Practical Carpentry

equal, line, ab, describe, fig, draw, radius and lines

Problem 4.—To trisect or divide a right angle into three equal angles: Let A B C (Fig. 26) be the given right angle. From the angular point B, with any radius, describe an arc cutting B A and B C in the points d and g; from the points d and g, with the radius Bd or Bg, describe the arcs cutting the arc dg in e and f ; join Be and Bf : these lines will trisect the angle A B C, or divide it into three equal angles.

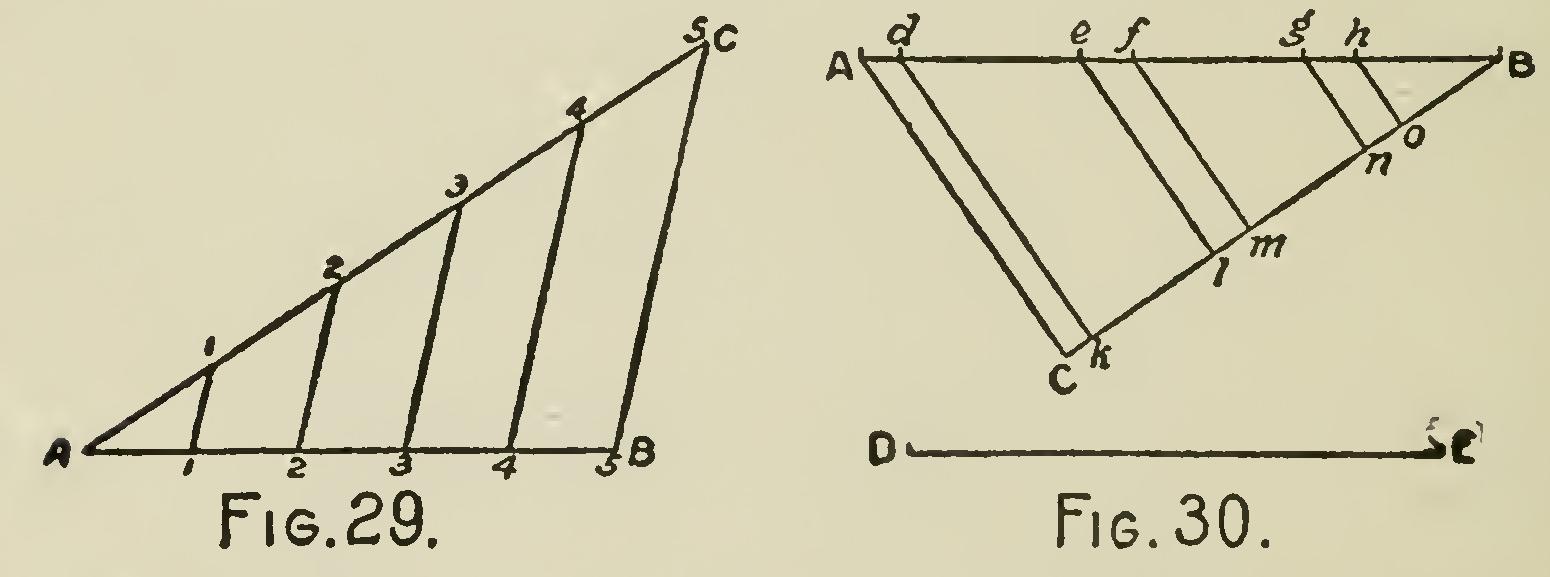

Problem 5.—From a given point C, in a given straight line A E, to erect a perpendicular: From the point C (Fig. 27), with any radius less than CA or CE, describe arcs cutting the given line A E in d and e ; from these points as centers, with a radius greater than Cd or Ce, describe arcs intersecting each other in f : join Cf, and this line will be the perpendicular required.

Problem 6.—To bisect a given straight line: Let A B (Fig. 28) be the given straight line. From the extreme points A and B as centers, with any equal radii greater than half the length of AB, describe arcs cutting each other in C and D: a straight line drawn through the points of inter section C and D, will bisect the line AB in e.

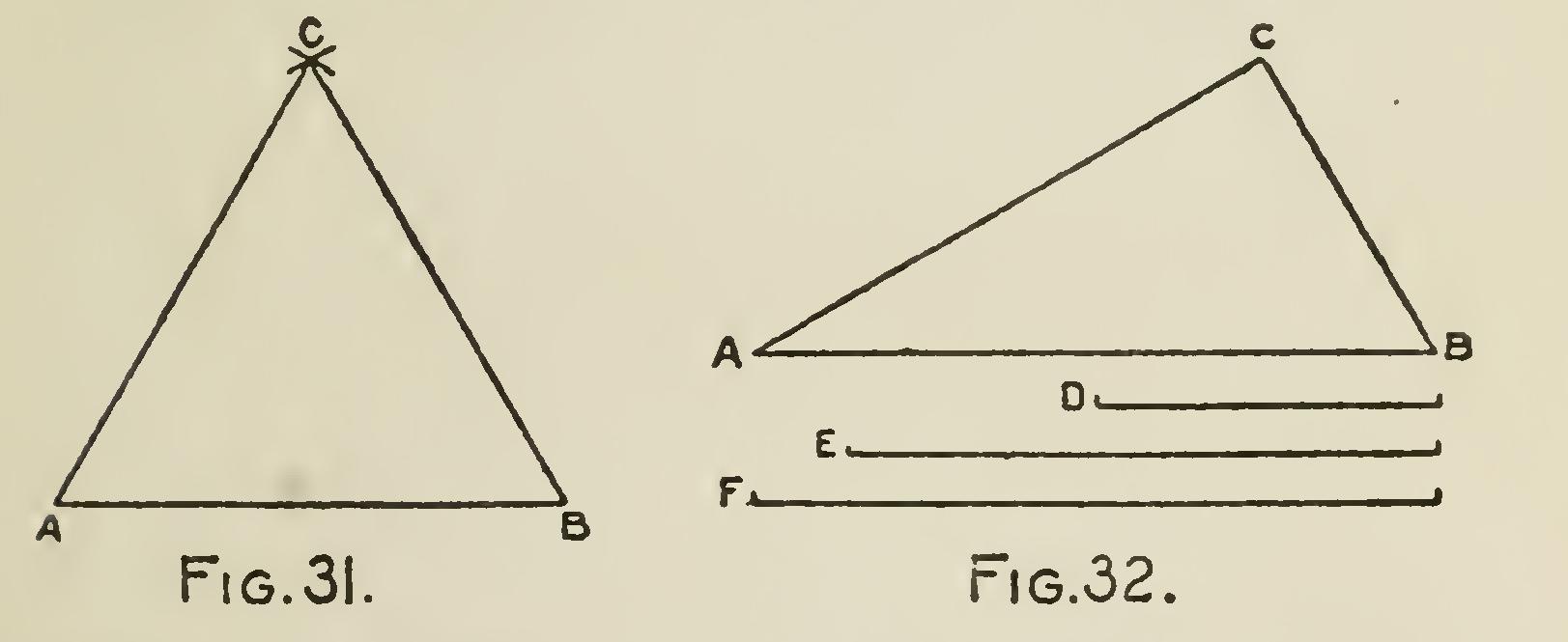

Problem 7.—To divide a given line into any number of equal parts: Let AB (Fig. 29) be the given line to be divided into five equal parts.

From the point A draw the straight line AC, forming any angle with AB. On the line AC, with any convenient opening of the compasses, set off five equal parts toward C; join the extreme points CB ; through the remaining points 1, 2, 3 and 4, draw lines parallel to BC, cutting AB in the corresponding points 1, 2, 3 and 4: AB will be divided into five equal parts as required.

There are several other methods by which lines may be divided into equal parts; they are not necessary, however, for our purpose, so we will content ourselves with showing how this problem may be used for changing the scales of drawings whenever such change is desired. Let AB (Fig. 30) represent the length of one scale of drawing, divided into the given parts Ad, de, ef, fg, gh and hB; and DE the length of another scale or drawing required to be divided into simi lar parts. From the point B draw a line BC-DE, and forming any angle with AB; join AC, and through the points d, e, f, g and h, draw dk, el, fm, gn, ho, parallel to AC; and the parts Ck, kl, lm, etc., will be to each other, or to the whole line BC, as the lines Ad, de, ef, etc., are to each other, or to the given line or scale AB. By this method, as will be evident from the figure, similar divisions can be obtained in lines of any given length.

Problem 8.—To describe an equilateral tri

angle upon a given straight line: Let AB (Fig. 31) be the given straight line. From the points A and B, with a radius equal to AB, describe arcs intersecting each other in the point C. Join CA and CB, and ABC will be the equilateral triangle required.

Problem 9.—To construct a triangle whose sides shall be equal to three given lines, F, E, D: Draw AB (Fig. 32) equal to the given line F. From A as a center, with a radius equal to the line E, describe an arc ; then from B as a center, with a radius equal to the line D, describe another arc intersecting the former in C; join CA and CB, and ABC will be the triangle required.

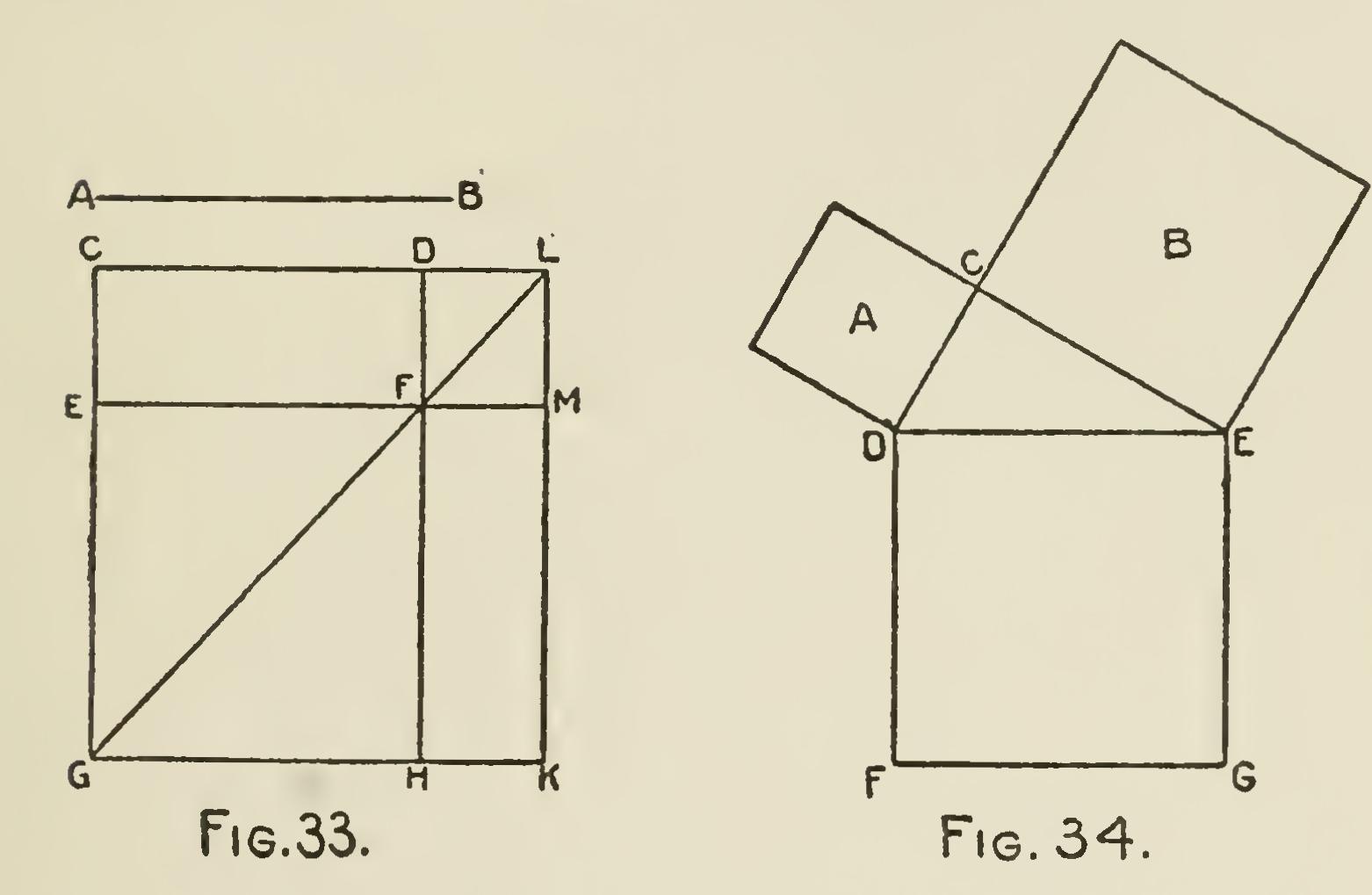

Problem 10.—To describe a rectangle or par allelogram having one of its sides equal to a given line, and its area equal to that of a given rectangle: Let AB (Fig. 33) be the given line, and CDEF the given rectangle. Produce CE to G, making EG equal to AB ; from G draw GK parallel to EF, and meeting DF produce in H. Draw the diagonal GF, extending it to meet CD produced in L ; also draw LK parallel to DH, and produce EF till it meets LK in M; then FMKH is the rectangle required.

Equal and similar parallelograms of any di mensions may be drawn after the same manner, seeing the complements of the parallelograms which are described on or about the diagonal of any parallelogram, are always equal to each other ; while the parallelograms themselves are always similar to each other, and to the original parallelogram about the diagonal of which they are constructed. Thus, in the parallelogram CGKL the complements CEFD and FMHK are always equal, while the parallelograms EFHG and DFML about the diagonal GL, are always similar to each other, and to the whole parallelo gram CGKL.

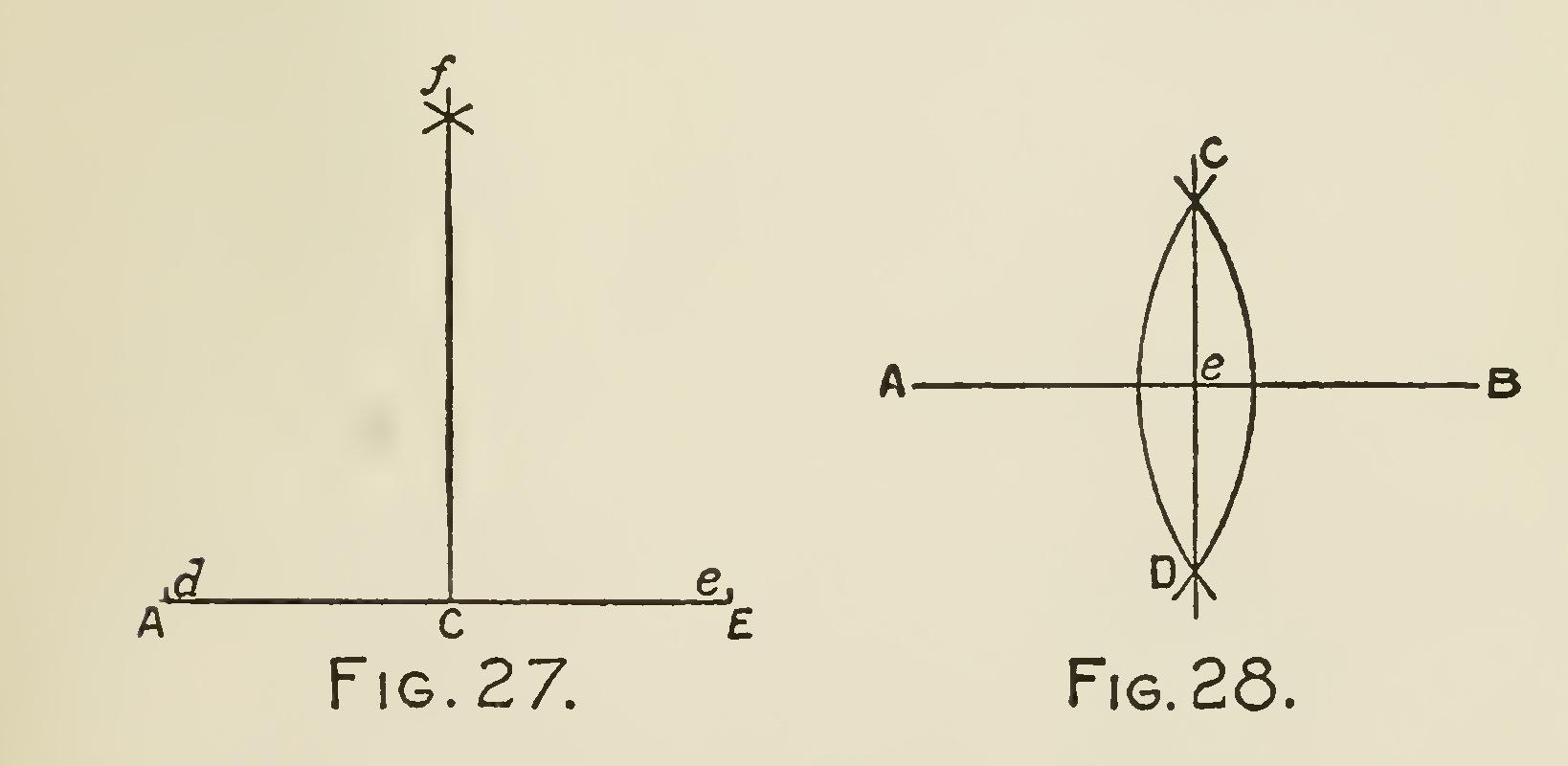

Problem 11.—To describe a square equal to two given squares: Let A and B (Fig. 34) be the given squares. Place them so that a side of each may form the right angle DCE; join DE, and upon this hypothenuse describe the square DEGF, and it will be equal to the sum of the squares A and B, which are constructed upon the legs of the right angled triangle DCE. In the same manner, any other rectilineal figure, or even circle, may be found equal to the sum of other two similar fig ures or circles. Suppose the lines CD and CE to be the diameters of two circles, then DE will be the diameter of a third, equal in area to the other two circles. Or suppose CD and CE to be the like sides of any two similar figures, then DE will be the corresponding side of another similar figure equal to both of the former.