Lamellibranchia

food, animals, plankton, debris, holes, burrow, material and clams

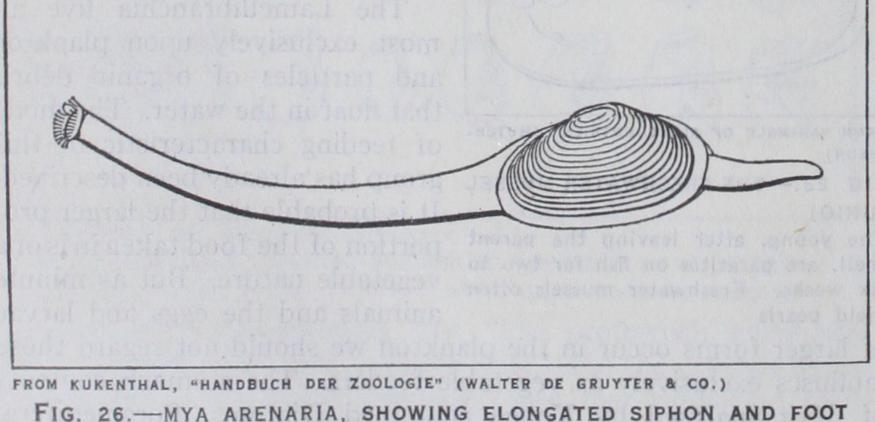

Most burrowing forms keep within a few inches or less of the surface, the distance to which they burrow being largely deter mined by the lengths of the siphons, for, as a rule, the orifices of both the exhalant and inhalant siphons are kept more or less at the surface. Thus Mya arenaria, which has rather long siphons, lives about six or eight inches below the surface. Weymouth states that the pismo clam (Tivela stultorum) of California usually lies with the hinge-line directed towards the oncoming surf and the open edge of the valves towards land. Forms which cannot readily orientate themselves in the unstable bottom of the open beach are found in situations where they can form a semi-permanent burrow and the substratum is more solid. Such conditions are realized in the quieter reaches of slow estuaries or in deep bays where the mud is less liable to disturbance. It is here that Mya, Scrobicularia, Cardium, Macoma are found in the northern hemisphere.

There are a good many lamellibranchs which burrow into hard material and become adapted to this existence. Pholas, Litliodo mus, Saxicava, Clavagella, etc., live in holes excavated either by acid secretions or the shell itself. In certain places on the south coast of England the flat slabs of chalk debris at the foot of cliffs are riddled by the holes made by Pholas. Teredo (q.v.) and Xylotrya burrow in submerged timber in which they excavate long passages and such wood may often be honeycombed with these holes. The name "ship worm," which is given to Teredo and its allies, indicates that in the past wooden ships were very prone to the attacks of this mollusc (see "Economic Im portance").

The Lamellibranchia live al most exclusively upon plankton and particles of organic debris that float in the water. The mode of feeding characteristic of this group has already been described.

It is probable that the larger pro portion of the food taken in is of a vegetable nature. But as minute animals and the eggs and larvae of larger forms occur in the plankton we should not regard those molluscs exclusively as vegetable feeders. The stomach contents of Mya analysed by Yonge contained Diatoms, Foramenifera, minute (probably larval) bivalves, Ostracods and other small Crus tacea, spores and eggs of various kinds, sponge-spicules, etc., though "the largest mass of material consisted of small sand grains." There were also fragments of organic debris, e.g., strips of Algae. The Septibranchia are usually regarded as carnivores.

Living at great depths from which plants are normally excluded by the absence of sunlight they obviously cannot obtain living plant tissue for food. The very profound modification of the gills deprives them of the apparatus for fine sorting found in other classes. Lastly their intestine is very short and of a carnivorous type. As a matter of fact they must subsist very largely on animal plankton and coarse particles of animal carrion, though in all probability a good deal of vege table debris finds its way at least into the less profound depths of the oceanic abyss. Among those lamellibranchs which bore into the solid material the shipworm has recently been shown to be practically inde pendent of plankton for food and to live upon the wood into which it bores.

The chief defences of the Lam ellibranchia against enemies are the valves of the shell and the bur rowing habit. Without this pro tection such slow-moving animals deprived of weapons of active defence would be entirely at the mercy of more aggressive en emies. As it is they are preyed upon by a great variety of animals, some of which rely almost entirely on them for food and have developed special modes of attack. Various sorts of whelk (Buc cinum, Purpura, Nassa) and Natica drill holes through the valves by means of an acid secretion of the alimentary canal and the radula and by the aid of the ex tensible proboscis feed on the animal contained therein. Sca phander and other Gastropoda, which have gizzards armed with masticatory plates, swallow small bivalves whole and crunch them up in the gizzard. Birds, fish and other aquatic animals deal with them in the same way. Walruses feed on clams of various kinds which they are said to dig up with their tusks. Fishery investigations have em phasized the importance of Lam ellibranchia as an element in the food of edible fishes and the work of Davis on the bottom fauna of the Dogger Bank, where the small clams Spisula subtruncata and Mactra stultorum pre dominate over all other large invertebrate animals of the sea bot tom, shows how in a particular area the Lamellibranchia are the most important constituent of the food. Davis has shown that Spisula subtruncata occupies rather local patches on the south end of the Dogger Bank. These are of vast extent and dense popu lation, one such patch having an area of 7oosq.m. and probably carrying a population of 4.500,000,000,00o clams.