General Sketch of the Ovum

chromosomes and germ-nuclei

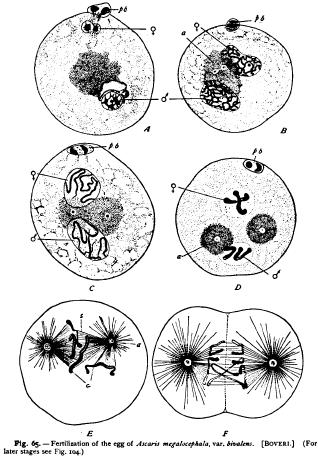

This conclusion received a strong support in the year 1883, through the splendid discoveries of Van Beneden on the fertilization of the thread-worm, Ascaris megalocephala, the egg of which has since ranked with that of the echinoderm as a classical object for the study of cellproblems. Van Beneden's researches especially elucidated the structure and transformations of the germ-nuclei, and carried the analysis of fertilization far beyond that of Hertwig. In Ascaris, as in all other animals, the sperm-nucleus is extremely minute, so that at first sight a marked inequality between the two sexes appears to exist in this respect. Van Beneden showed not only that the inequality in size totally disappears during fertilization, but that the two nuclei undergo a parallel series of structural changes which demonstrate their precise morphological equivalence down to the minutest detail ; and here, again, later researches, foremost among them those of Boveri, Strasburger, and Guignard, have shown that, essentially, the same is true of the germ-cells of other animals and of plants. The facts in Ascaris (variety bivalens) are essentially as follows (Fig. 65) : After the entrance of the spermatozoon, and during the formation of the polar bodies, the sperm-nucleus rapidly enlarges and A. The spermatozoon has entered the egg, its nucleus is shown at d; beside it lies the granular mass of " archoplasm" (attraction-sphere) ; above are the closing phases in the formation of the second polar body (two chromosomes in each nucleus). B. Germ-nuclei e) in the reticular stage ; the attraction-sphere (a) contains the dividing centrosome. C. Chromosomes forming in the germ-nuclei ; the centrosome divided. D. Each germ-nucleus resolved into two chromosomes ; attraction-sphere (a) double. E. Mitotic figure forming for the first cleavage; the chromosomes (c) already split. F. First cleavage in progress, showing divergence of the daughterchromosomes towards the spindle-pole:, (only three chromosomes shown).

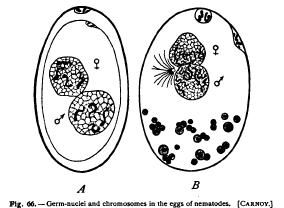

finally forms a typical nucleus exactly similar to the egg-nucleus. The chromatin in each nucleus now resolves itself into two long, worm-like chromosomes, which are exactly similar in form, size, and staining reaction in the two nuclei. Next, the nuclear membrane fades away, and the four chromosomes lie naked in the egg-substance. Every trace of sexual difference has now disappeared, and it is impossible to distinguish the paternal from the maternal chromosomes (Figs. 65, D, E). Meanwhile an amphiaster has been developed which, with the four chromosomes, forms the mitotic figure for the first cleavage of the ovum, the chromatic portion of which has been synthetically formed by the union of two equal germ-nuclei. The A. Egg of nematode parasitic in Scyllium; the two germ-nuclei in apposition, each containing four chromosomes; the two polar bodies above. B. Egg of Filaroides; each germ-nucleus with eight chromosomes; polar bodies above, deutoplasm-spheres below.

later phases follow the usual course of mitosis. Each chromosome splits lengthwise into equal halves, the daughter-chromosomes are transported to the spindle-poles, and here they give rise, in the usual manner, to the nuclei of the two-celled stage. Each of these nuclei, therefore, receives exactly equal amounts of paternal and maternal chromatin.

These discoveries were confirmed and extended in the case of Ascaris by Boveri and by Van Beneden himself in 1887 and 1888 and in several other nematodes by Carnoy in 1887. Carnoy found

the number of chromosomes derived from each sex to be in Coronilla 4, in Ophiostomum 6, and in Filaroides 8. A little later Boveri ('9o) showed that the law of numerical equality of the paternal and maternal chromosomes held good for other groups of animals, being in the sea-urchin Echinus 9, in the worm Sagitta 9, in the medusa Tiara 14, and in the mollusk Pterotrachea i6 from each sex. Similar results were obtained in other animals and in plants, as first shown by Guignard in the lily ('91), where each sex contributes 12 chromosomes. In the onion the number is 8 (Strasburger) ; in the annelid ophryotrochait is only 2 from each sex (Korschelt). In all these cases the number contributed by each'is one-half the number characteristic of the body-cells. The union of two germ-cells thus restores the normal number, and thus we find the explanation of the remarkable fact commented on at p. 48 that the number of chromosomes in sexually produced organisms is always even.' These remarkable facts demonstrate the two germ-nuclei to be in a morphological sense precisely equivalent, and they not only lend very strong support to Hertwig's identification of the nucleus as the bearer of hereditary qualities, but indicate further that these qualities must be carried by the chromosomes ; for their precise equivalence in number, shape, and size is the physical correlative of the fact that the two sexes play, on the whole, equal parts in hereditary transmission. And thus we are finally led to the view that chromatin is the physical basis of inheritance, and that the smallest visible units of structure by which inheritance is effected are to be sought in the chromatin-granules or chromomeres.

2.

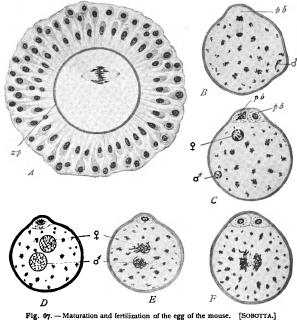

The Centrosome in Fertilization The origin of the centrosomes and of the amphiaster, by means of which the paternal and maternal chromosomes are distributed and the egg divides, is still in some measure a matter of dispute. In a large number of cases, however, it is certainly known that the egg-centrosome disappears before or during fertilization and its place is taken by a new centrosome which is introduced by the spermatozoon and divides into two to form the cleavage-amphiaster. This has been conclusively demonstrated in several forms (various echinoderms, annelids, nematodes, tunicates, mollusks, and vertebrates) and established with a high degree of probability in many others (insects, crustacea). In every accurately known case, moreover, the centrosome has been traced to the middle-piece of the spermatozoon ; e.g. in sea-urchins (Hertwig, Boveri, Wilson, Mathews, Hill), in the axolotl (Fick), in the tunicate Phallusia (Hill), probably in the earthworm, Allolobophora (Foot), in the butterfly Pieris (Henking), and in the gasteropod Physa (Kostanecki and Wierzejski). The agreement between forms so diverse is very strong evidence that this must be regarded as the typical derivation of the The facts may be illustrated by a brief description of the pheA. The ovarian egg still surrounded by the follicle-cells and the membrane (z.p., zona pellucida); the polar spindle formed. B. Egg immediately after entrance of the spermatozoon (sperm-nucleus at a). C. The two germ-nuclei (6, 9) still unequal; polar bodies above. D. Germ-nuclei approaching, of equal size. E. The chromosomes forming. F. The minute cleavage-spindle in the centre; on either side the paternal and maternal groups of chromosomes.