X-Rays and Crystal Structure

axes, symmetry, fig, patterns, pattern, planes, lattice, screw and lattices

X-RAYS AND CRYSTAL STRUCTURE. The idea of a regular, underlying structure has always been at the back of scientific studies of crystals. It is suggested by their very appear ance, and it becomes almost a necessity to explain the regularities of the laws of the arrangements of the external faces, and the physical properties of the crystals. Christiaan Huygens, in the 17th century, first put forward the idea that a crystal was essen tially a regular piling of atoms or molecules similar on a minute scale to a pile of shot or to the blocks of the Great Pyramid. It was not until the beginning of the 19th century, however, that the Abbe Haliy gave it a firm mathematical footing. (See CRYSTALLOG RAPHY.) The idea implicit in Haily's work was that crystals consist of a regular ordering of exactly similar molecules in three dimensions.

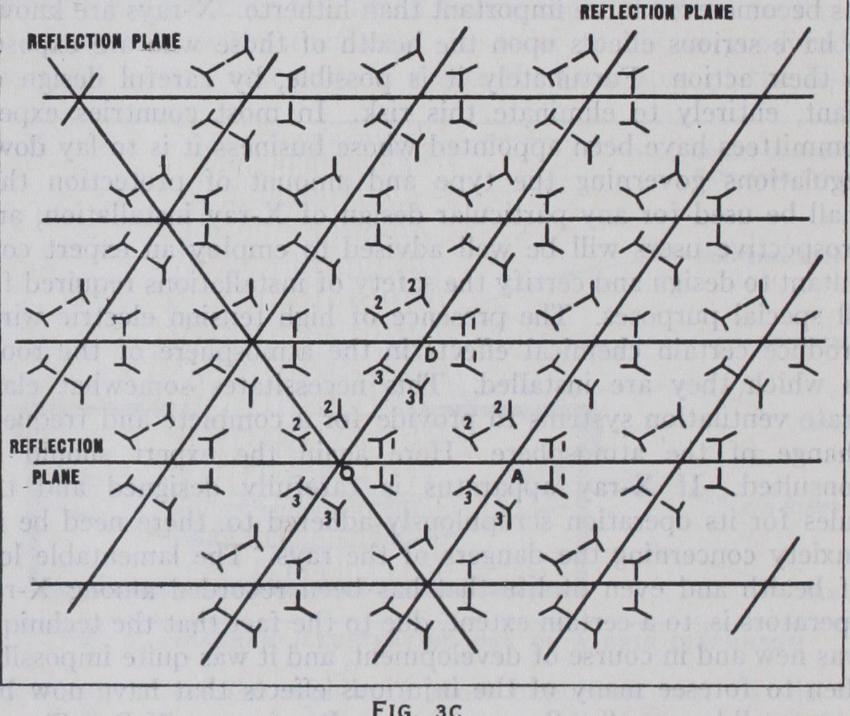

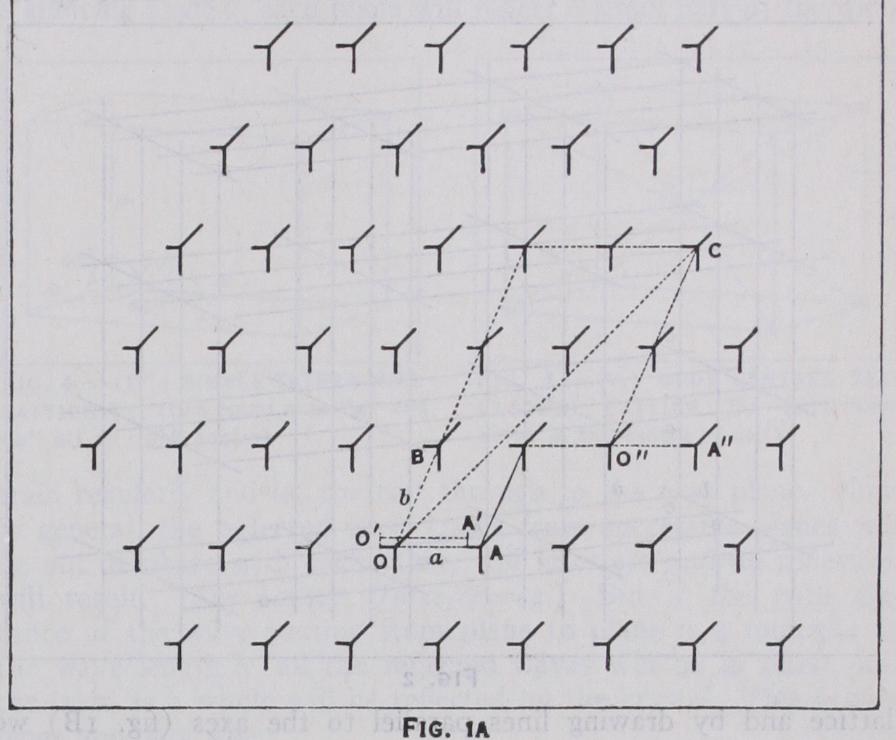

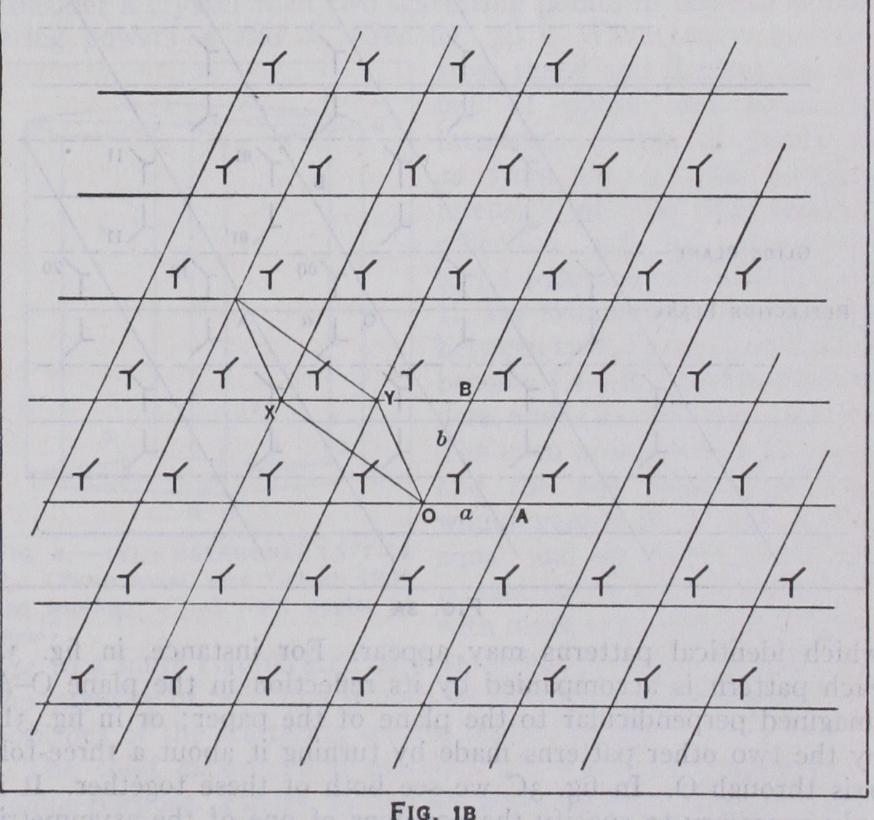

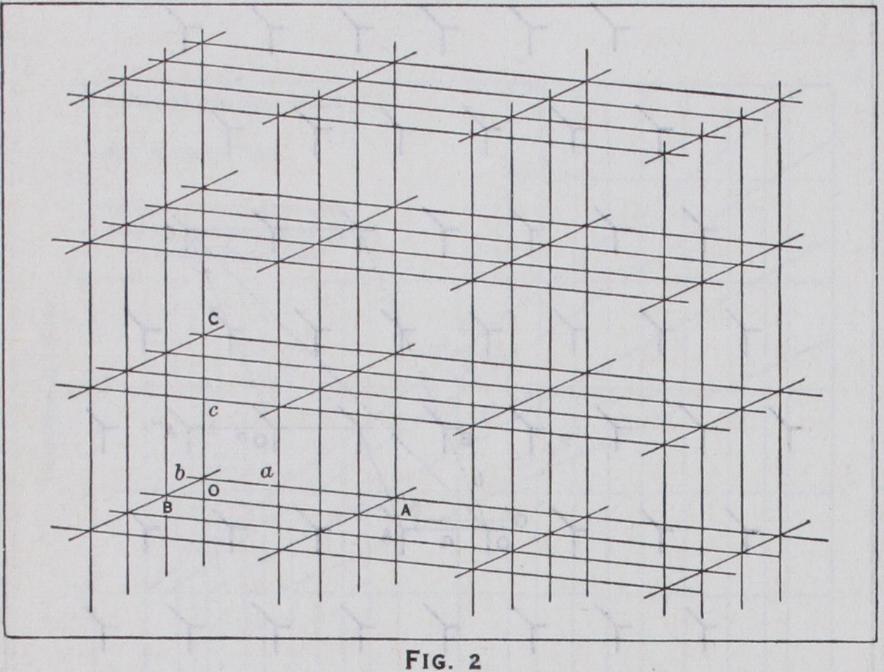

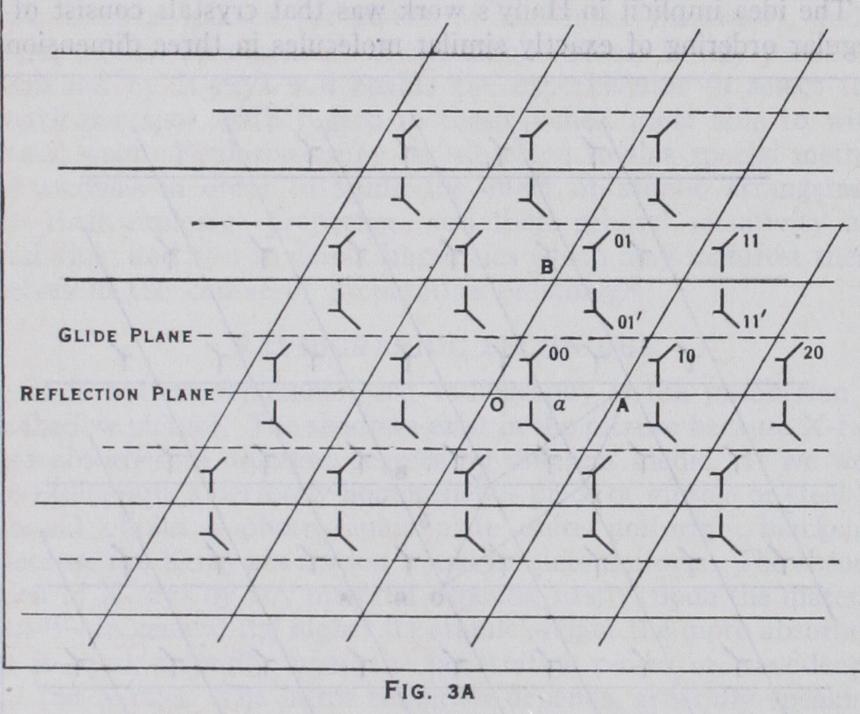

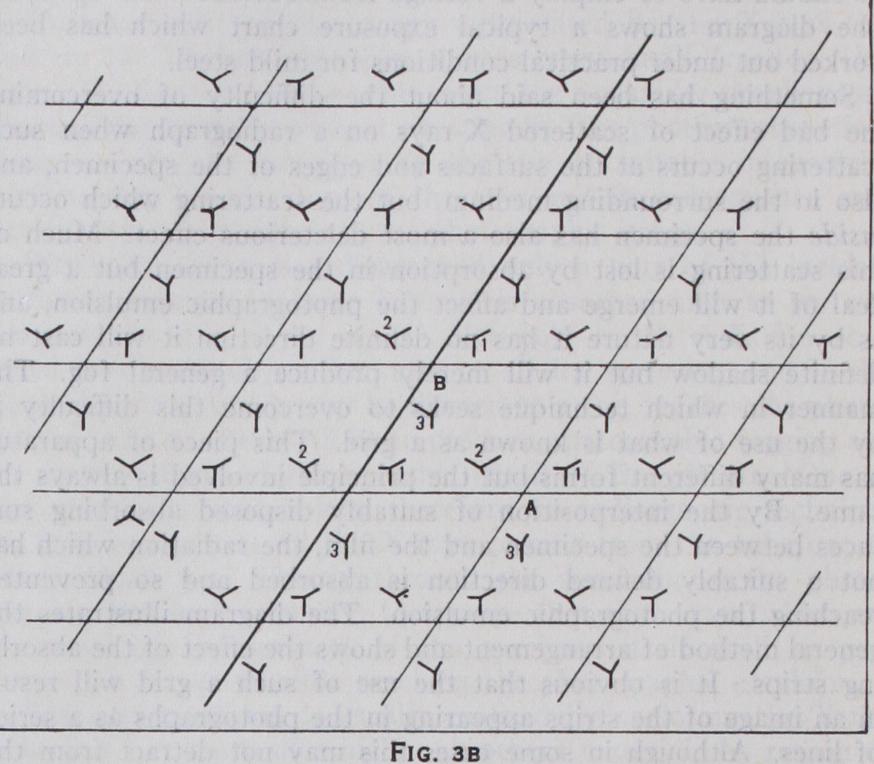

This is easiest to understand from its two dimensional analogue. In fig. IA a set of similarly oriented identical patterns is shown, repeated, supposedly indefinitely. A certain movement 0—A takes me from a point 0 of one pattern to a corresponding point A in another. Now an exactly similar movement O'A' would take me from any point of the pattern to the corresponding point, or from any point in any pattern 0" to a corresponding point on another A". Similarly, the different movement O–B may be seen to have the same property. They are the so-called translations of the crys tal. Now we can easily see that any translation 0–C can be made up of a succession of translations 0–A and 0–B, so that 0–A and O–B may be taken as the primitive translations or the axes a, b of the crystal. All the points derived in this way make up the lattice and by drawing lines parallel to the axes (fig. 1B) we define the cell of the crystal, the contents of all cells being identical. Of course, we might have chosen another set of axes, Ox, OY instead, but the lattice is completely determined in either case by the lengths of the axes and the angle between them, and the whole crystal by the lattice and by the co-ordinates of each point in a single cell, referred to its axes as units. To extend this to three dimensions, we simply have to take another axis c, not in the plane of a–b, and the cells become parallelopipeds, extend ing in space in all directions. (See fig. 2.) Symmetry.—Now there are other ways than translations in which identical patterns may appear. For instance, in fig. 3A each pattern is accompanied by its reflection in the plane 0–A, imagined perpendicular to the plane of the paper ; or in fig. 3B, by the two other patterns made by turning it about a three-fold axis through 0. In fig. 3C we see both of these together. It is only necessary to specify the positions of one of the asymmetric patterns in the cell, and the nature of the symmetry, to define the crystal as completely as before. The elements of symmetry per

mitted in space lattices are essentially those of crystallography, that is, two, three, four and six-fold axes, centres of symmetry, , reflection planes and axes of the second sort. (See CRYSTALLOG RAPHY.) But there is the important condition that all axes must be translations and all planes lattice planes, and in addition, there are glide planes and screw axes. In fig. 3A we have the two rows of patterns (marked ), each of which can be seen to be a reflection of the other in a plane, but which has also been moved on a half translation of the cell. This is called a glide plane re flection. An ordinary axis of symmetry is a pure rotation, but screw axes move the pattern a fraction (4, +, or *) of the lattice translation, parallel to the axis in each operation, so that at the end of a complete turn the pattern has moved through one trans lation, e.g., three-fold screw axes perpendicular to the paper are shown in fig. 19. Screw axes may be right or left handed. In nature they are familiar as phyllotaxy, the arrangement of leaves on a stem.

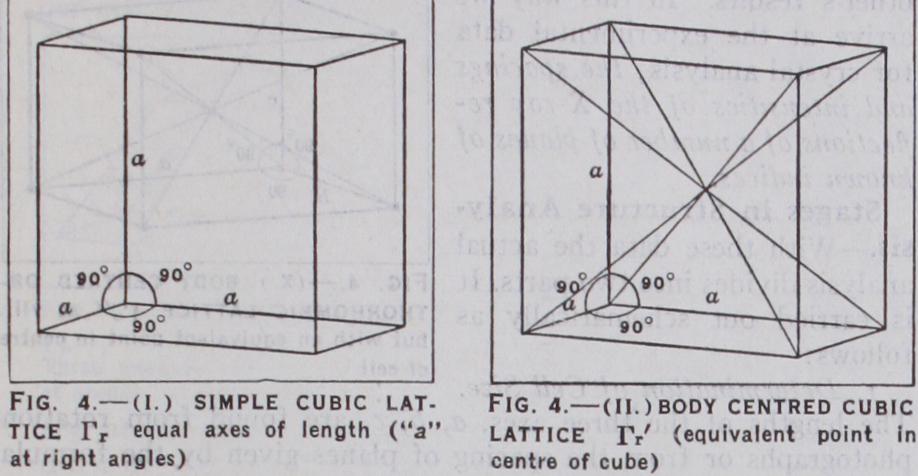

The considerations of symmetry give us an ultimate method of classifying any regular arrangement of patterns in space. First we can divide the lattices into the fourteen types of Bravais (1811-1863). (See fig. 4.) The seven systems of symmetry, cubic, tetragonal, hexagonal, rhombohedral, orthorhombic, monoclinic and triclinic, give rise to the simple lattices (i.) (iv.) (vi.) Ph, (vii.) rrh, (viii.) (xii.) (xiv.) But be sides these there exist a number of face centred lattices [where the primitive translation is not from corner to corner of a rectangular face but to its midpoint]; one face centred (ix.) (xiii.) or all face centred (iii.) (xi.) rom. Lastly, there are the three body centred lattices [where the primitive translation is to the centre of a rectangular parallelopiped rather than to its opposite corner]; (ii.) r,', (v.) (x.) Next, we can divide the symmetry further, according to the nature of the axes and planes and the presence or absence of centres of symmetry into the thirty-two crystal classes. (See CRYSTALLOGRAPHY.) But the existence of glide planes and screw axes permits of still further divisions inside each class, and for each variety of lattice possible in that class. If these two are specified, the complete inner symmetry or space group of the crystal is given. The determination of the two hundred and thirty possible space groups was begun by Sonchke and finished by Schoenflies, Fedorow and Barlow at the beginning of the present century.