Miscellaneous Rules

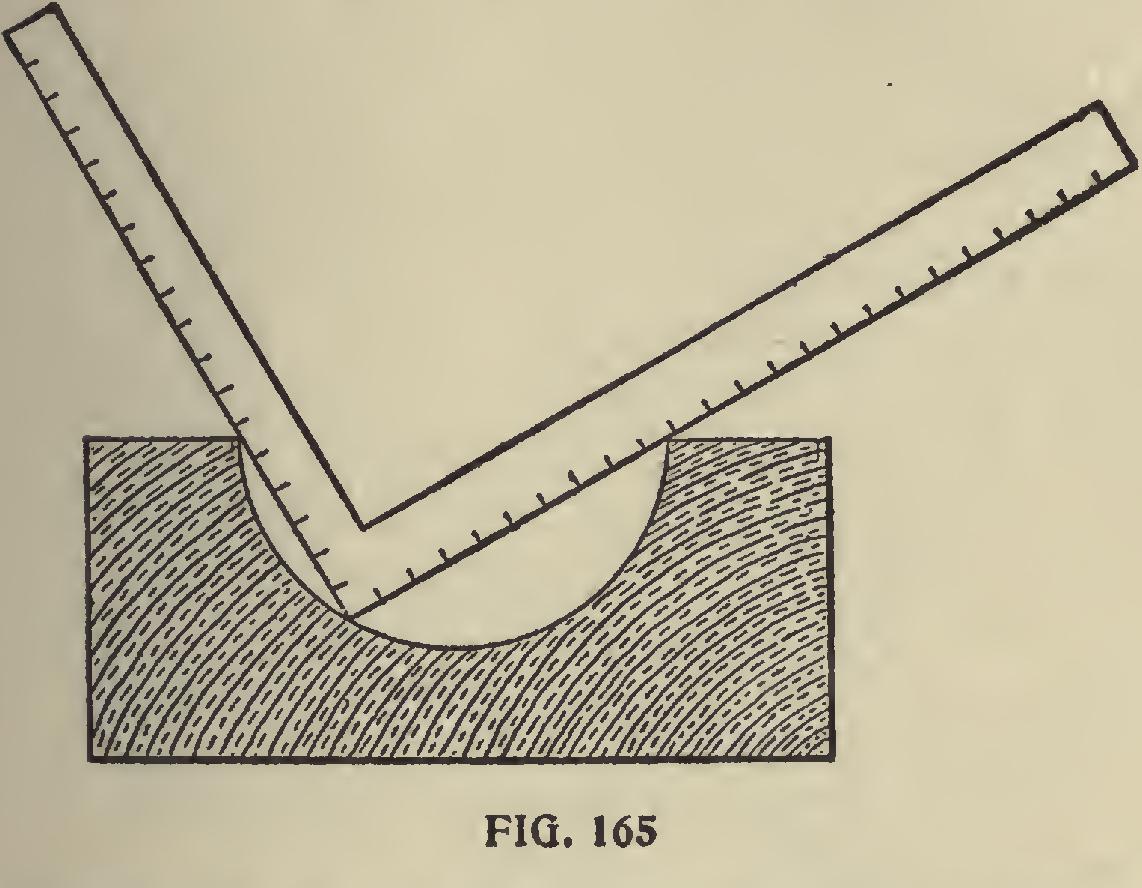

square, blade, tongue, line, fig, lines, equal and length

In this instance the square may be used as a tem plet, and the advantages of it in such cases are that it may be used in any sized semicircular groove, thus saving a multiplication of templets. This principle may be extended further, as it is equally applicable to a hollow hemisphere as to a hollow semicylinder, which makes the know ledge of this fact of great value to wood or metal turners, as it can be easily seen that a hollow hemisphere must be nearly true if the cutter or heel of. the square touches every point, and the blade and tongue lie on the exact diameter. The operator can apply this principle to many cases, if he is at all ingenious.

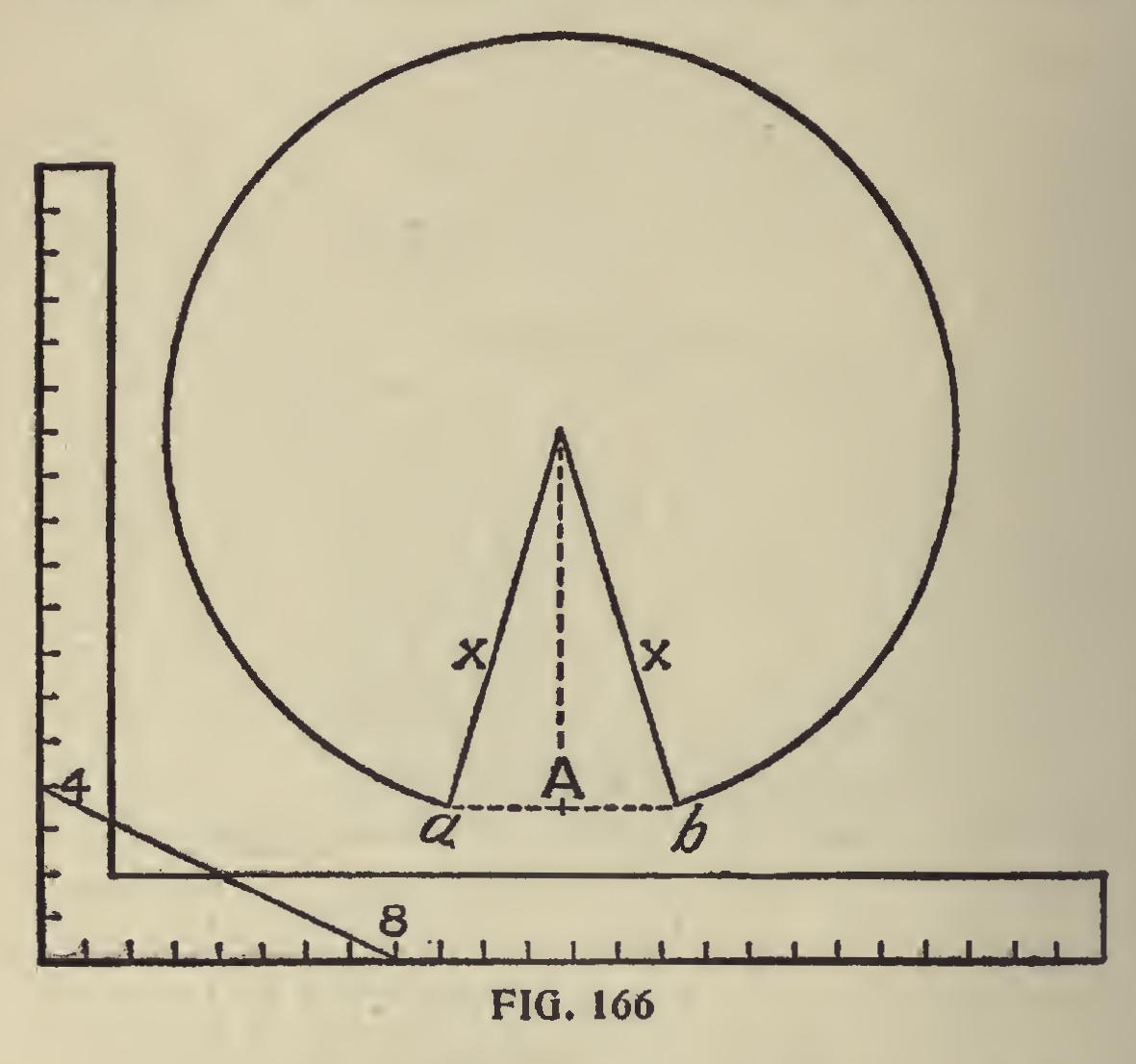

To Cut for Pitched Covers.—Here is a little problem that may come into use on many occas ions: Suppose we want to cut a piece of sheet metal, paper or thin wood so that it may form a cone, or a cover for a vessel of some sort; say the pitch or height at center is to be four inches, and the diameter of the base sixteen inches. Lay off the pitch on the tongue and half the diameter on the blade. The diagonal, from 4 to 8, as shown in Fig. 166, gives half the diameter of the circle, to which set your compasses. Describe a circle as at Fig. 166, draw a line from the center as shown, square off from A, on each side three tenths of the radius, ending at a, and b. The gore left requires to be removed, then when the edges X X are brought together the cone is com plete.

The Circumference of an Ellipse or Oval is found by setting 5 and five-eights on the tongue and 8-1 inches on the blade; then set the bevel to the sum of the longest and shortest diameters on the tongue, and the blade gives the answer.

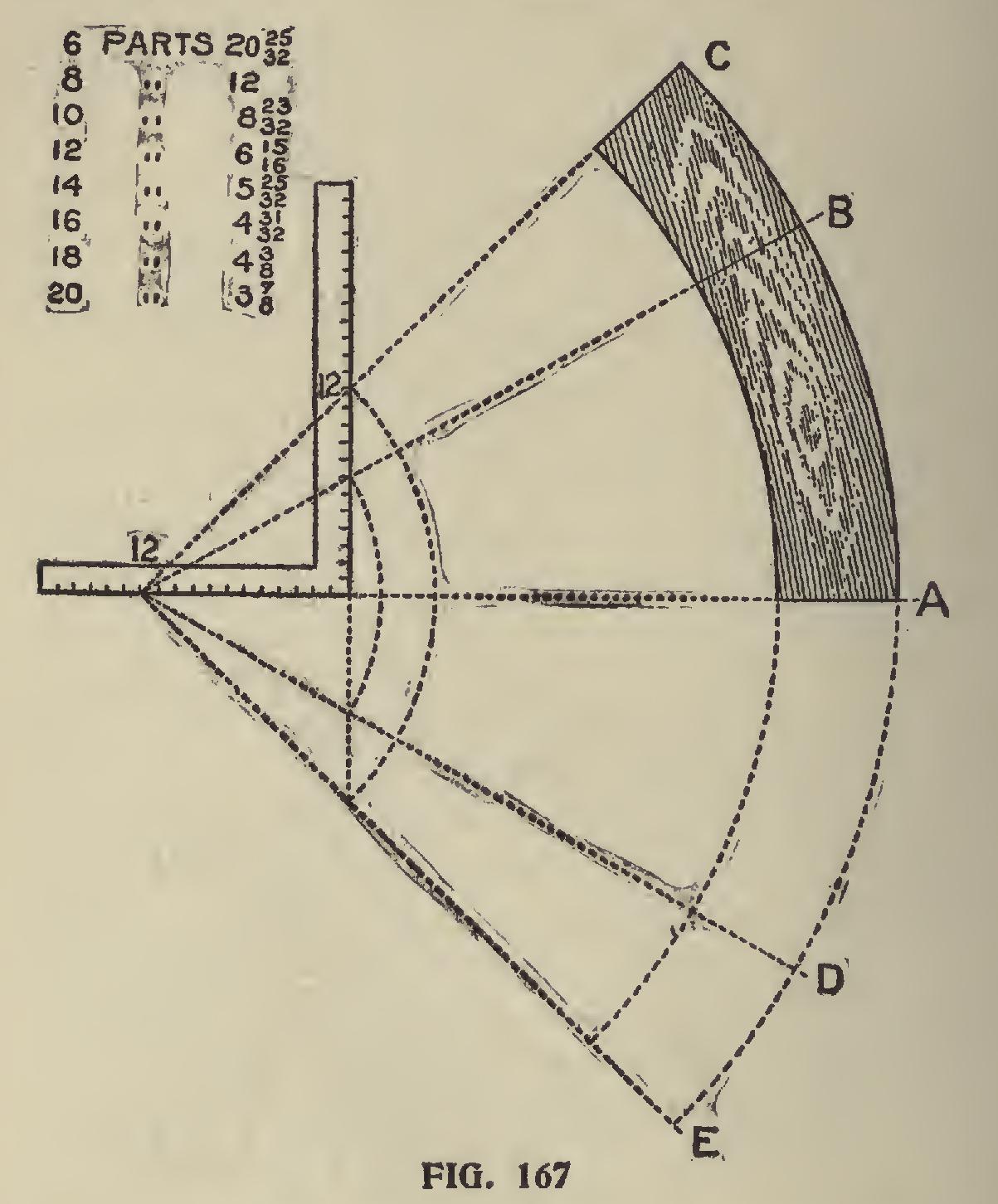

The Sectional Part of a Circular Frame or Wheel can easily be found by the aid of the square as follows: Draw line A, Fig. 167, and on it place the tongue of the square as shown, letting the 12 inch mark be the starting point.

Now suppose we wish to make a frame with eight equal parts. Draw a line from 12 on the tongue, passing at 12 on the blade, and on this lay off the desired radius, and swing down to A. The space from A to C will be the desired part. If twelve parts are wanted then draw the line pas sing at 6 and 15-16 on the blade. The part from A to B being that proportion.

If one-half the parts mentioned above are wanted then these parts may be doubled, or found as shown by the dotted lines below A. Great care must be exercised in laying out the diagram, the least variation of which will be multiplied by the number of parts used.

When making frames of very large diameters, it is better to increase the scale by raising the figures given by doubling, trebling, etc.

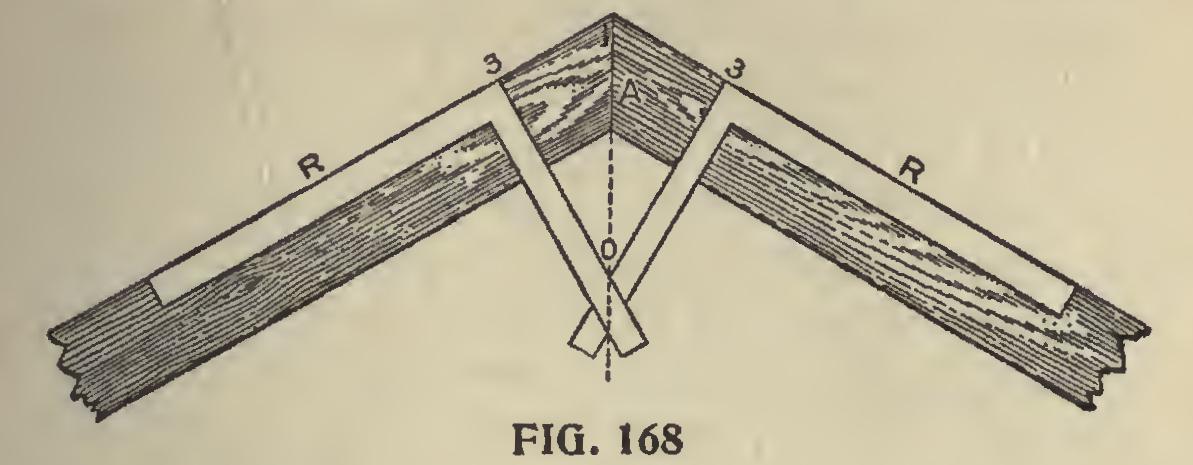

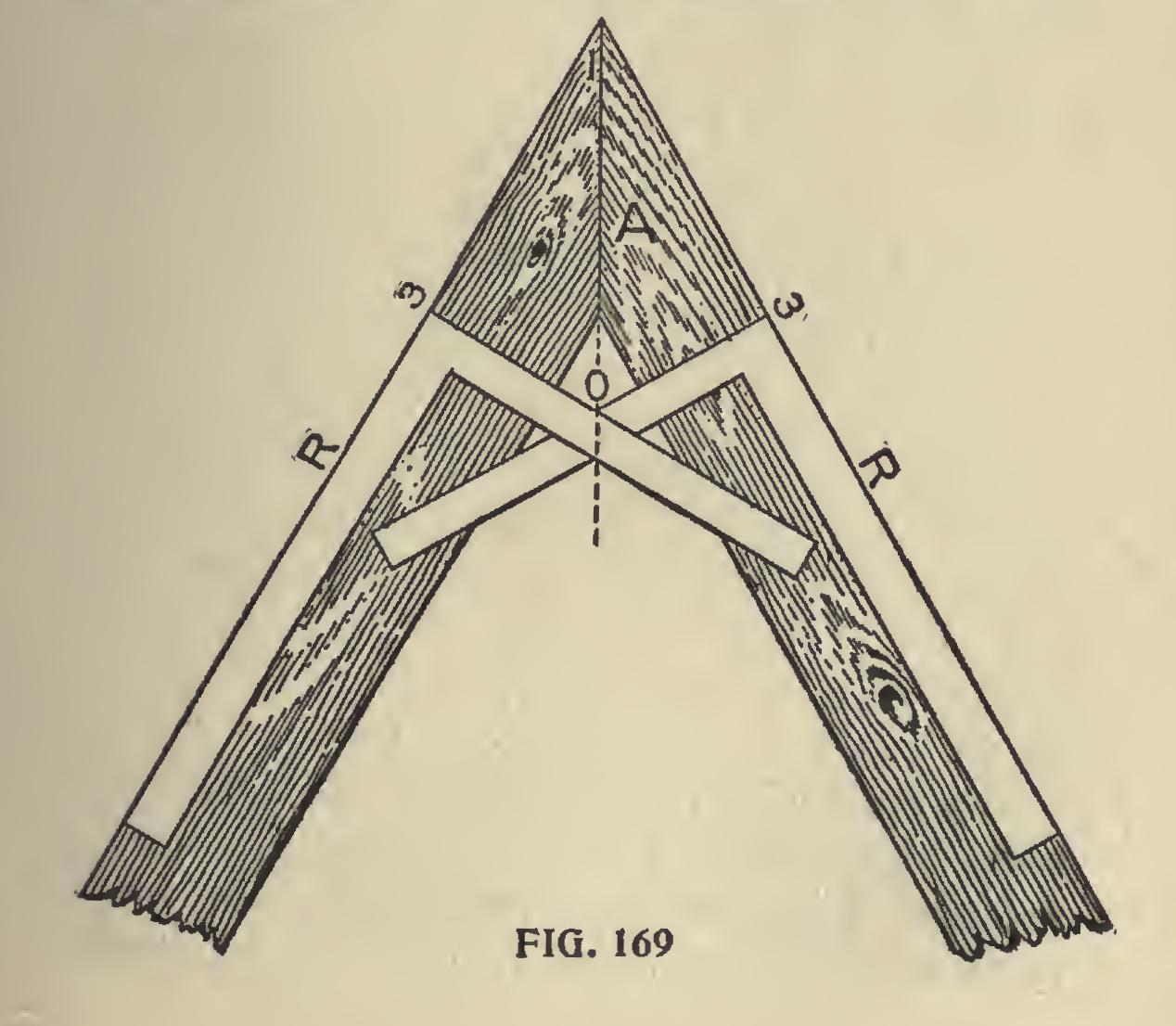

To Lay off a Miter or Equal Joint.

In our experience, we have frequently been asked how a miter, or equal joint, could be laid off by using the square.

The matter is simple, but the many inquiries that have been received induce us to give a few examples of the manner in which advanced work men generally accomplish this end. Let Fig. 168 represent an oblique angle formed by two parallel boards. To obtain the joint A, space off equal distances from the point 1 to 3, 3, then square over from the lines, R, R, keeping the heel of the square at the points 3, 3. At the junction of the lines formed by the tongues of the squares at 0 will be the point to take on the tongue, and 4- on the blade. The latter will give the joint line, A, as defined.

To Find the Line

of Juncture for an Acute Angle, we proceed as follows: Fig. 169 represents two parallel boards; 1 the extreme angle, 3, 3 equal distances from the angle 1 and are the points where the heel of the square must rest to form the lines 0, 3; 0 shows the junction of the lines formed by the tongues of the squares, and then proceed as in the previous example.

It will be seen, by these two examples, that the bevel of a junction at any angle may be obtained by this method.

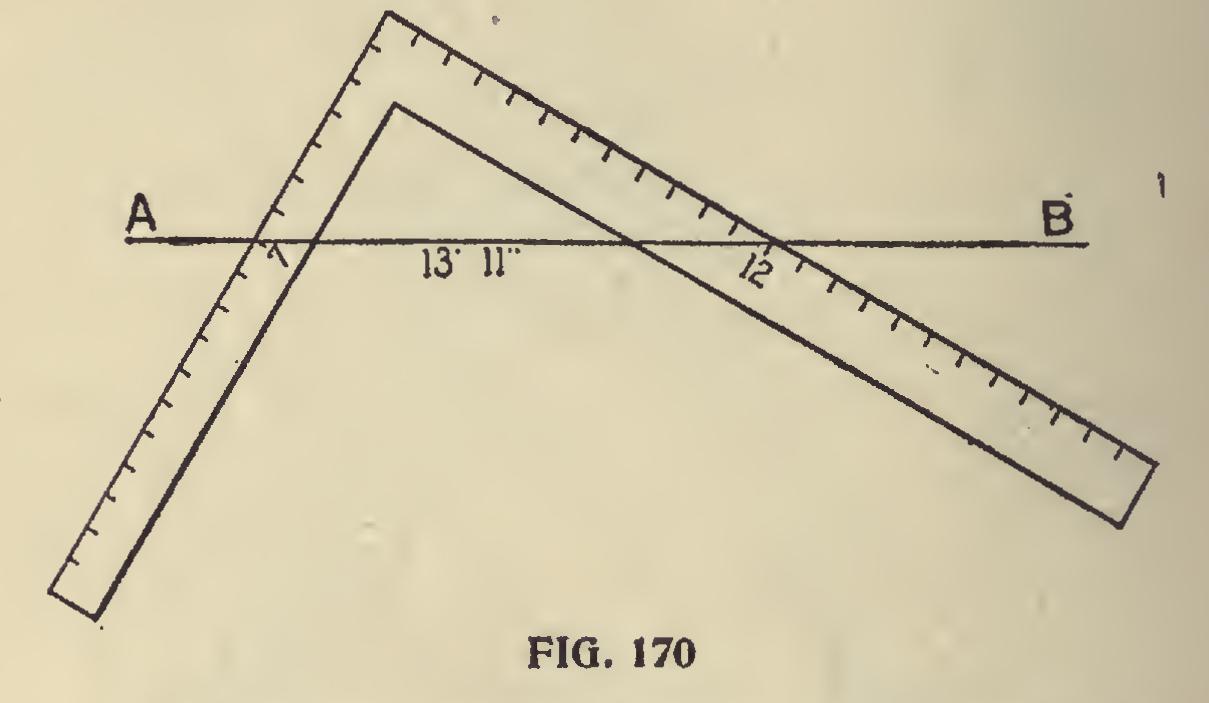

To Find the Length of Braces and Other Tim bers.—Sometimes, when estimating on work, it becomes necessary to get the length of braces and other timbers, that would require considerable fig uring to obtain if the usual method of finding the length of the third side of a right angled triangle were adopted. The square, at this juncture, may be made use of with advantage, where the length of the lines wanted is within the range of the instrument, and almost any dimensions may be manipulated, by making the subdivisions of the inch represent inches, feet or yards. Suppose we want to get the length of a brace with un equal run of 7 and 12 feet respectively. Lay the two-foot rule across the square, putting the end on 7 on the tongue, and cutting the 12-inch line on the blade; then, as shown in Fig. 170, we will have on the side of the rule A B, 13 feet, 11 inches, or say 14 feet, which is near enough for the esti mator's purpose, and if required for working pur poses, the exact length and bevels may be ob tained by careful measurement.