X-Rays and Crystal Structure

ions, fig, atoms, crystals, adamantine, simple, compounds and molecules

When lies between .41 and •2 2, the co-ordination number is 4:2, which is approaching an adamantine structure. This is the case for the different forms of silica, Cristobalite, Tridymite and Quartz. These are shown in figs. 17, 18 and 19. Though ap parently different, these structures have the essential point in common that they are built from silicon ions completely sur rounded by four oxygens in a tetrahedron. Each oxygen is shared between two tetrahedra and the different forms of structure are merely due to different arrangements of these tetrahedra. Thus the polymorphism of silica is not due to any change in the mole ' cule.

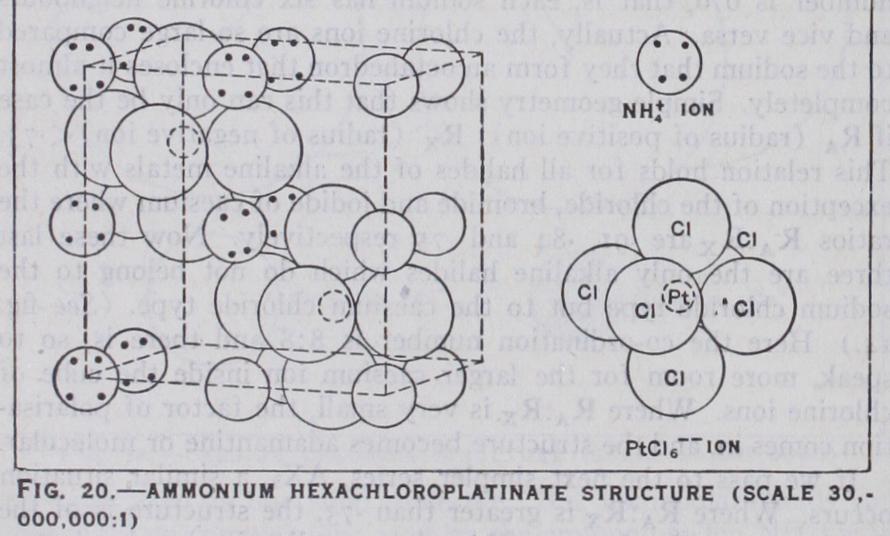

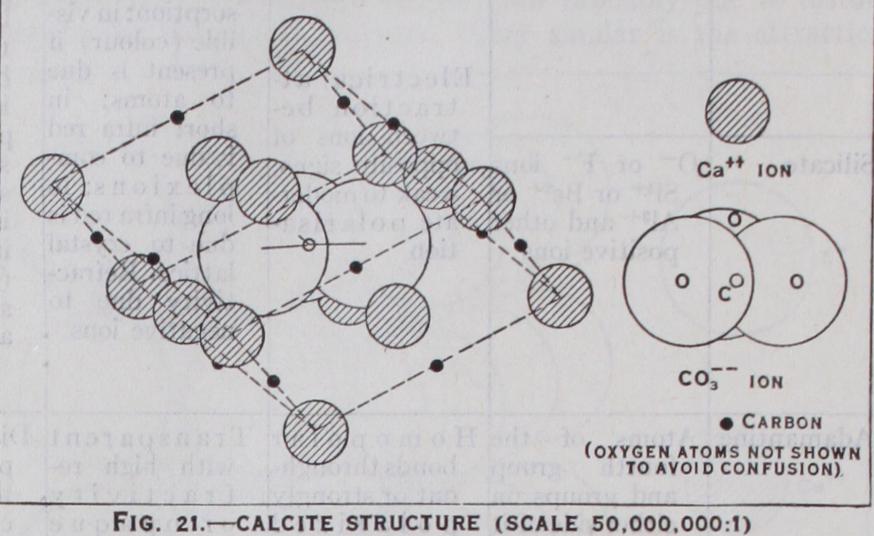

So far we have dealt only with crystals with simple ions, but those with complex ions are essentially similar. When the ion is approximately spherical, as is ammonium or highly sym metrical as can take its place in a crystal exactly like a simple ion of the same 'size. Ammonium, is practically indistinguishable in its compounds from Rb+. Such 9 • • ' a compound as (PtC16) (see fig. 20) is, except for its larger size, essentially the same as fluorite. When the compound ion is not nearly spherical, loss of symmetry results. In the case of calcite (see fig. 21), for instance, the ions are arranged very much as in rock salt, but owing to the flatness of the ion, one trigonal axis is shortened, leading to a rhombohedral crys tal. A number of crystals, such as and belong to the calcite class. With ions of the type such as BF4, C104, structures are of even lower symmetry, though in all of these the tetrahedral arrangement of oxygen atoms is maintained.

Silicates.

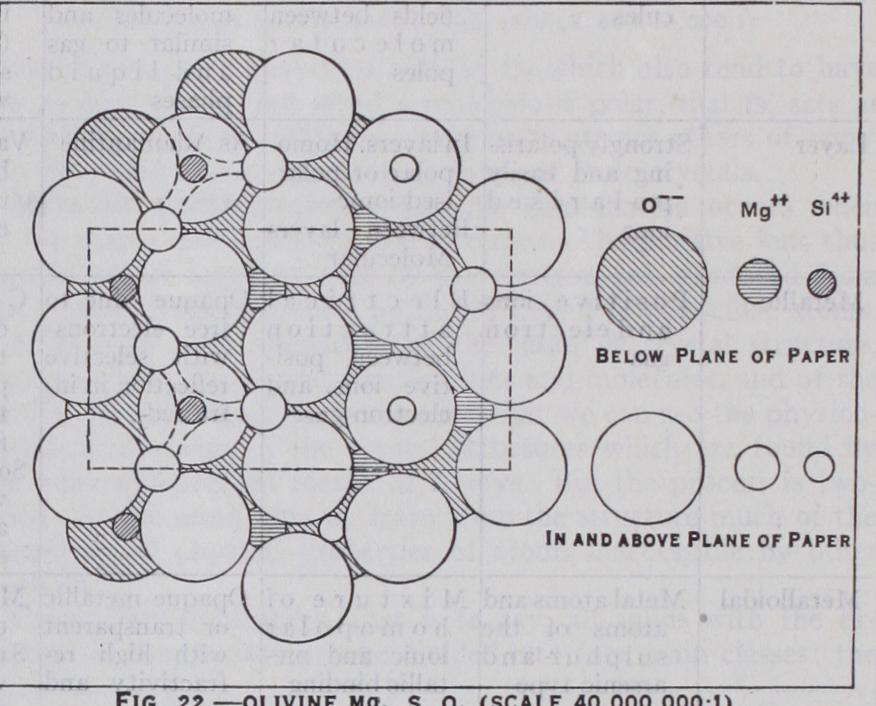

There are a great number of ionic crystals which are neither of the simple ionic or complex ionic types, which may be grouped together as a silicate type, though not all con tain silicon. The structure of the silicates are complex but, as W. L. Bragg has shown, they consist essentially of oxygen ions in a close-packed arrangement, either cubic or hexagonal (See figs.

31

and 33.) These ions are held together by strongly charged me tallic ions, which occupy the spaces between them. In the tetra hedral spaces are found the smallest and most highly charged ions Be ++. In the octahedral spaces larger ions with smaller charges, such as Mg++. Fe++. Still larger ions, such as Na+ or K+, introduce distortions into the structure. The symmetry of the silicates adjusts itself to fit these ions with th( minimum distortion, which leads to large and complicated cells generally of low symmetry. One of the simplest of these olivin( Mg2SiO4 is shown in fig. 22. Other silicates of known structure inelude cyanite Al2SiOs, phenacite beryl anc the garnets Two non-silicate types are also built from close-packed oxygens, the corundum type including haematite Fe203 and and the spinel type Al2Mg04, includ ing magnetite Fe2Fe04 and Ag2M004.

Adamantine Crystals.

In adamantine crystals the forces binding the whole crystal together are homopolar, so it may be considered that they are single molecules. The typical adamantine crystal is the diamond. (See fig. 23.) Here each carbon is joined to four others (co-ordination 4 :4) by a homopolar electron shar ing bond in a tetrahedral fashion, alternate tetrahedra pointing in opposite directions. If we replace alternate carbon atoms with zinc and sulphur, we arrive at the zinc blende structure, which is typical for adamantine compounds. Such compounds are chiefly found in the fourth group of the periodic table and in compounds between elements of the neighbouring groups on either side. For instance, we have Compound GaGe GaAs ZnSe CuBr Atomic Numbers 32 32 31 33 30 34 29 35 Interatomic dist. 2'435 2'45 2.46 A all with diamond structure. It should be noticed that here, un like the case of KC1 and CaS, there is little change in interatomic distance. Another 4:4 is represented by Wurtzite (see fig. 24), the other form of zinc sulphite. The relations and the distances of neighbouring atoms are the same in both cases, but in Wurtzite, the symmetry is hexagonal instead of cubic. The three forms of carborundum represent a compound diamond-Wurtzite structure.