Lamellibranchia

found, species, water, live, marine, genera and animals

The majority of Lamellibranchia live in the sea and the orders Protobranchia, Filibranchia and the specialized Septibranchia are almost exclusively marine in distribution. Among the Filibranchia Scaphula lives in the rivers of India and of the Eulamellibranchia the Unionidae, Cyrenidae, Etheriidae, Cycladidae, Mutelidae and a few isolated genera such as Erodona are inhabitants of fresh water. The Unionidae, which are most plentiful in America, are one of the largest families of freshwater animals.

There are in addition a certain number of forms which consti tute a population intermediate between the truly marine and freshwater fauna. These are found in the estuaries of large rivers and in tidal ditches and lagoons. The cockles (Cardium) seem to thrive in a salinity midway between that of the sea and of fresh water and are usually found in estuaries. Other forms which are "euryhaline" (i.e., tolerate a wide range of salinity) or require intermediate conditions are found among the Arcidae, Limno cardiidae, Mytilidae, Scrobiculariidae, Macoma, etc.

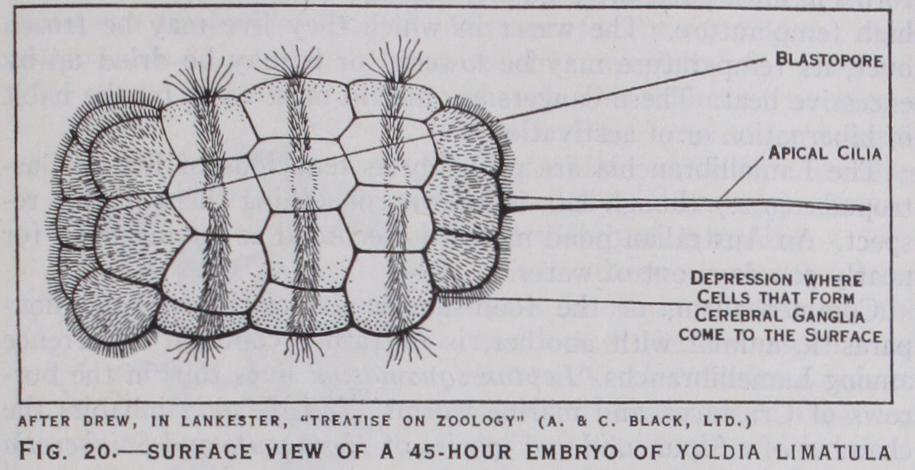

The marine Lamellibranchia are widely distributed and are found in all seas of which the faunas are known. As in all other groups of marine animals certain areas are characterized by the exclusive occurrence of certain genera or of the majority of the species of certain genera. Thus Mya, Y oldia and Astarte are found very largely in Arctic seas. As regards the vertical distribu tion of Lamellibranchs it may be said that Solen, Cardium, Ostraea and Tellina, for example, live principally in shallow water. The Septibranchia as a whole inhabit deep water and with them are found species of Pecten, Abra and Callocardia. Species of the two last-named genera have been found at a depth of 2,900 fathoms, the greatest depth at which a lamellibranch has been recorded.

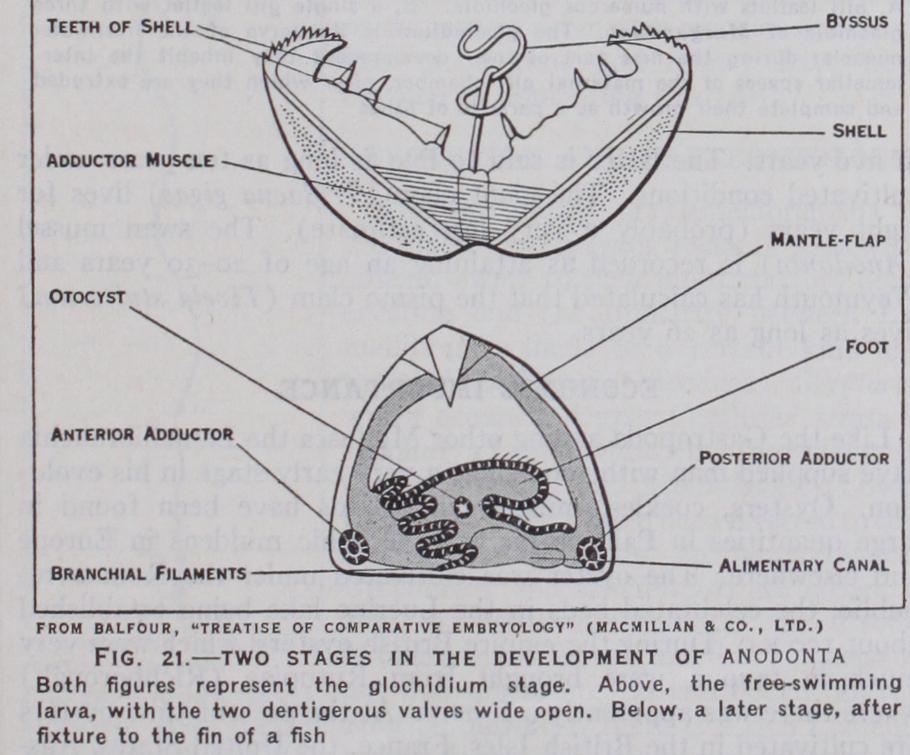

Freshwater Lamellibranchia have been found in all the great river systems of the world. The larger forms (Unio and Anodonta) tend to keep to rivers, lakes and large ponds; but the smaller forms (Pisidium, Cyrena, etc.) occur in pools, ditches, streams and marshes. As examples of regional localization we may cite the Etheriidae and Spatha which are exclusively found in Africa, where Corbicula is also well represented ; and Scapinda and Paral lepipedum which are peculiar to India. The dispersal of marine lamellibranchs is mainly effected in the free-swimming larval stage during which they drift about in currents. Such freshwater

forms as are parasitic in the larval stage (vide ante) no doubt owe their dispersal to the fish on which they live. Others may be car ried from one river or lake to another by birds or are transported by water beetles ; examples of Sphaerium and Pisidium have been found clinging by their valves to the legs of those animals.

The habitats of the individual species of a genus tend either to be more or less distinct or to overlap to some extent. Thus in a survey of a certain part of the English Midlands Pisidium caser tanum is reported as occupying a great variety of habitats and P. obtusale is only found in ditches and marshes. Johansen in his survey of Randers Fjord in Denmark found that Anodonta cyg nea ranged into 2-3 promille salinity and A. complanata was re stricted to .2-6 promille. Nevertheless we are far from knowing with certainty to what extent the members of species diagnosed from their structural characters occupy identical habitats over the whole of their range. (See GASTROPODA and SPECIES.) Habits, Food, etc.—The Lamellibranchia are for the most part sedentary animals and their locomotor activities are in the main specialized for making way through the semi-solid medium con stituted by sand and mud rather than for rapid progression in less restricted circumstances. A few, indeed, are capable of quick darting movement through the water and all the more sedentary forms do not live actually below the surface of the bottom.

Nevertheless a large proportion of them are burrowers and although their range may be limited and their rate of progression slow, we should not overlook how much effort is expended and what activity must be necessary in order to make way through sand and mud. Moreover, in those forms which live on the open coast where sand is continuously being washed away or bedded up, especially in rough weather, considerable exertion is necessary to keep the animal in the right position for feeding and to pre vent it from being either buried or washed out and flung high up the beach. In several families this danger is averted by perma nent fixation to some solid object (rocks or stones) by means of the byssus or, in more specialized forms, of one valve of the shell.