Ii the Black Oak Group

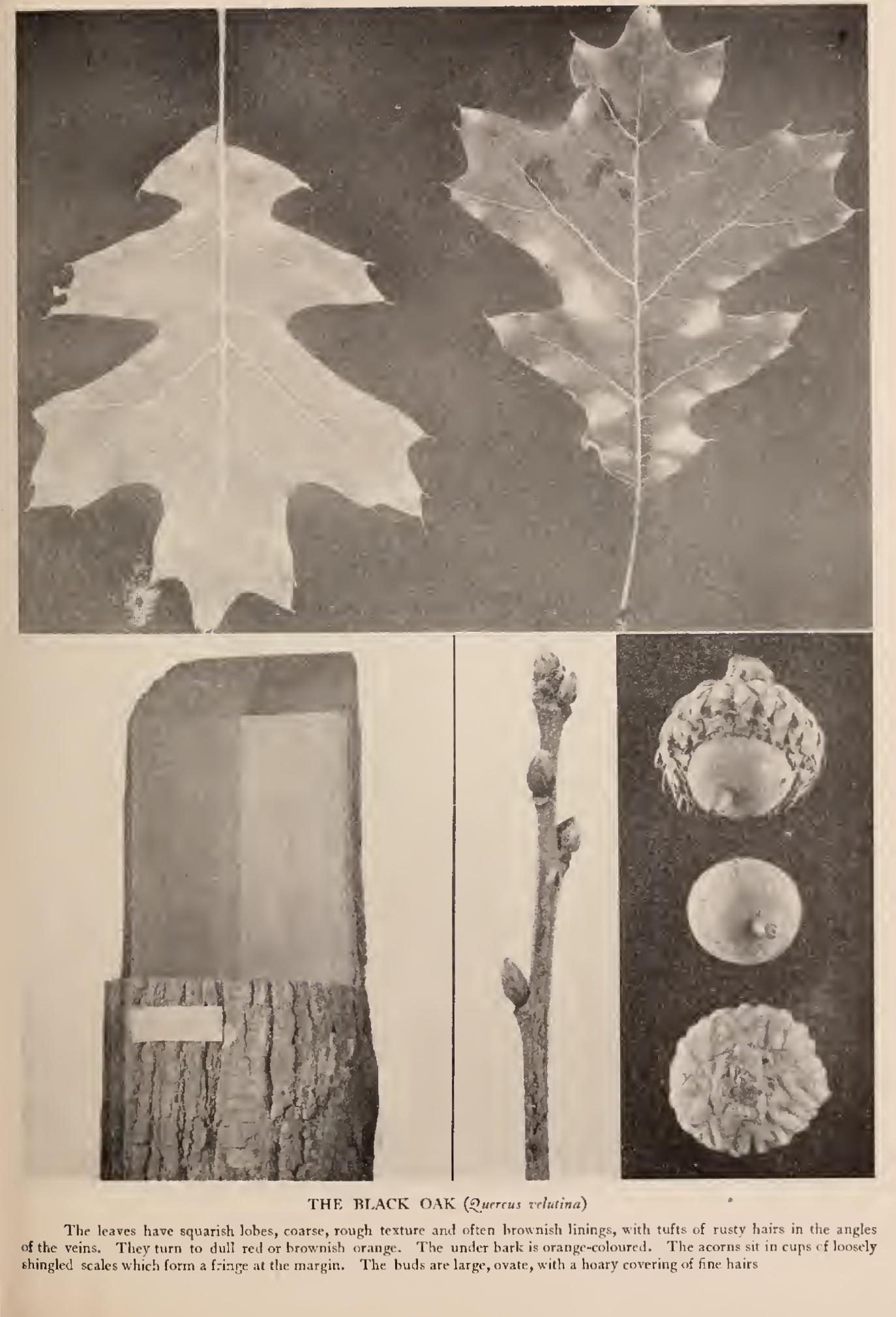

The coarseness of the leaves is one trait that distinguishes the species from the red and scarlet oaks, whose leaves it often imitates in form. Crumple a leaf of each in your hands. The red oak is intermediate between the leathery, harsh texture of the black, and the thinness and delicacy of the scarlet. The incisions in black oak leaves are rounded and deep, their bristly lobes point outward as often as they incline forward.

The bloom of black oak may be profuse or scant; the tree has its "off years." As the leaves lose their red the flowers take up the theme, and glow with ruddy stigmas and fringed tassels of stamens among the half-grown foliage. The lustiest shoots set acorns—sometimes a pair under each leaf. While the new ones are swelling and forming their little basal cups, on twigs a year older ambitious acorns of a larger growth are hurrying through their second summer to be ready to fall in October.

a large group which takes two years to ripen an acorn crop. As a rule, these trees always show half-formed acorns on their terminal twigs in winter. The white or annual-fruited oaks never carry any over; they ripen their fruits and cast them in the autumn. Black oaks have bristly pointed leaves; white oaks have only curved lines on their leaf margins. These facts are well worth remembering.

Most people know an oak "just by the looks of it." Ask them which oak it is, and they can't be sure. The bark of the black oak, with its orange lining, is the key to its name. The woodsman knows that this oak leads the country as the source of tan bark. Only the chestnut oak comes near it in percentage of tannin. Beside tannin, there is in the inner bark the yellow dyestuff called quercitron, which, before the discovery of aniline dyes, was largely used in the printing of calicoes. The yellow bark was dried, then ground, and the powdery citron-yellow colouring matter sifted out of it. Besides the yellow tints and shades, it gave, with the addition of salts of iron, various shades of grey, brown and drab.

Black oaks would doubtless be planted oftener for shade and ornament but that there are so many other beautiful oaks to choose from. In the wild they are noble ornaments to the natural landscape.

For my giant black oak on the hillside I have developed a kind of personal regard that surprises me. It is the result of getting acquainted with the tree at successive seasons of the year. It has taken on individuality. It ought to have a personal name, not merely its tribal cognomen. I have learned to read the answers to my questions. I have acquired, therefore, the rudiments of a new language—for tree language is a code of signs which anybody can learn. It is astonishing how much of inter esting personal and family history a tree will freely give in one year of friendly intercourse.

The Turkey Oak (Quercus Calesbcri, Michx.) grows most abundantly, and reaches 6o feet in height, in the high lands bordering bays and river mouths, along the coasts of South Carolina and Georgia. It follows the Gulf coast to Louisiana, but is rare west of Florida. It is an important fuel in the regions it inhabits, but is little known to lumbermen. Generally a small tree, 20 to 35 feet high, it may be distinguished from the Spanish oak by the greater size and breadth of its leaves, and by the teeth that generally adorn the tapering, triangular lobes. The leaves are thick and stiff; those of Spanish oak are thin and flexible.

The Spanish Oak (Quercus digitata, Sudw.), of the Southern States, is a distinguished-looking tree, with tall trunk and broad, open head covered with downy-lined leaves of peculiar forms. The lobes are elongated, often curved, sickle-like, rarely toothed, and separated by deep, wide sinuses. From this extreme they often vary widely, showing broadly obovate blades, often with no lobes at all. The leaves droop from the twigs, giving the tree an unique expression.

It is a pity that this tree is not hardy north of lower New Jersey and Missouri. It is one of the handsomest of shade trees. The old plantations of the South are likely to show a few aged Spanish oaks. There are two forms of the tree. Beside the upland type, a white-barked one abounds in swampy land. This tree has leaves very deeply cut, which turn a splendid yellow in autumn. Lumbermen count its wood nearly equal to white oak. The upland form yields far less durable timber.