Miscellaneous Rules

circle, square, diameter, blade, tongue, bevel and center

To Find the Circumference of a Circle

with the square and bevel proceed as follows: Set the bevel to 7 on the tongue and 22 on the blade; move the bevel to the given diameter on the tongue of the square, and the approximate answer will be found on the blade. When the diameter is wanted the operation is simply reversed, that is, we put the bevel on the blade and look on the tongue of the square for the answer.

To Find Side of Greatest Square in a Circle.— If we want to find the side of the greatest square that can be inscribed in a given circle, when the diameter is given, we set the bevel to 8 on the tongue and 12 on the blade. Then set the bevel of the diameter on the blade, and the answer will be found on the tongue.

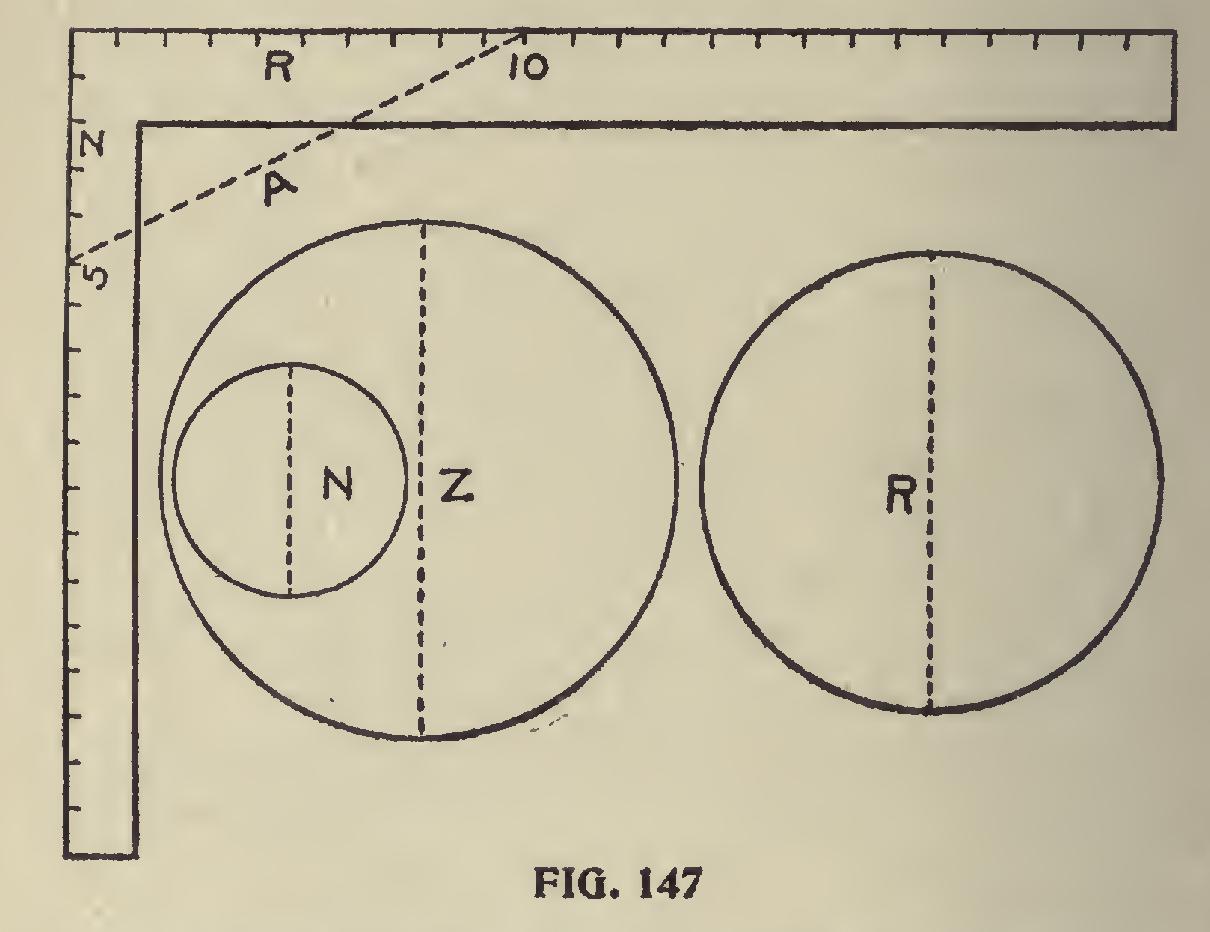

To Determine Proportions of Cylindrical Bodies. —In Fig. 147 is shown a method to determine the proportions of any circular presses or other cylindrical bodies, by use of the square. Suppose the small circle, N, to be five inches in diameter and the circle R is ten inches in diameter, and it is required to make another circle, Z, to contain the same area as the two circles N and R. Meas ure line a, on the square, from five on the tongue to ten on the blade, and the length of this line A from the two points named will be the diameter of the larger circle Z. And again, if you want to run these circles into a fourth one, set the diame ter of the third on the tongue of the square, and the diameter of Z on the blade, and the diagonal will give the diameter of the fourth or largest circle, and the same rule may be carried out to infinite extent. The rule is reversed by taking the diameter of the greater circle and laying diag onally on the square, and letting the ends touch whatever points on the outside edge of the square. These points will give the diameters of two circles, which combined, will contain the same area as the larger circle. The same rule can also be applied to squares, cubes, triangles, rectangles, and all other regular figures, by taking similar dimensions only; that is, if the largest side of one triangle is taken, the largest side of the other must also be taken, and the result will be the largest side of the required triangle, and so with the shortest side.

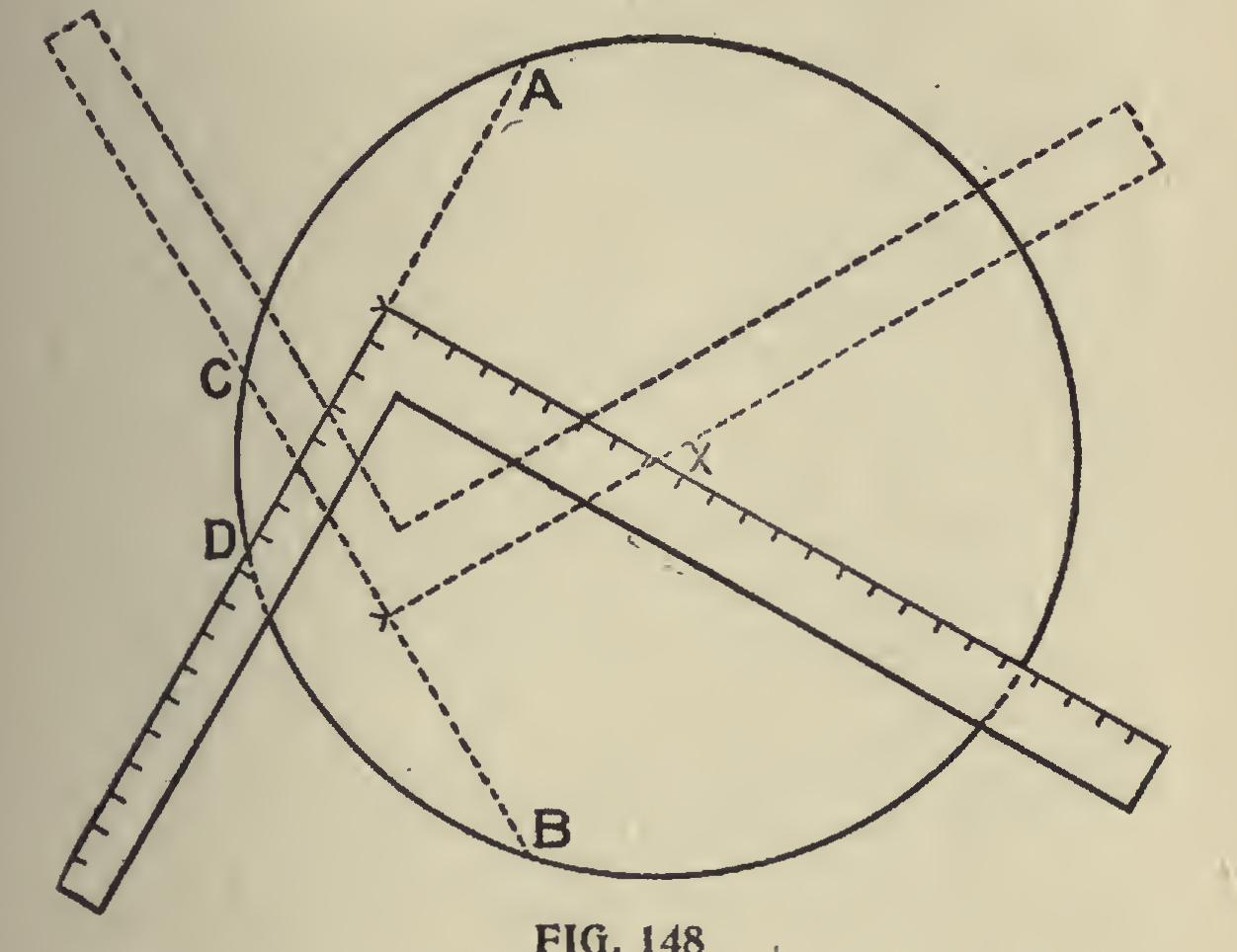

To Determine Center of a Circle.

In Fig. 148 we show how the center of a circle may be deter mined without the use of compasses; this is based on the principle that a circle can be drawn through any three points that are not actually in a straight line. Suppose we take A B C D for four givenpoints, then draw a line from A to D, and from B to C; get the center of these lines, and square from these circles as shown, and where the square crosses the line or where the lines intersect, as at X, there will be the center of the circle. This is a very useful rule, and by keeping it in mind the mechanic may very frequently save himself much trouble, as it often happens that it is neces sary to find the center of the circle, when the com passes are not at hand.

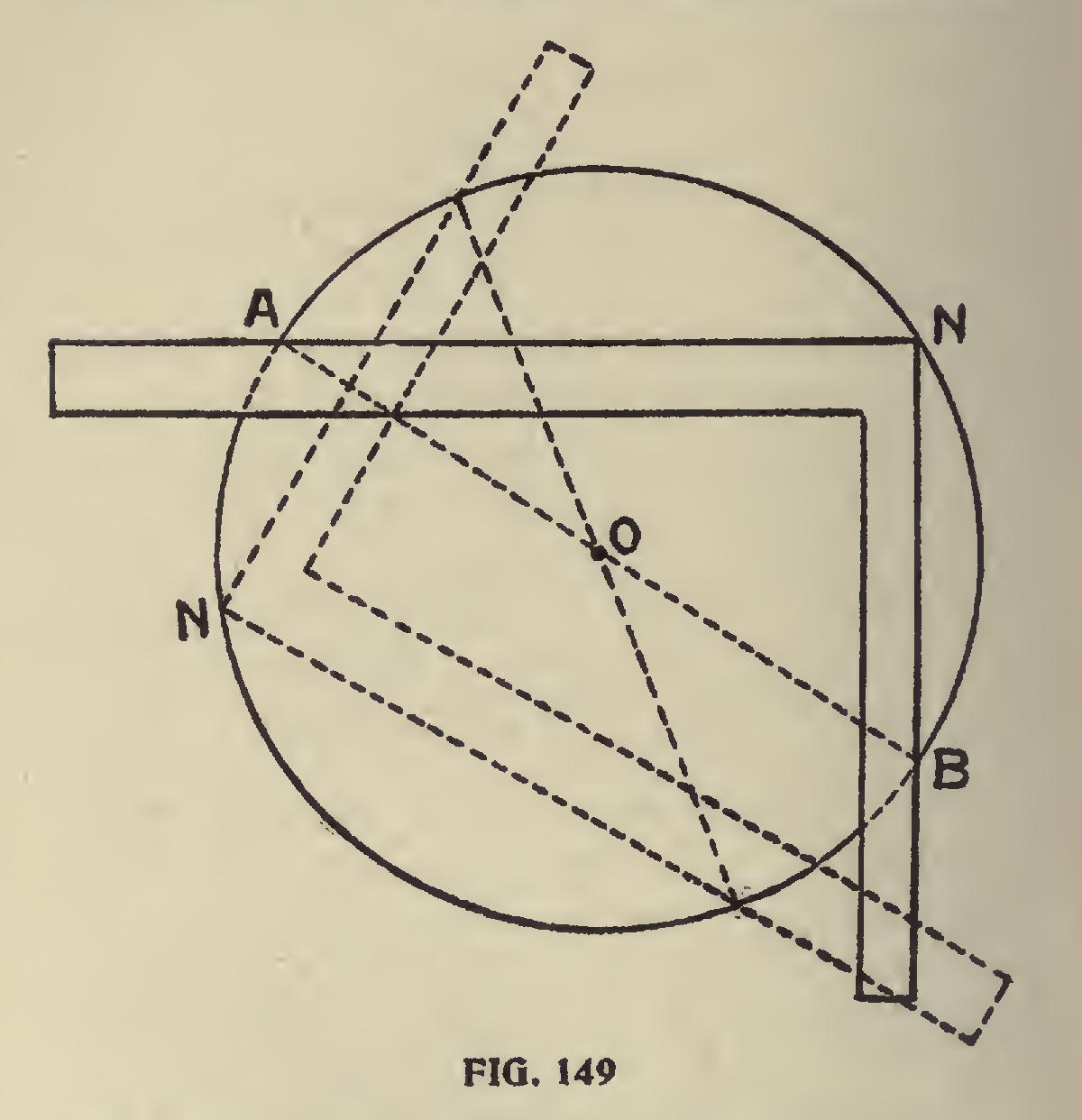

Another Quick Method

of finding the center of a circle by means of the steel square is shown in Fig. 149. Let N N, the corner of the square, touch the circumference, and where the blade and tongue cross it will be equally divided; then move the square to any other place and mark in the same way and straight across, and where. the line crosses A, B, as at 0, there will be the center of the circle.

To Find a Square of Equal Area to a Given Circle, we set the bevel to 91 inches on the tongue, and 11 inches on the blade; then move the bevel to the diameter of the circle on the blade, and the answer will be found on the tongue. If the circumference of the circle is given, and we want to find a square containing the same area, we set the bevel to 51- inches on the tongue and 19i inches on the blade To Obtain Circumference of Circle of Given Diameter.—There are quite a number of methods of obtaining approximate proportions of the dia meter of circles to their circumferences. The true proportion, or. as it is sometimes expressed, the squaring of the circle, is one of those feats, like the discovery of perpetual motion, and is as far from being accomplished as ever. At any rate, it makes but little difference at this time to the operative mechanic, whether the circle can be squared or not, so long as he can get near enough to the truth to satisfy the requirements at hand satisfactorily, and to aid him in this, the following method is shown of obtaining the circumference of circles when the diameter is given, by use of the square. Of course, as shown in the cut the rule will apply to circles of any reasonable dimen sions.