X-Rays and Crystal Structure

crystals, fig, atoms, metals, structures, ionic and compounds

If a molecule possesses unbalanced electrical poles, these arrange themselves in the crystal so as to neutralize each other as much as possible, either by polymerising or forming pseudionic crystals; thus ice formed from the strongly polar has tridymite structure (see fig. 18), in which each oxygen is sur rounded by four hydrogens, or calomel C1HgHgC1 (see fig. 27), in which the mercury atoms are surrounded by chlorines.

Layer Crystals.

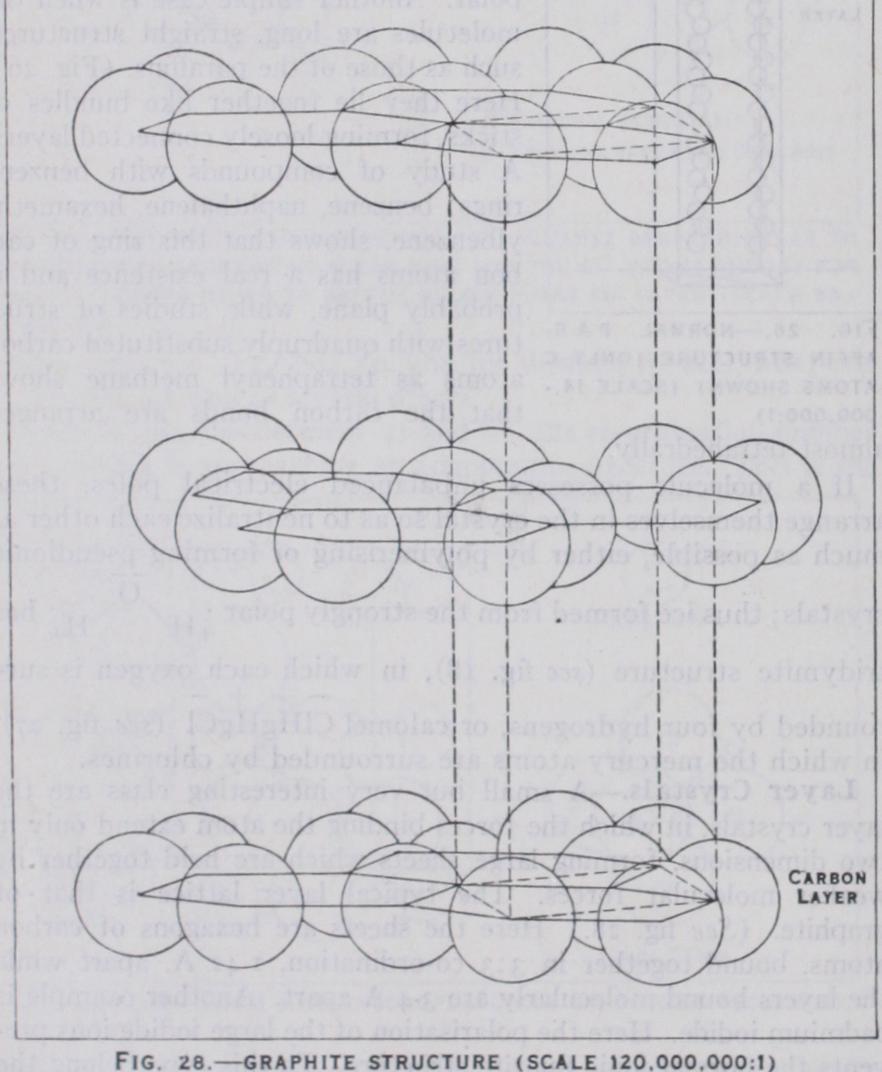

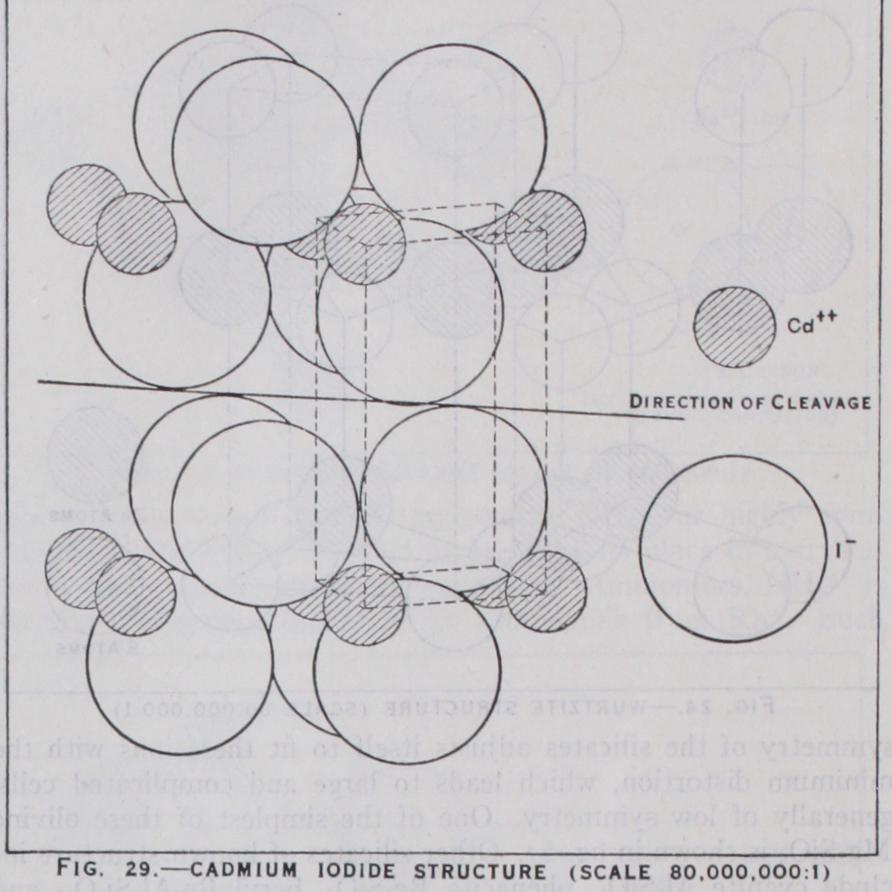

A small but very interesting class are the layer crystals, in which the forces binding the atom extend only in two dimensions, forming large sheets which are held together by weaker molecular forces. The typical layer lattice is that of graphite. (See fig. 28.) Here the sheets are hexagons of carbon atoms, bound together in 3:3 co-ordination, 1.42 A, apart while the layers bound molecularly are 3.4 A apart. Another example is cadmium iodide. Here the polarisation of the large iodide ions pre vents the normal ionic fluorite structure. To this type belong the hydroxides Ca(OH)2Mg(OH)2 and the sulphides ZrS2, SnS2.

Metals.

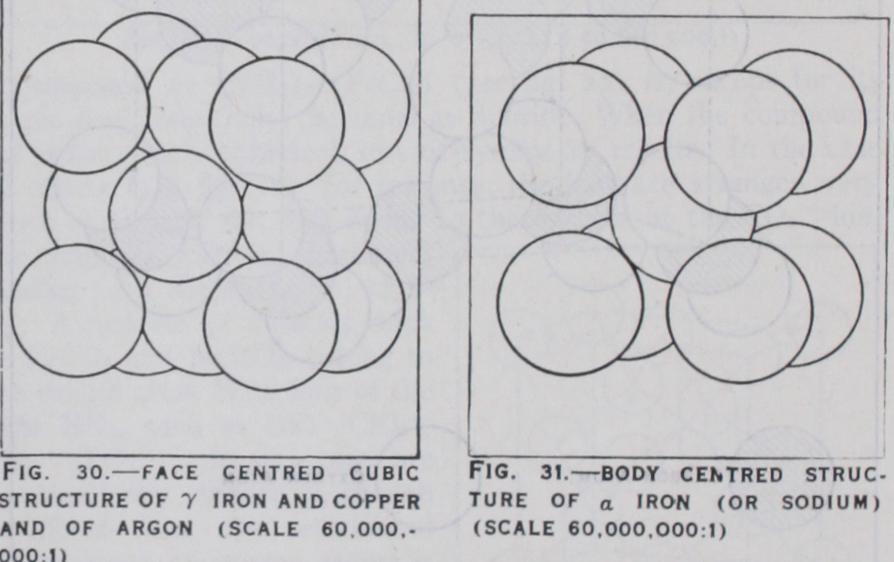

Metallic crystals differ from the previous classes by the presence of free electrons, the attraction between which and the positive ions gives the structure its stability. The basis of the structure of pure metals and alloys is one of close packing, but the radii of atoms in metals are much greater than those of the corre sponding ions in ionic crystals. (See fig. 12.) The pure metals have very simple structures: face centred cubic for Cu, Al, Fe,(see fig. 30 ); body centred cubic for Na, Feu, Feb (see fig. 31) and close packed hexagonal cubic for Mg, Zn, W (see fig. 32). Several metals have phases with different structure. Iron, for instance, between the temperatures i ioo° and 1425°, has a face centred cubic structure. Both above and below this temperature, its structure is body centred. Manganese has two forms with very complicated cubic structures, and tin, at low temperatures (grey tin) is like diamond, while at ordinary tem peratures (white tin) it has a distorted diamond structure.

Our knowledge of the real con stitution of alloys is immensely furthered by X-rays. They are essentially of two types, solid solutions and compounds. In

solid solutions, the atoms of one metal are replaced by another, distributed by chance throughout its structure. This is shown by an X-ray pattern similar to the pure metal but with a different size of cell. In inter-metallic compounds on the other hand, the atoms of the different metals have defi nite positions similar to those in ionic compounds, such as CuZn, which is like CsC1 but usually more complicated, with a tend ency to large cells of high symmetry. 5 Bronze Cu31Sn8, for in stance, has a cell of side 17.9 A. and 416 atoms. The laws of cornbination in metallic compounds are quite different from those of ordinary chemistry, but seem to depend on electron numbers. Metalloidal Crystals.—There are a number of substances which show resemblances to both metallic, adamantine and ionic crystals. They may be roughly classed together as metalloidal These include the semi-mctals Se, Te, As, Sb, Bi and a great number of simple and complex arsenides, antimonides, sulphides, selenides, etc. They resemble the metals in having free or loosely bound electrons, which makes them in a lesser degree opaque and conducting, and also by the complexity and indefinite composition of many compounds such as the fahlerz group. which contain Cu, Ag, Hg, Pb, Fe, As, Sb--S, in varying proportions. The struc tures, however, are much less close-packed and resemble adaman tine structures. Some, however, are more like ionic structures. Typical are pyrites (see fig. 33), which is a rock salt structure with Fe++ in the place of Na+ and the complex ion in that of Cl'. Another is the nickel arsenide structure, hexagonal with 6:6 co-ordination, to which many substances belong.

Technical Applications.

This completes the systematic ac count of the structures of crystals. but X-rays have proved use ful, not only in determining the positions of atoms in crystals, but of the arrangement of minute crystals in materials. It is possible by means of X-rays to find the position of the crystal axes of crystals far too small to be seen microscopically and to study their arrangement in relation to the properties of the ma terial. This has been done in textiles, ceramics and metals.