Modifications of Mitosis

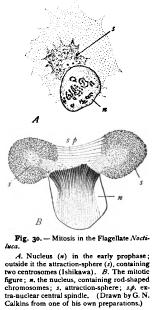

chromosomes and formed

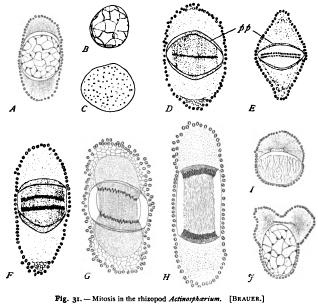

Noctiluca, finally, appears to have attained the condition characteristic of the higher forms. Here, as Ishikawa has shown, the cell contains a typical extra-nuclear centrosome and attraction-sphere lying in the cytoplasm, precisely as in Ascaris (Fig. 3o). By division of centrosome and sphere a typical central spindle is formed, about which the nucleus wraps itself, and mitosis proceeds much as in the higher types, except that the nuclear membrane does not disappear. 1 Regarding the history of the chromatin the most thorough observations have been made by Schewiakoff in Euglypha and Brauer in Actinosphcerium. In the former case a segmented spireme arises from the resting reticulum, and long, rod-shaped chromosomes are formed, which are stated to split lengthwise as in the usual forms of mitosis. The nuclear membrane persists throughout, and the entire mitotic figure, except the minute asters, is formed inside it (Fig. 28). In Actinosphterium, on the other hand, there is no true spireme stage, and no rod-shaped chromosomes are at first formed. The reticulum breaks up into a large number of granules which give rise to an equatorial plate, divide by fission, and are distributed to the daughter-nuclei.

A.

Nucleus and surrounding structures in the early prophase; above and below the reticular nucleus lie the semilunar " pole-plates," and outside these the cytoplasmic masses in which the asters afterward develop. B. Later stage of the nucleus. D. Mitotic figure in the metaphase, showing equatorial plate, intra-nuclear spindle, and pole-plates (p.p.). C. Equatorial plate, viewed en face, consisting of double chromatin-granules. E. Early anaphase. F. G. Later anaphases. H. Final anaphase. I. Telophase; daughter-nucleus forming, chromatin in loop-shaped threads; outside the nuclear membrane the centrosome, already divided, and the aster. 7. Later stage; the daughter-nucleus established; divergence of the centrosomes. Beyond this point the centrosomes have not been followed.

Only in the late anaphase (telophase) do these granules arrange themselves in threads (Fig. 31, 1), and this process is apparently no more than a forerunner of the reticular stage. This case is a very convincing argument in favour of the view that the formation and splitting of chromosomes is secondary to the division of the ultimate chromatin-granules.

(Cf. pp. 78 and 221.) Richard Hertwig's studies on Infusoria and those of Lauterborn on Flagellates indicate that here also no longitudinal splitting of the chromatin-threads occurs and that the division must be referred to the individual chromatin-granules. Ishikawa describes a peculiar longitudinal splitting of chromosomes in Noctiluca, but Calkins' studies indicate that the latter observer has probably misinterpreted certain stages and that the division probably takes place in a somewhat different manner. A typical spireme and chromosome

formation has also been described by Lauterborn in the Diatoms ('93).

In none of the foregoing cases does the nuclear membrane disappear. In the gregarines, however, the observations of Wolters ('9 ) and Clarke ('95) indicate that the membrane does not persist, and that a perfectly typical mitotic figure is formed.

To sum up : The facts at present known indicate that the unicellular forms exhibit forms of mitosis that are in some respects transitional from the typical mitosis of higher forms to a simpler type. The asters may be reduced (Rhizopods) or wanting (Infusoria); the spindle is typically formed inside the nucleus, either by division of an intra-nuclear " nucleolo-centrosome " (Euglena, Amoeba), or possibly by rearrangement of the chromatic substance without a differentiated centrosome (? micronuclei of Infusoria). In every case the essential fact in the history of the chromatin is a division of the chromatingranules ; but this may be preceded by their arrangement in threads or chromosomes (Euglypha, Diatoms) or may not (Actinospharium). These facts point towards the conclusion that centrosome, spindle, and chromosomes are all secondary differentiations of the primitive nuclear structure, and indicate that the asters and attraction-spheres may be historically a later acquisition developed in the cytoplasm after the differentiation of the centrosome.

5. Pathological Mitoses

Under certain circumstances the delicate mechanism of cell-division may become deranged, and so give rise to various forms of pathological mitoses. Such a miscarriage may be artificially produced, as Hertwig, Galeotti, and others have shown, by treating the dividingcells with poisons and other chemical substances (quinine, chloral, nicotine, potassic iodide, etc.). Pathological mitoses may, however, occur without discoverable external cause ; and it is a very interesting fact, as Klebs, Hansemann, and Galeotti have especially pointed out, that they are of frequent occurrence in abnormal growths such as cancers and tumours.

The abnormal forms of mitoses are arranged by Hansemann in two general groups, as follows : (1) asymmetrical mitoses, in which the chromosomes are unequally distributed to the daughter-cells, and (2) multipolar mitoses, in which the number of centrosomes is more than two, and more than one spindle is formed. Under the first group are included not only the cases of unequal distribution of the daughter-chromosomes, but also those in which chromosomes fail to be drawn into the equatorial plate and hence are lost in the cytoplasm.