Practical Carpentry

arc, line, fig, angle, circle, equal, straight and describe

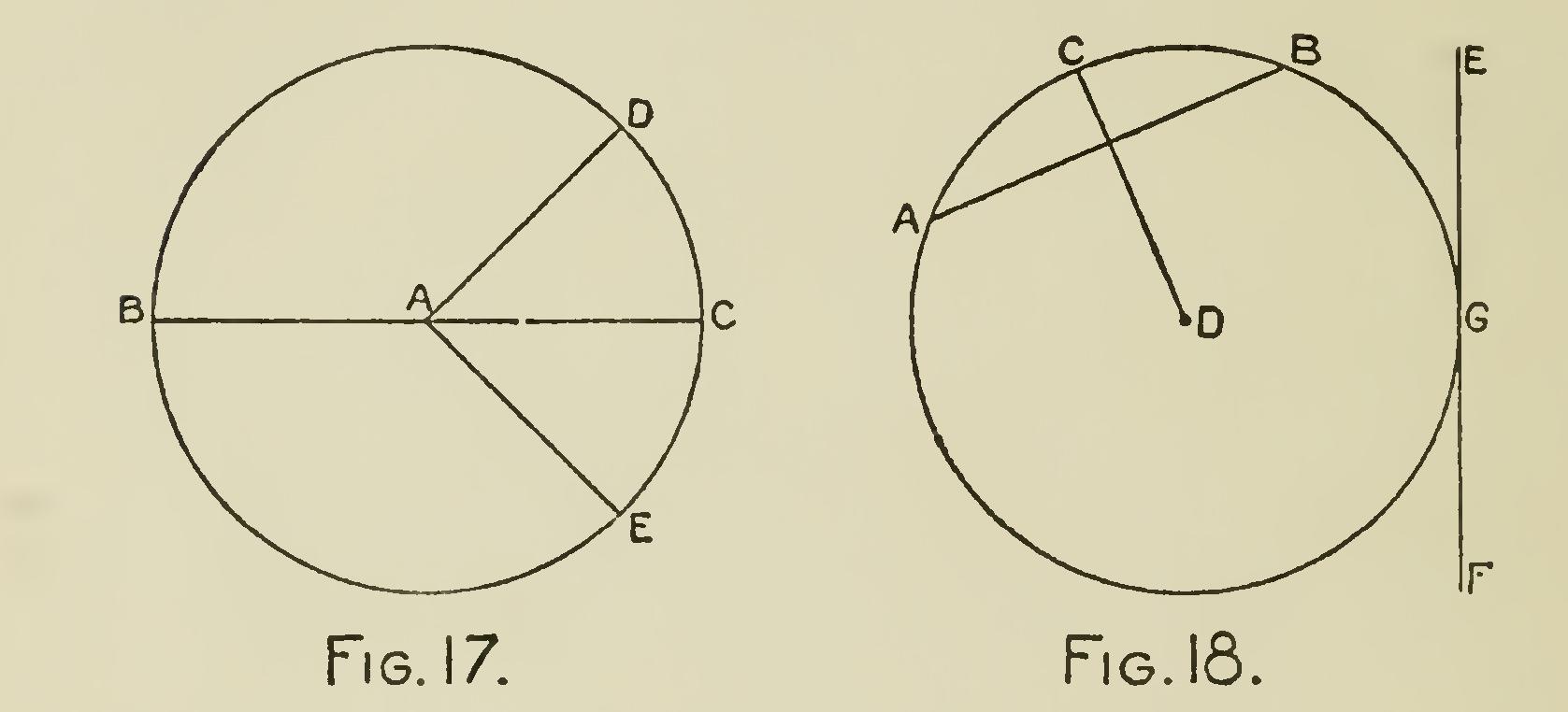

The Chord of an Arc is any straight line drawn from one point in the circumference of a circle to another, joining the extremeties of the arc, and dividing the circle either into two equal or unequal parts. If into two equal parts, the chord is also the diameter, and the space included between the arc and the diameter, on either side of it, is called a semicircle. If the parts cut off by the chord are unequal, each of them is called a segment of a circle; but, unless otherwise stated, it is always understood that the smaller arc or segment is spoken of as in Fig. 18 A B is the chord of the arc AC B.

If a straight line be drawn from the center of a circle to meet the chord of an arc perpendicularly, as D C, in Fig. 18, it will divide the chord into two equal parts, and if the straight line be pro duced to meet the arc, it will also divide it into two equal parts, as A C, C B.

Each half of the chord is called the sine of the half arc to which it is opposite; and the line drawn from the center to meet the chord perpen dicularly is called the co-sine of the half-arc. Consequently, the radius, the sine, the co-sine of an arc form a right angle.

A Tangent is any straight line which touches the circumference of a circle in one point, which is called the point of contact, as in the tangent E G F in Fig. 18.

An arc is any portion of the circumference of a circle, as A C B in Fig. 18.

It may not be improper to remark here that the terms circle and circumference are frequently misapplied. Thus we say, describe a circle from a given point, instead of saying describe the cir cumference of a circle—the circumference being the curved line thus described, everywhere equally distant from a point within it, called the center; whereas the circle is properly the superficial space included within that circumference.

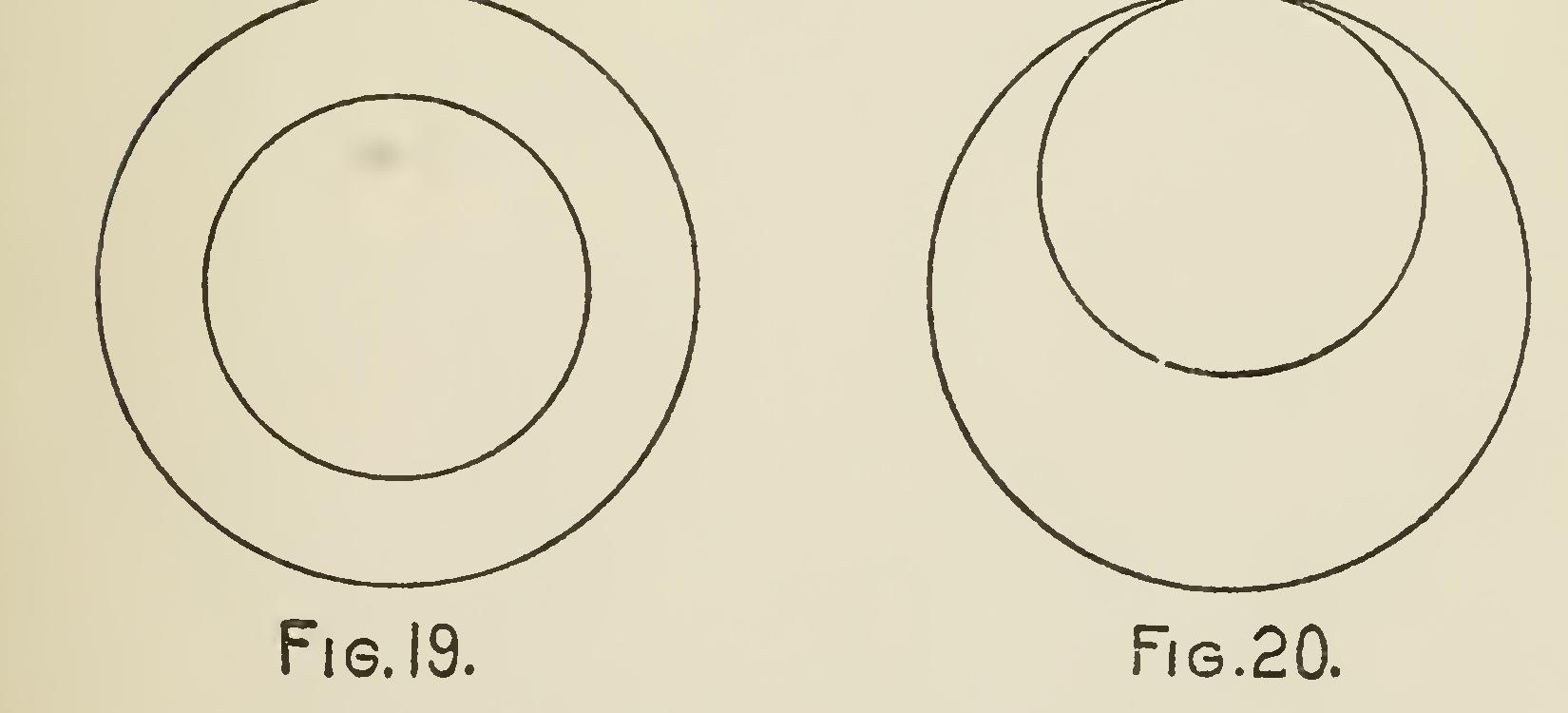

Concentric Circles

are circles within circles, described from the same center; consequently their circumferences are parallel to one another, as in Fig. 19.

Eccentric Circles

are those which are not de scribed from the same center; eccentric circles may also be tangent circles ; that is, such as come in contact in one point, only, as Fig. 20.

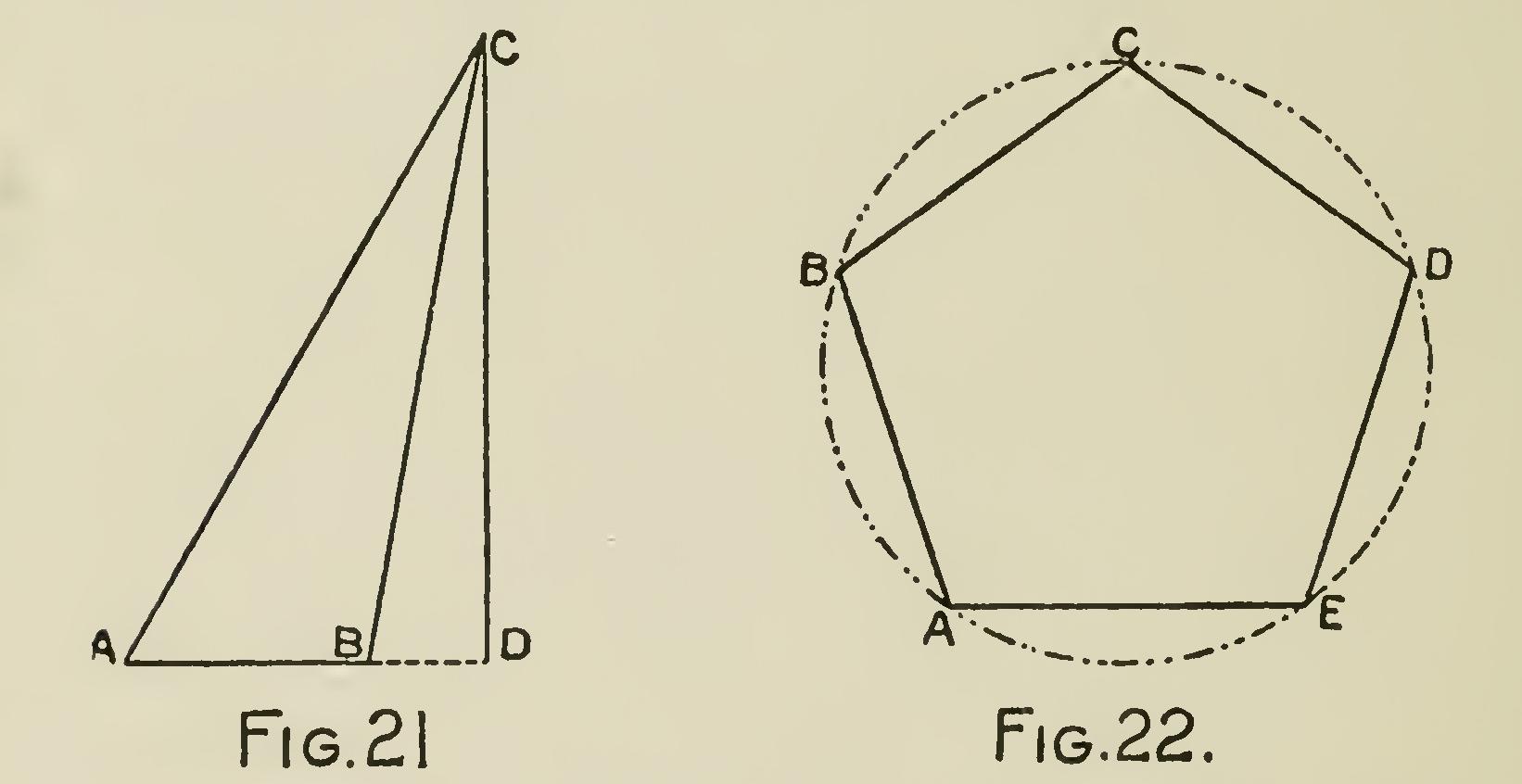

Altitude.

The height of a triangle or other figure is called its altitude. To measure the alti tude, let fall a straight line from the vertex or highest point in the figure, perpendicular to the base or opposite side ; or, to the base continued, as at B D, Fig. 21, should the form of the figurerequire its extension. Thus C D is the altitude of the triangle A B C.

An Inscribed Polygon

is one which, like A B C D E in Fig. 22, has all its angles in the circum ference. The circle is then said to circumscribe such a figure.

We have now described all the figures we shall require for the purpose of thoroughly under standing all that will follow in this book; but we would like to say right here that the student who has time should not stop at this point in the study of geometry, for the time spent in obtaining a thorough knowledge of this useful science will bring in better returns than if expended for any other purpose.

Problems in Geometry.

We will now proceed to explain how the figures we have described can be constructed. There are several ways of constructing nearly every figure we produce ; but we have chosen those methods that seem to us the best, but to save space have given only those which are most essential in the study of practical carpentry.

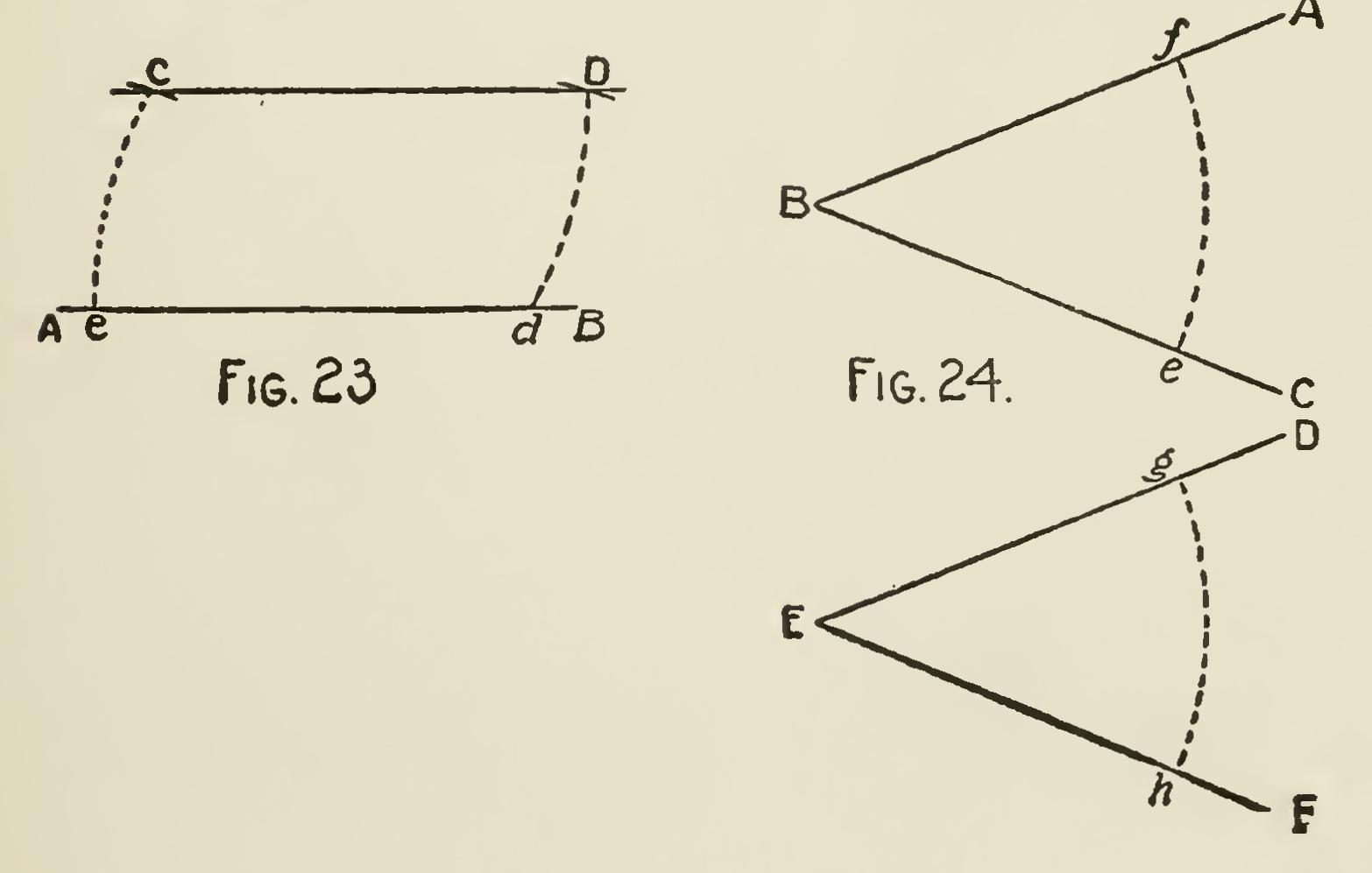

Problem 1.—Through a given point C (Fig. 23), to draw a straight line parallel to a given straight line A B: In A B (Fig. 23) take any point d, and from d as a center with the radius dC, describe an arc Ce, cutting AB in e, and from C as a center, with the same radius, describe the arc dD, make dD equal to Ce, join C D, and it will be parallel to A B.

Problem 2.—To make an angle equal to a given rectilineal angle: From a given point E (Fig. 24), upon the straight line E F, to make an angle equal to the given angle A B C. From the angular point B, with any radius, describe the arc ef, cutting B C and B A in the points e and f. From the point E on E F, with the same radius, describe the arc hg, and make it equal to the arc ef ; then from E, through g, draw the line E D: the angle D E F will be equal to the angle A B C.

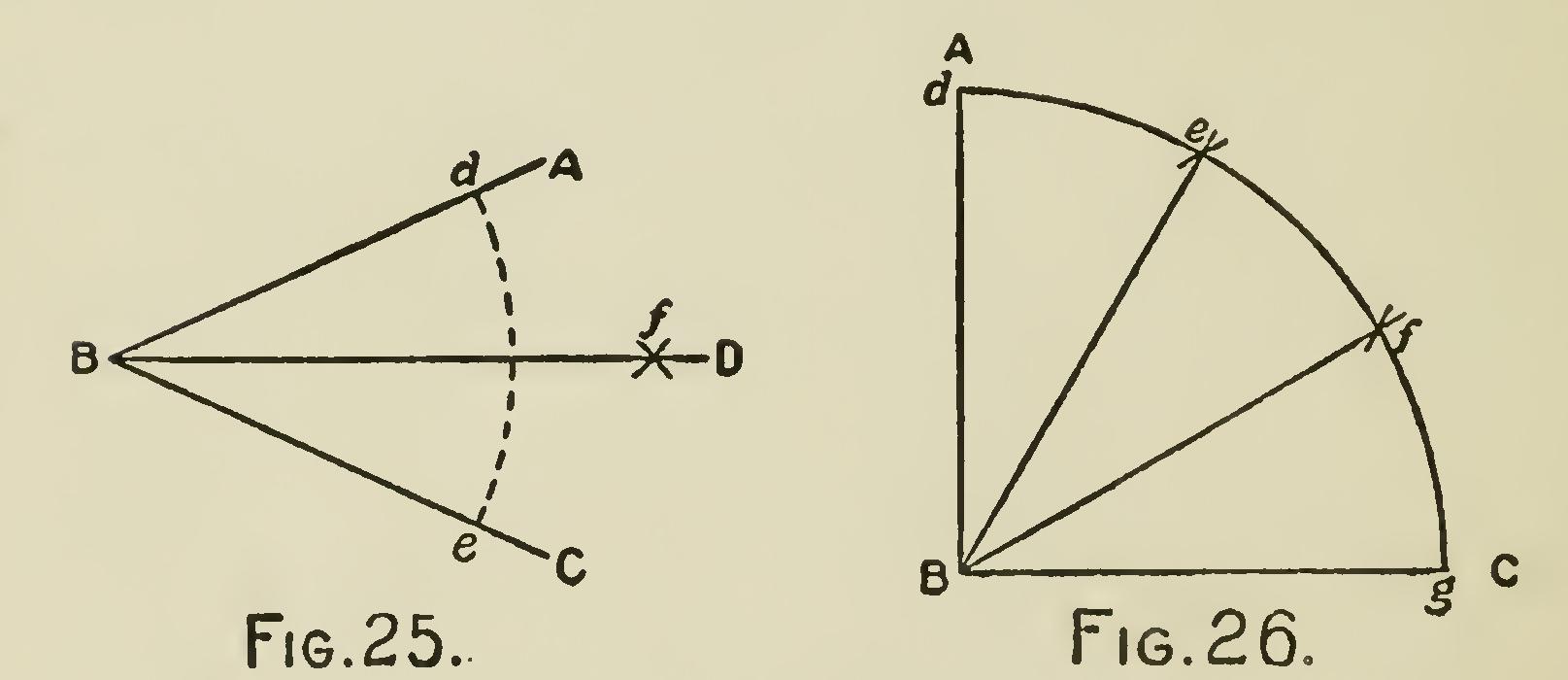

Probelm 3.—To bisect a given angle: Let A B C (Fig. 25) be the given angle. From the an gular point B, with any radius, describe an arc cutting B A and B C in the points d and e ; also, from the points d and e as centers, with any radius greater than half the distance between them, describe arcs cutting each other in f ; through the points of intersection f, draw B f D: the angle A B C is bisected by the straight line B D ; that is, it is divided into two equal angles, A B D and C B D.