Union of the Germ-Cells

nuclei and chromosomes

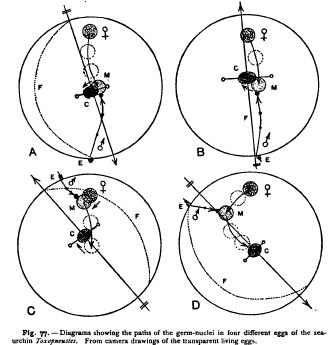

mined by at least two different factors, one of which is an attraction or other dynamical relation between the nuclei and the cytoplasm, the other an attraction between the nuclei. The former determines In all the figures the original position of the egg-nucleus (reticulated) is shown at the point at which the spermatozoon enters at E (entrance-cone). Arrows indicate the paths traversed by the nuclei. At the meeting-point (Al) the egg-nucleus is dotted. The cleavage-nucleus in its final position is ruled in parallel lines, and through it is drawn the axis of the resulting cleavagefigure. The axis of the egg is indicated by an arrow, the point of which is turned away from the micromere-pole. Plane of first cleavage, passing near the entrance-point, shown by the curved dotted line.

the entrance-path of the sperm-nucleus, while both factors probably operate in the determination of the copulation-path along which it travels to meet the egg-nucleus. The real nature of neither factor is known.

Hertwig first called attention to the fact — which is easy to observe in the living sea-urchin egg— that the egg-nucleus does not begin to move until the spermnucleus has penetrated some distance into the egg and the sperm-aster has attained a considerable size ; and Conklin ('94) has suggested that the nuclei are passively drawn together by the formation, attachment, and contraction of the astral rays. While this view has some facts in its favour, it is, I believe, untenable, for many reasons, among which may be mentioned the fact that neither the actual paths of the pro-nuclei nor the arrangement of the rays support the hypothesis ; nor does it account for the conjugation of nuclei when no astral rays are developed (as in Protozoa), or are insignificant as compared with the nuclei (as in plants). I have often observed in cases of dispermy in the sea-urchin, that both sperm-nuclei move at an equal pace towards the egg-nucleus ; but if one of them meets the egg-nucleus first, the movement of the other is immediately retarded, and only conjugates with the egg-nucleus, if at all, after a considerable interval ; and in polyspermy, the eggnucleus rarely conjugates with more than two sperm-nuclei. Probably, therefore, the nuclei are drawn together by an actual attraction which is neutralized by union, and their movements are not improbably of a chemotactic character.

3.

Union of the Germ-nuclei. The Chromosomes The earlier observers of fertilization, such as Auerbach, Strasburger, and Hertwig, described the germ-nuclei as undergoing a complete fusion to form the first embryonic nucleus, termed by Hertwig the cleavage- or segmentation-nucleus. As early as 1881, however,Mark clearly showed that in the slug Limax this is not the case, the two nuclei merely becoming apposed without actual fusion. Two years later appeared Van Beneden's epoch-making work on Ascaris, in which it was shown not only that the nuclei do not fuse, but that they give rise to two independent groups of chromosomes which separately enter the equatorial plate and whose descendants pass separately into the daughter-nuclei. Later observations have given the strongest reason to believe that, as far as the chromatin is concerned, a true fusion of the nuclei never takes place during fertilization, and that the paternal and maternal chromatin may remain separate and distinct in the later stages of development — possibly throughout life (p. 219). In this regard two general classes may be distinguished. In one, exemplified by some echinoderms, by Amphioxus, Phallusia, and some other animals, the two nuclei meet each other when in the reticular form, and apparently fuse in such a manner that the chromatin of the resulting nucleus shows no visible distinction between the paternal and maternal moieties. In the other class, which includes most accurately known cases, and is typically represented by Ascaris (Fig. 65) and other nematodes, by Cyclops (Fig. 72), and by Pterotrachea (Fig. 68), the two nuclei do not fuse, but only place themselves side by side, and in this position give rise each to its own group of chromosomes. On general grounds we may confidently maintain that the distinction between the two classes is only apparent, and probably is due to corresponding differences in the rate of development of the nuclei, or in the time that elapses before their union.' If this time be very short, as in echinoderms, the nuclei unite before the chromosomes are formed. If it be more prolonged, as in Ascaris, the chromosome-formation takes place before union.

With a few exceptions, which are of such a character as not to militate against the rule, the number of chromosomes arising from the germ-nuclei is always the same in both, and is one-half the number characteristic of the tissue-cells of the species. By their union, therefore, the germ-nuclei give rise to an equatorial plate containing the typical number of chromosomes. This remarkable discovery was first made by Van Beneden in the case of Ascaris, where the number of chromosomes derived from each sex is either one or two. It has since been extended to a very large number of animals and plants, a partial list of which follows.