Lamellibranchia

valves, shell, mantle, mass, visceral, siphons, orifice and edges

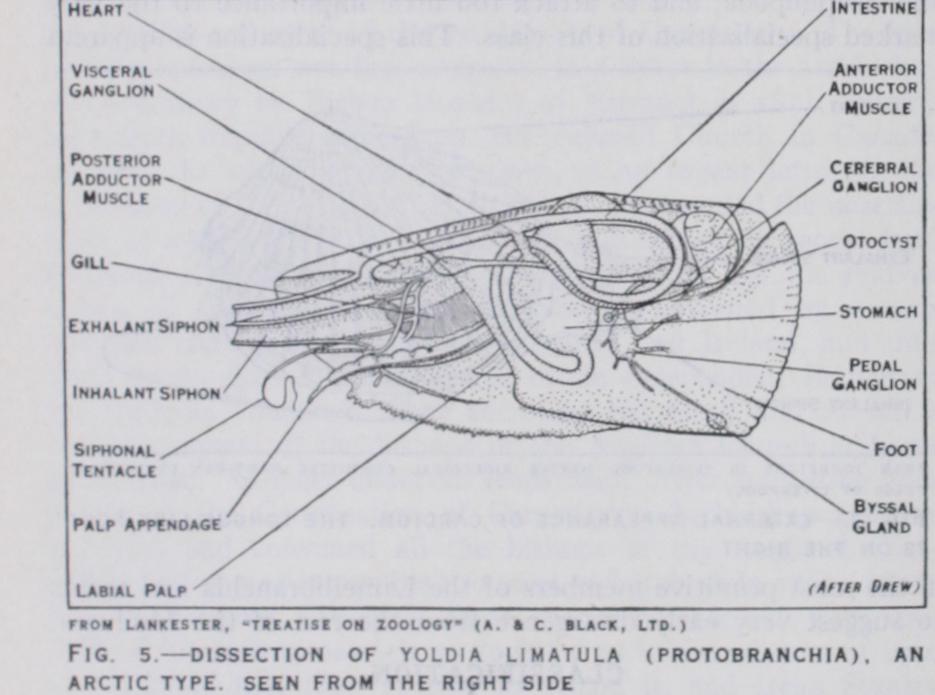

The body of a Lamellibranch is divisible into three main areas— the visceral mass, the mantle and the foot. There is no specially differentiated head such as is found in other molluscs. The animal is bilaterally symmetri cal and the main axis is occu pied by the visceral mass. The mouth is situated at the ante rior end of the latter and, though it is provided with lips which are generally continued on each side as lobes (labial palps), this area is not marked off from the rest of the body and except in Nucula and Poromya, is not furnished with sense organs and tentacles.

The visceral mass is covered over by a sheath of integument, the mantle, which hangs down on each side like the skirt of a coat.

Between the free part of the mantle on each side and the visceral mass is the mantle cavity. The foot projects as a highly muscular prominence from the under side of the visceral mass.

The mantle and its derivatives are in a sense the most important feature of Lamellibranch organization and as such its role is corn parable with that of the mantle of the Decapod Cephalopoda (q.v.). Not only does it secrete the shell, but its edges are pro duced into inhalant and exhalant siphons, and its derivatives, the gills, perform respiratory, nutri tional and incubatory functions.

The shell first appears in the embryo as a single structure. In the course of subsequent develop ment two separate calcified plates are secreted by the right and left areas of the shell-gland. With very few exceptions these valves are joined together by a series of interlocking teeth which project from the inner dorspl border of the valves (hinge-line).

The arrangement, shape and development of these teeth are variously differentiated and af ford, as has been shown, a basis of classification. Munier Chalmes and Bernard have devised a method of representing the different types by means of formulae and symbols. The two valves are additionally joined by a chitinous ligament which is a persistent rudiment of the larval shell. The action of the ligament is to pull the top edges of the two valves together so that the lower edges "gape" and expose the animal within.

The gaping of the valves is counteracted and the valves are closed by the contraction of strong adductor muscles. These muscles. which are usually two in number (anterior and posterior posed transversely to the main axis of the body and they join the mantle-lobes to the valves on each side. By contraction of these muscles the resistance of the hinge is overcome and the valves are closed. Thus, as long as the valves are closed, the muscles are in a state of tonus and when this is relaxed the valves are separated.

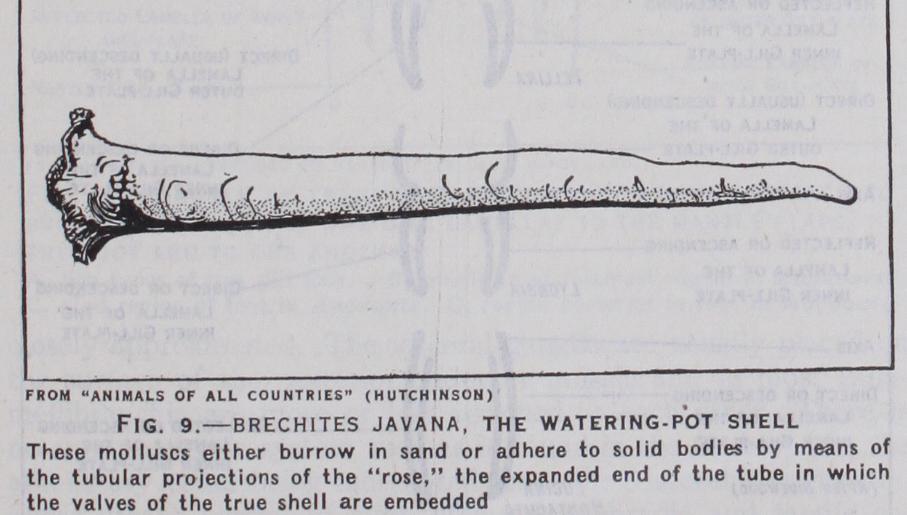

The shell varies very considerably in shape. In some genera the two valves are unequal in size and of a different shape (Pecten, Ostraea), and some forms are permanently fixed in the sea-bottom by the adhesion of one valve to the latter (Chama, Spondylus). In certain species of Pinna, Ano donta, etc., the valves are fused along the hinge-line. In Ensis (the razor shell) the shell is long and tubular ; in Brechites and Teredo (the shipworm) it is re duced to a rudimentary shell. A variety of ornamentation is formed by the interruption of the growth-lines of the shell by ribs radiating from the umbo (apex of the dorsal border) and by development of spines and scales.

As in the Gastropoda the man tle may become reflected over the surface of the shell (Galeommidae) and finally in Scioberetia and a few other genera it completely covers the shell.

The mantle hangs down on each side of the visceral mass as two loose folds and in the most primitive Lamellibranchia the ventral edges of their folds are entirely free and unattached (Nucula, Arca, etc.). In all other members of the class the two lobes of the mantle are united with each other at one or more points below the ventral surface of the visceral mass.

In a large number of forms there is one junction only. This is at the posterior end of the animal and it forms an aperture oppo site to the anus. This is known as the exhalant orifice and serves for the passage of faeces and stale water from the mantle cavity to the exterior. Among a second large group of families there is a second junction close to the first. Three apertures are thus formed in the mantle-edge : the posterior or exhalant aperture (already described), a median or inhalant aperture (by which water is drawn into the mantle cavity) and a larger anterior orifice from which the foot projects (pedal orifice). A fourth orifice is produced, e.g., in certain of the family Solenidae, by a third fusion of the mantle-edges. The exhalant and inhalant orifices are in many genera prolonged as tubes or "siphons." Elongate siphons are characteristic of burrowing forms as they enable the mollusc, when burrowing below the surface, to maintain com munication with the water upon which it depends for food and oxygen and also to get rid of its waste products. Forms like Cum mingia, Pholas, Mactra have very long siphons, twice or three times as long as the shell. In Teredo the siphons form the larger part of the total bulk and secrete a calcareous tube. Similar large siphons which secrete a calcareous sheath are seen in Clavagella.