Lamellibranchia

animals, system, gills, gastropoda, classification, class, species and shell

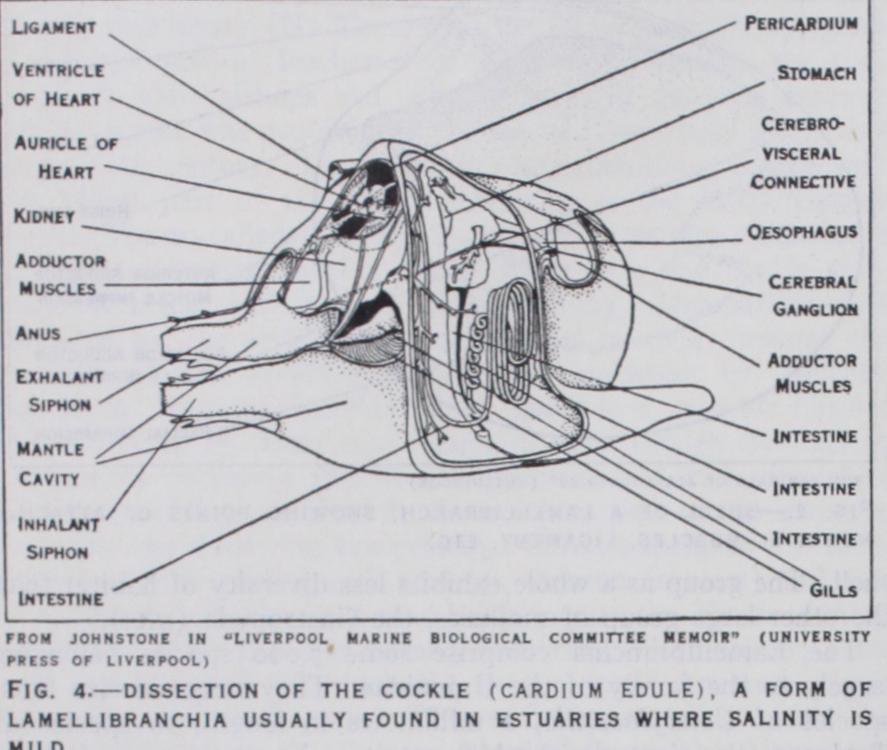

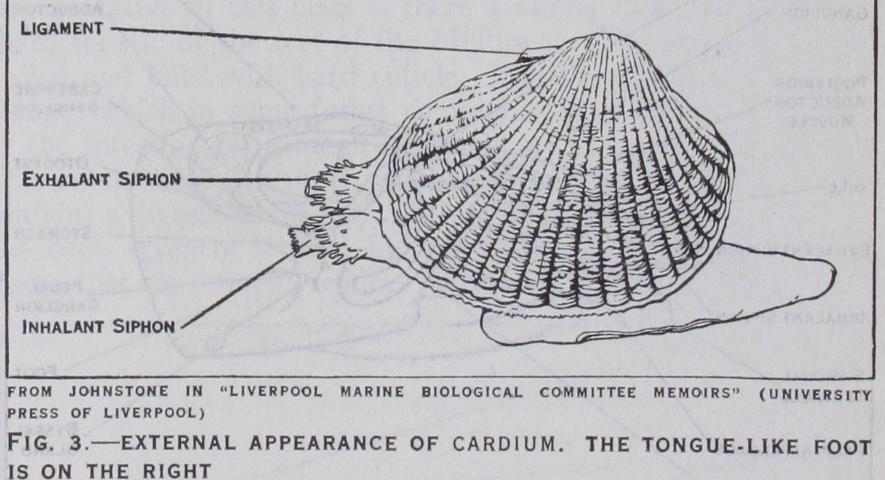

LAMELLIBRANCHIA, a group of aquatic invertebrate animals forming a class of the phylum Mollusca (q.v.). The most familiar examples of these animals are the oyster, the mussel and the cockle, and these popular names are sometimes given to various families and genera of the class. The name "bivalves" is also applied to these animals and a certain number of them are called "clams." The majority of the Lamellibranchia live in the sea, but a few families of the group have penetrated into brackish and fresh water. They are internally and externally symmetrical and are distinguished from other Mol lusca by the possession of a shell formed in two pieces (valves) which are articulated together by a system of interlocking teeth and joined in addition by a tough, cuticular ligament. They are fur ther distinguished by the rudi mentary development of the head and the presence of two symmetrical gills which are subject to very complex modification and, in addition to their normal respira tory function, play an important part in the process of feeding. The foot is usually well developed and modified for burrowing in sand and mud, and in many cases it secretes a tuft of adhesive threads (the byssus) by which the animal can anchor itself.

With very few exceptions the Lamellibranchia are sedentary animals which live buried in sand or mud and feed on minute plankton (floating plants and animals) and organic debris. A few groups have taken to burrowing in rock or wood and certain genera are permanently fixed down by the byssus or by one valve of the shell. The group as a whole exhibits less diversity of habitat than the other large group of molluscs, the Gastropoda (q.v.).

The Lamellibranchia comprise some 7,000 species belonging largely to the family of the Unionidae. They range in size from species of Condylocardia, a millimetre in length, to species of Tridacna (the giant clam) which attains a length of over 3ft., and Pinna. They have a considerable vertical range in the sea and are of almost universal distribution. Like the Gastropoda they first appear in the Lower Cambrian.

This class of molluscs has been united in the past with the Gastropoda and Scaphopoda to form a sub-phylum, the Prorhipid oglossomorpha. This arrangement emphasizes certain points in which those groups differ from the Cephalopoda and Amphineura. As far as the Lamellibranchia are concerned, however, the associa tion seems to exaggerate their resemblance with the Gastropoda and Scaphopoda, and to attach too little importance to the very marked specialization of this class. This specialization is apparent

in the most primitive members of the Lamellibranchia and seems to suggest very early divergence from the rest of the Mollusca.

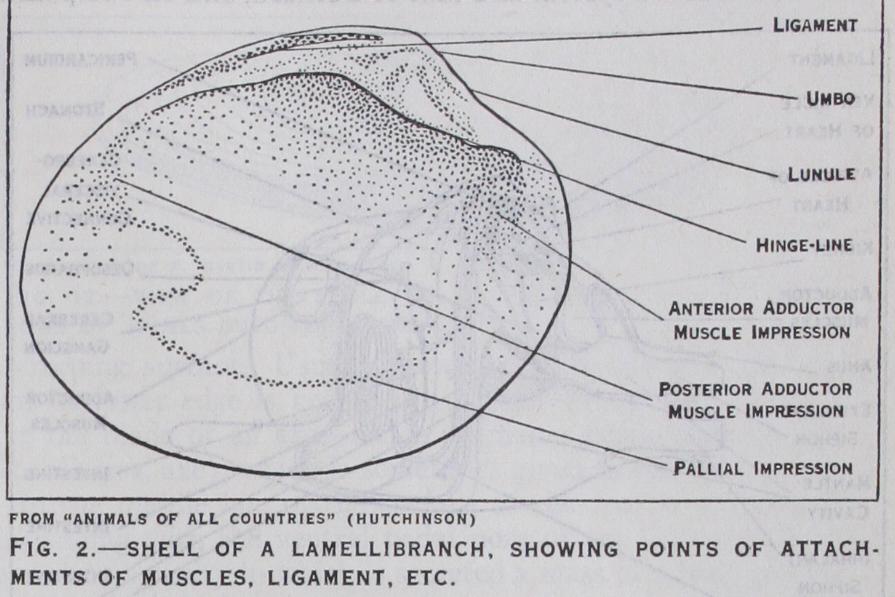

One of the outstanding features of the Lamellibranchia is the structural uniformity which is found in many of their internal and external parts. This has made it peculiarly difficult to distinguish satisfactory subdivisions of the group and its classification has, as a result, been a source of much controversy in the past. Palae ontologists and the students of living molluscs have differed as to the basis upon which the main subdivisions should be established. The main groups recognized by zoologists depend upon the struc ture of the gills. The latter are not preserved in fossil remains and, as a result, the palaeontologist has had recourse to the shell and in particular to that part of it which alone is susceptible to system atic treatment, viz., the hinge-line and the teeth situated thereon The schemes of classification produced by these different methods are somewhat different ; but they can in some cases be reconciled, as the divisions proposed contain more or less the same families. Thus the classification proposed by Pelseneer and based on the gill structure is very largely equivalent to that suggested by Dall who used the hinge-line as a basis. More radical differences are found between Pelseneer's system and that of Bernard, and on two points the zoologist has some difficulty in accepting the latter: (I) Sev eral important features (the structure of the foot, coelom and gills) indicate that forms such as Yoldia and Solenomya (Proto branchia of Pelseneer) are the most primitive Lamellibranchs; but Bernard places them as a suborder of his Pleurodonta appar ently more specialized than the Mytilidae, Pectinidae, etc., and associates with them forms otherwise more specialized such as the Arcidae and Pectunculidae. (2) Nothing seems more certain than that the special bionomic and structural characters of the Septi branchia are of basic importance. Yet Bernard puts them in a Heterodonta subdivision without any special distinction. It is far from desirable to ignore the palaeontologist's point of view in this question, especially as it involves a study of the embryological development of the hinge; but on the whole it seems better, until a more satisfactory system is produced, to accept the zoological classification. Though it is primarily based upon the structure of the gills, it takes other organs into account.