lach double chromosome then opens out to form a closed ring ( Fig. 26), which by its mode of origin is shown to represent two daughter-chromosomes, each forming half of the ring, united by their ends. The ring finally breaks in two to form two U-shaped chromosomes which diverge to opposite poles of the spindle as usual. As will be shown in Chapter V., the divisions by which the germ-cells are matured are in many cases of this type ; but the primary rings here represent not two but four chromosomes, into which they afterwards break up.

3.

Bivalent and Plurivalent Chromosomes The last paragraph leads to the consideration of certain variations in the number of the chromosomes. Boveri discovered that the species Ascaris megalocephala comprises two varieties which differ in no visible respect save in the number of chromosomes, the germ-nuclei of one form (" variety bivalens " of Hertwig) having two chromosomes, while in the other form ("variety univalens") there is but one. Brauer discovered a similar fact in the phyllopod Artemia, the number of somatic chromosomes being 168 in some individuals, in others only 84 (p. 205).

It will appear hereafter that in some cases the primordial germcells show only half the usual number of chromosomes, and in Cyclops, the same is true, according to Hacker, of all the cells of the early cleavage-stages.

In all cases where the number of chromosomes is apparently reduced (" pseudo-reduction " of Ruckert) it is highly probable that each chromatin-rod represents not one but two or more chromosomes united together, and Hacker has accordingly proposed the terms " bivalent " and " plurivalent " for such The truth of this view, which originated with vom Rath, is, I think, conclusively shown by the case of Artemia described at p. 203, and by many facts in the maturation of the germ-cells hereafter considered. In Ascaris we may regard the chromosomes of Hertwig's " variety univalens " as really bivalent or double ; i.e. equivalent to two such chromosomes as appear in "variety bivalens." These latter, however, are probably in their turn plurivalent, i.e. represent a number of units of a lower order united together; for, as described at p. t t 1, each of these normally breaks up in the somatic cells into a large number of shorter chromosomes closely similar to those of the related species Ascaris lumbricoides, where the normal number is 24.

Hacker has called attention to the striking fact that plurivalent mitosis is very often of the heterotypical form, as is very common in the maturation mitoses of many animals (Chapter V.), and often occurs in the early cleavages of Ascaris ; but it is doubtful whether this is a universal rule.

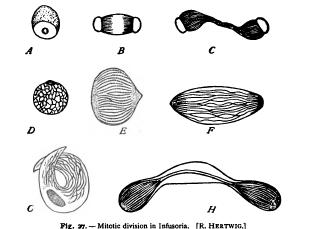

4. Mitosis in the Unicellular Plants and Animals The process of mitosis in the one-celled plants and animals has a peculiar interest, for it is here that we must look for indications of A-C. Macronucleus of Spirochona, showing pole-plates. D-H. Successive stages in the division of the micronucleus of Paramcrcium. D. The earliest stage, showing reticulum. G. Following stage (" sickle-form ") with nucleolus. E. Chromosomes and pole-plates. F. Late ana H. Final phase.