Practical Carpentry

arc, lines, length, chord, equal, ab, draw and join

The following method of finding the length of an arc is equally simple and practical, and not less accurate than the one just given : Let AB (Fig. 48) be the given arc. Find the center C, and join AB, BC and CA. Bisect the arc AB in D, and join also CD ; then through the point D draw the straight line EDF, at right angles to CD, and meeting CA and CB produced in E and F. Again, bisect the lines AE and BF in the points G and H. A straight line GH, joining these points, will be a very near approach to the length of the arc AB.

Seeing that, in very small arcs, the ratio of the chord to the double tangent or, which is the same thing, that of a side of the inscribed to a side of the circumscribing polygon, approaches to a ratio of equality, an arc may be made so small, that its length shall differ from either of these sides by less than any assignable quantity; therefore, the arithmetical mean between the two must differ from the length of the arc itself by less than any that can be assigned. Consequently the smaller the given arc, the more nearly will the line found by the last method approximate to the exact length of the arc. If the given are is above 60 degrees, or two-thirds of a quadrant, it ought to be bisected, and the length of the semi-arc thus found being double, will give the length of the whole arc.

These problems are very useful in obtaining the lengths of veneers or other materials re quired for bending round soffits of doors and window-heads.

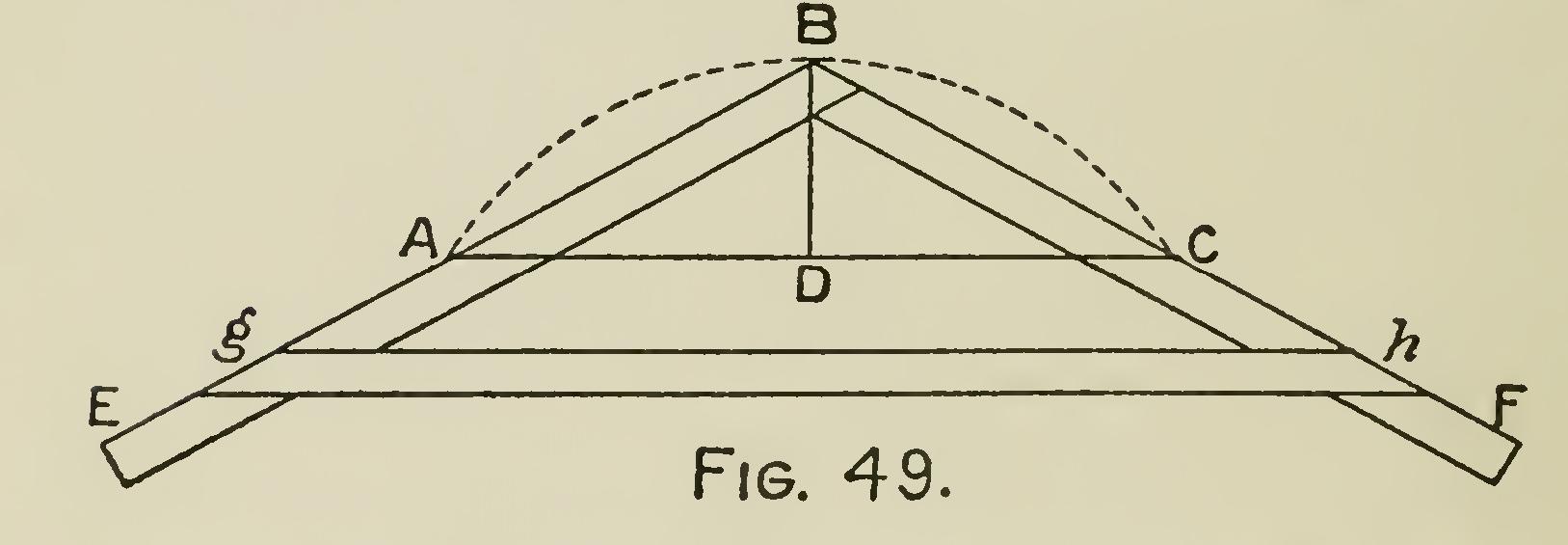

Problem 24.—To describe the segment of a circle by means of two laths, the chord and versed sine being given: Take two rods, EB, BF (Fig. 49), each of which must be at least equal in length to the chord of the proposed segment AC; join them together at B, and expand them, so that their edges shall pass through the extremi ties of the chord, and the angle where they join shall be on the extremity B of the versed sine DB, or height of the segment. Fix the rods in that position by the cross piece gh, then by guid ing the edges against pins in the extremities of the chord line AC, the curve ABC will be described by the point B.

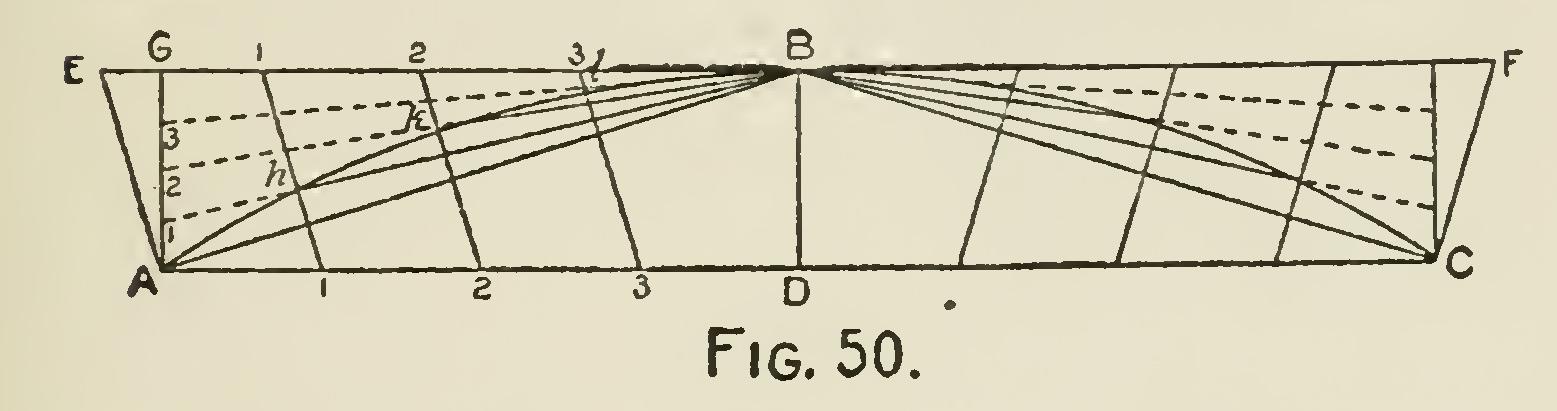

Problem 25.—Having the chord and versed sine of the segment of a circle of large radius given, to find any number of points in the curve by means of intersecting lines: Let AC be the chord and DB the versed sine. Through B (Fig. 50) draw EF indefinitely and parallel to AC; join AB, and draw AE at right angles to AB.

Draw also AG at right angles to AC, and di vide AD and EB into the same number of equal parts, and number the divisions from A and E, respectively, and join the corresponding numbers by the lines, 11, 22, 33. Divide also AG into the same number of equal parts as AD or EB, num bering the divisions from A upwards, 1, 2, 3, etc.; and from the points 1, 2 and 3 draw lines to B and the points of interesection of these with the other lines at h, k, 1, will be points in the curve required. Same with BC.

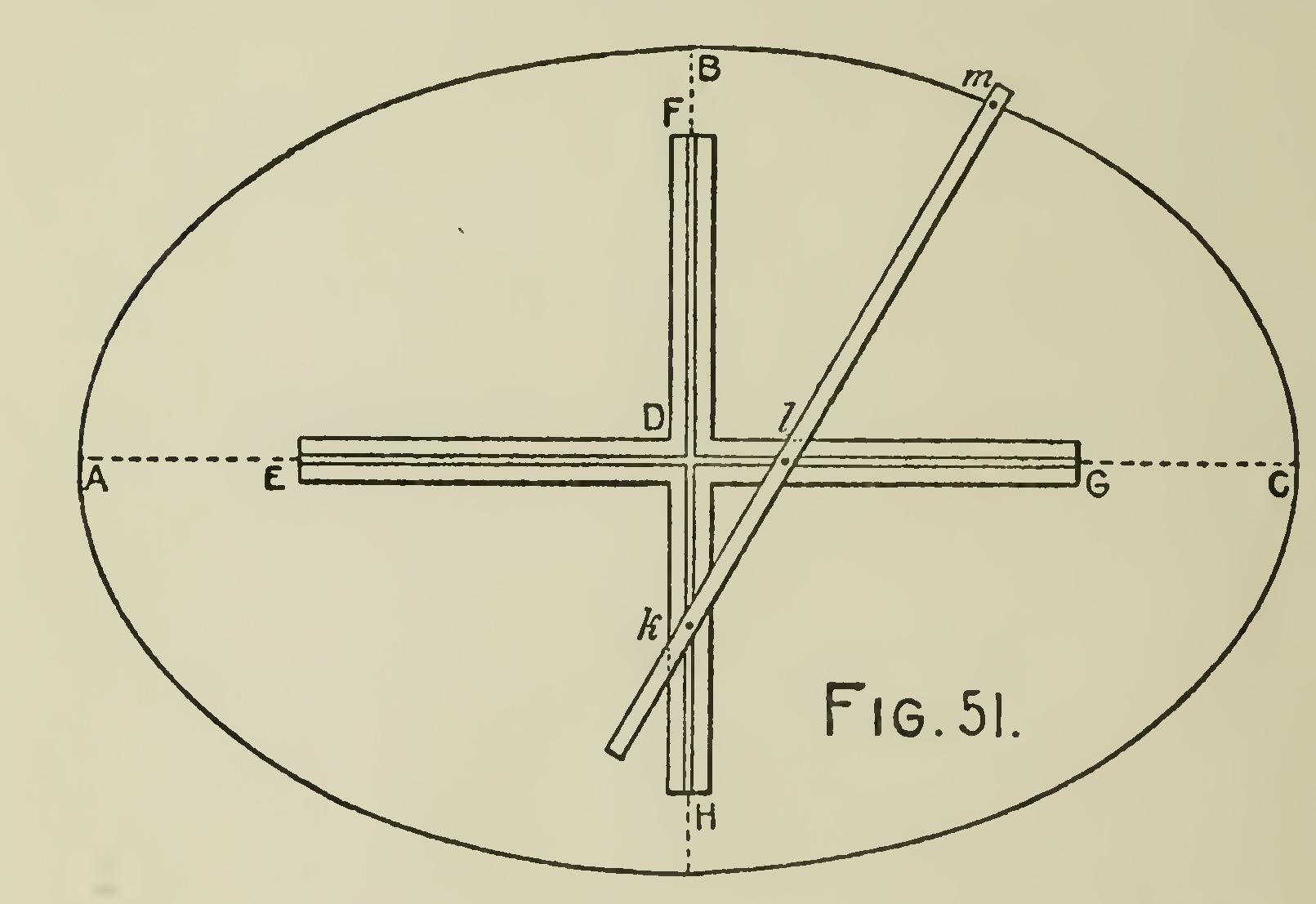

Problem 26.—To draw an ellipse with the trammel: The trammel is an instrument con sisting of two principal parts; the fixed part in the form of a cross EFGH (Fig. 51), and the movable piece or tracer klm. The fixed piece is made of two rectangular bars or pieces of wood, of equal thickness, joined together so as to be in the same plane. On one side of the frame so formed, a groove is made, forming a right-angled cross. In the groove two studs, k and 1, are fitted to slide freely and carry attached to them the tracer klm. The tracer is generally made to slide through the socket fixed to each stud, and provided with a screw or wedge, by which the distance apart of the studs may be regulated. The tracer has another slider m, also adjustable, which car ries a pencil or point. The instrument is used as follows : Let AC be the major, and HB the minor axis of an ellipse: lay the cross of the trammel on these lines, so that the center lines of it may coincide with them; then adjust the sliders of the tracer, so that the distance between k and m may be equal to half the major axis, and the distance between 1 and in equal to half the minor axis, then by moving the bar around, the pencil in the slider will describe the ellipse.

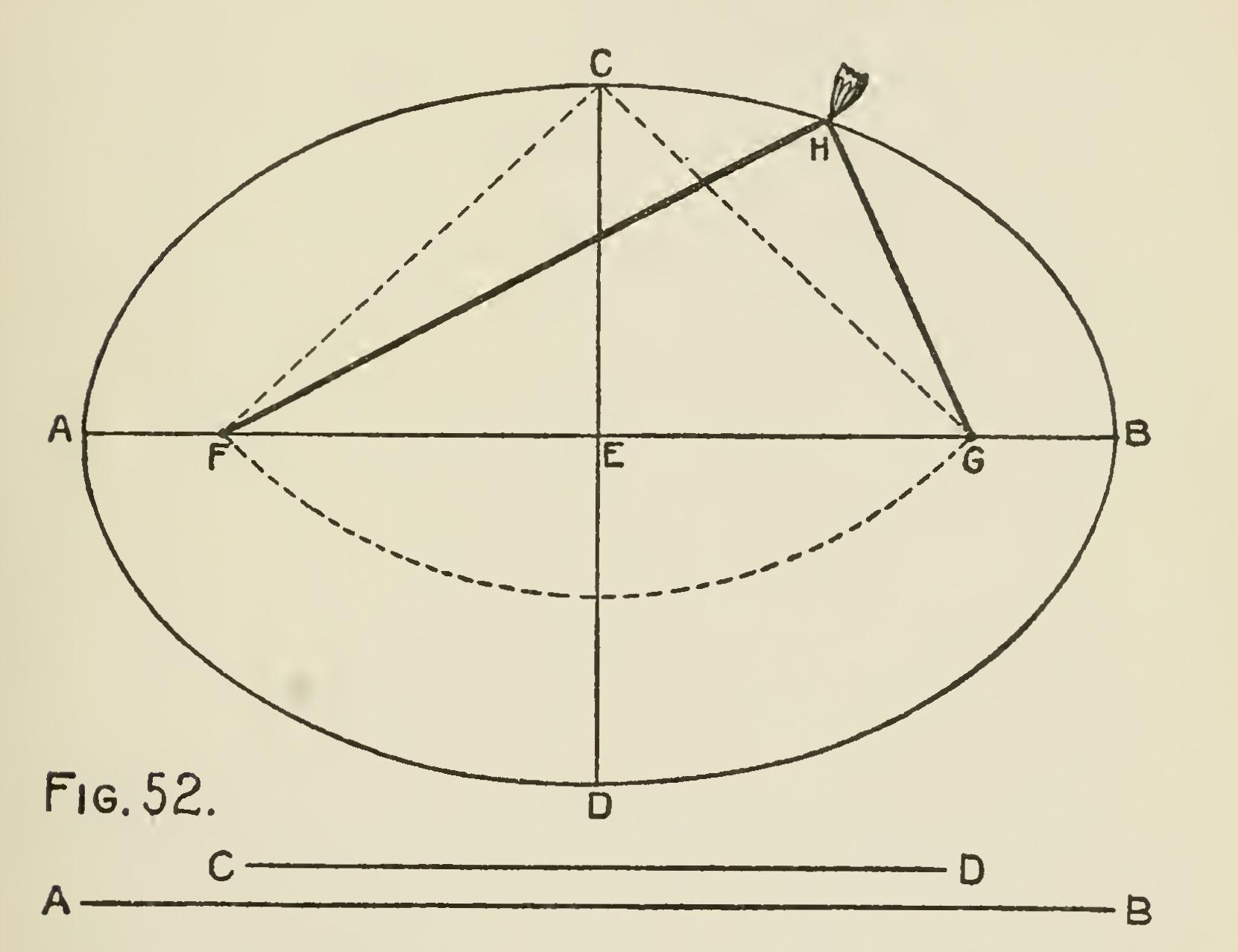

Problem ellipse may also be described by means of a string: Let AB (Fig. 52) be the major axis, and DC the minor axis of the ellipse, and FG its two foci. Take a string EFG and pass it over the pins and tie the ends together, so that when doubled it may be equal to the distance from the focus F to the end of the axis, B; then putting a pencil in the bight or doubling of the string at H and carrying it around, the curve may be traced. This is based on the well-known property of the ellipse, that the sum of any two lines drawn from the foci to any points in the circumference is the same.