X-Rays and Crystal Structure

atoms, parameters, atom, intensity, cell, analysis, atomic, structures and intensities

Once the space group is known and the number of molecules per cell, the symmetry of the individual molecule follows, which is in general lower than that of the crystal. Further, the condi tions of symmetry fix the posi tions of the atoms within cer tain limits. If we designate the co-ordinates of the atom, referred to the axes a b c as u v w, the so called parameters of the atom, then the symmetry conditions may fix the values of u v w within certain limits. If there are very few atoms of a particular kind in the cell, u v w may become 0 0 0 or 1/2 1/2 1/a, that is, the atom must be at a corner or in the centre of a cell. Or two parameters may be fixed, o o v, fix ing the atom anywhere on the c axis; or o v w, fixing it anywhere in the a plane. However, it is only in the simplest cases that the symmetry positions fix all the atomic positions. Usually, a set of independent parameters are left undetermined, which may be only one, as in graphite, or twenty or more as in a silicate. The difficulty of fixing parameters leads to many crystals being left at this stage, but though it is indirect, the fixing of parameters by means of intensity considerations is far the most interesting part of crystal analysis.

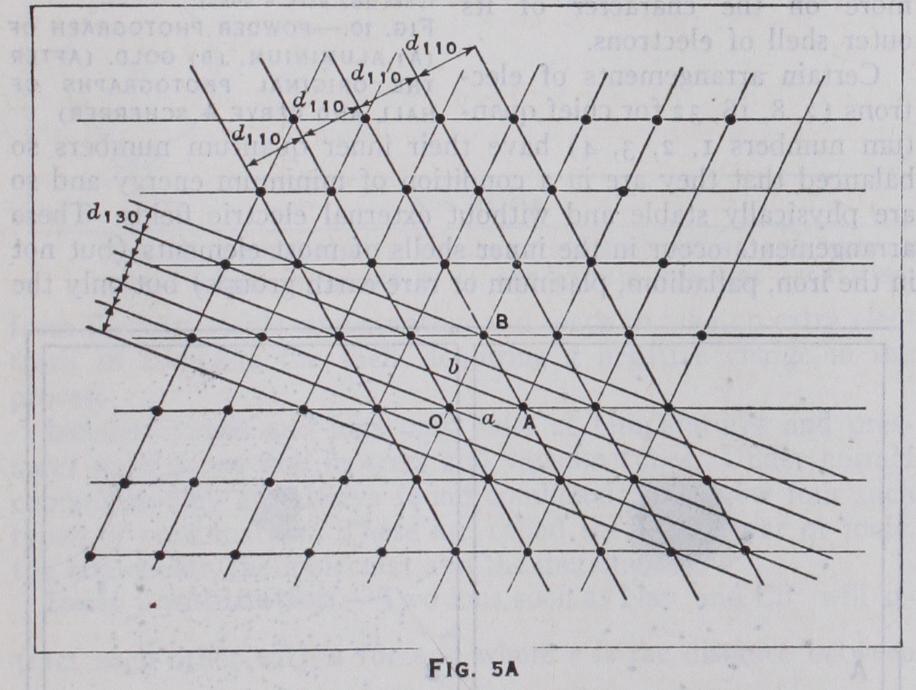

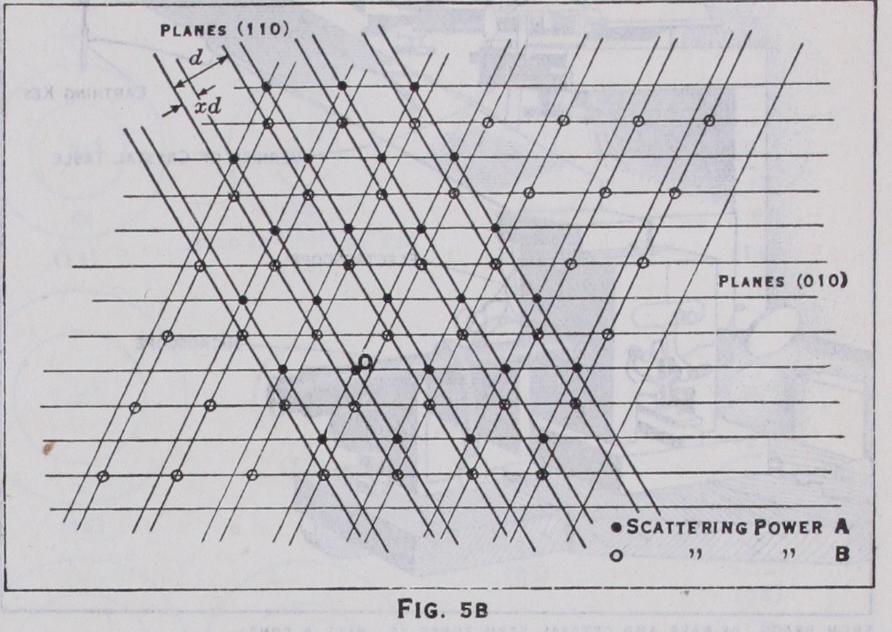

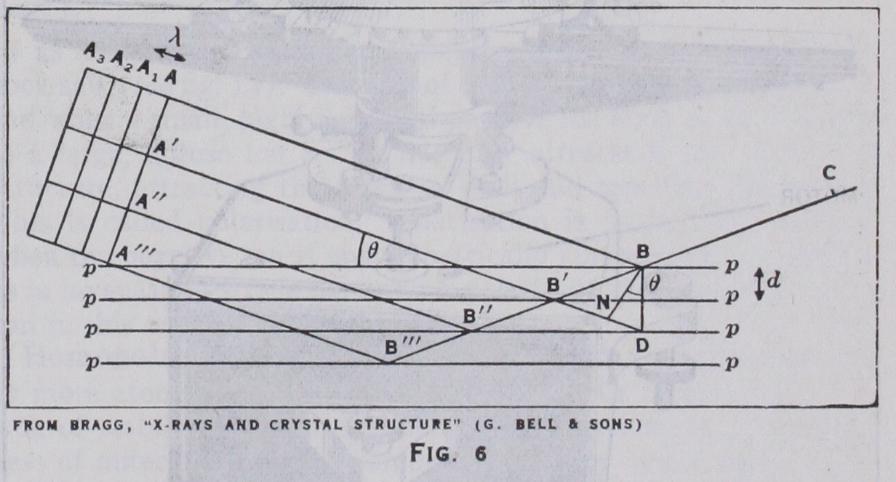

The method consists in assuming certain values for the para meters and calculating from these the theoretical intensity of re flections from a set of planes. These are compared with the ob served intensities, and the process repeated by trial and error, until the theoretical and observed intensities agree within the errors of the experiment. In many ways this method resembles the solution of a cross-word puzzle. The cell and space group provide the square and the pattern, the atoms the letters and the intensities the Atomic Structure Factors.—The amplitude of the reflection from the plane (hkl) of a crystal which has n atoms per cell with the parameters //I vl ZFI1, u2 v2 w2, v„ w. is given by C o is the J. J. Thomson formula for the scattering from a single electron, which depends only on the angle of scattering 0. F1, F2, . . . F. are the so-called structure factors of the different atoms. If the atoms scattered as points, the total number of electrons in the atom. Actually, the electrons are diffused in space, so that their scattered radiations interfere, making F fall off very rapidly with the angle 0, particularly for light atoms. Structure factor curves giving can be found experimentally for each kind of atom or calculated from the wave mechanics distribu tion of electricity in the atom, as has been done by Pauling and Hartree. The exponential terms simply allow for the phase difter ence of the different atomic centres for the reflection of the plane (hkl). The observed intensity, before comparison with the calcu lated, must itself be corrected for absorption of the X-rays in the crystal, which is complicated by the fact that the very reflections of the X-rays increase the absorption differently for each plane.

Corrections must also - be made for temperature effects, as the atoms in a crystal vibrate more at higher temperatures, which reduces the reflection The calculation and comparison of intensities is a lengthy but straight-forward process, but the assigning of parameters is like solving a geometrical problem and always depends, in part, on intuition. Gradually, however, as more and more structures are being worked out, probable arrangements of atoms can be seen more easily, particularly by the use of the ideas of atomic diame ters and co-ordination numbers (see Part II.). It was by the use of these that Pauling and West successfully and independently predicted the structure of topaz Al2SiO4F2. But however the parameters are obtained, good intensity agreement absolutely confirms the structure as correct because the slightest change of atomic position causes such changes in intensity distribution be tween the different reflections as to wholly upset the agreement.

This completes our account of the methods of crystal analysis as far as the positions of the atoms are concerned. Unfortunately, to illustrate it with even a single example, would exceed the length of this article, and the reader must be content with the results of the analysis given in Part II. Strictly, however, merely to know the position of the centres of the atoms in a crystal, is only the beginning of a real knowledge of their structure. A complete knowledge must also include a quantitative account of the forces by which the crystal is held in equilibrium and of the dynamics of the crystal when it is acted on by mechanical or electrical fields. Such an account should give all the mechanical and physical properties of the crystal in terms of its structure. This part of crystal analysis is only beginning, but already the work of Born, Lande, Leonard Jones, Joffe and several others has accounted quantitatively for the mechanical properties of simple ionic crystals, particularly of the rock salt type.