X-Rays and Crystal Structure

wave, plane, planes, reflection, reflected, waves, crystals, intensity and nature

Laue's Discovery.

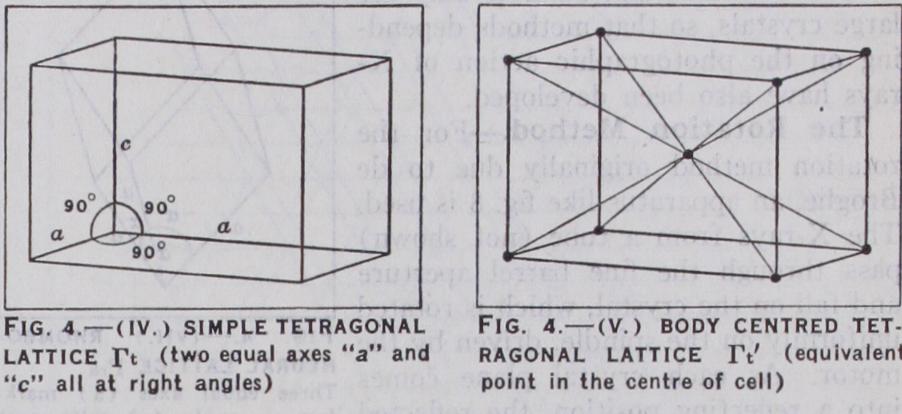

But though the geometrical frame-work for the complete description of crystal structure had thus been worked out, there remained no way of applying it, for it was im possible to determine either the nature of the lattice, the existence of screw axes and glide planes or even the size of the cell, much less the positions of the atoms in it. Yet the labour of the mathe maticians was not wasted. Soon after they were concluded, there was a controversy as to the nature of X-rays. Some maintained they were corpuscular and others that they were waves analogous to light. However, no one had then succeeded in diffracting them with a grating. (See LIGHT.) This seemed to show that if they were waves, their wave lengths must be much less than that of visible light, cm. Now early in 1912 it occurred to von Laue, then a young physicist at Munich, who was in touch with the Crystallographic School of Groth, that the lattices of crystals, of which the little that was known indicated a periodicity of cm., were of the right order to act as a grating for X-rays, and, if they were waves, to diffract them in definite directions. Friedrich and Knipping carried out the experiment of passing a narrow beam of X-rays through a crystal with a photographic plate behind it.

The experiment was strikingly successful. The plate was cov ered with a regular pattern of spots, which was what von Laue had predicted. This experiment gave the key both to the nature of X-rays and the structure of crystals.

The Braggs' First Crystal Analyses.—The new discovery aroused immediate interest. In England it was taken up by Sir William Bragg and his son, W. L. Bragg, who in the same year determined the first crystal structures, those of rock salt and zinc-blende; and at the same time developed a method of analysis which was to be the basis of all further work. The way in which they accomplished the double task of determining the wave lengths of X-rays and the structure of crystals is told in their classic book, "X-rays and Crystal Here we will simplify it by assuming from the start that we can produce X-rays of single wave length X (most easily from the fluorescent radiation of metals such as iron, copper and rhodium. See X-RAYS, NATURE OF).

Bragg's Law.—The action of X-rays on crystals is best dealt with as selective reflection from crystal planes. If a set of planes be drawn through corresponding points in a crystal (see fig. 5A), not necessarily in any relation to the superficial faces, these will be a constant interval apart. This is the spacing of the plane dhkl ; ( [hkl] are the Millerian indices, that is, the reciprocals of the fractional intercepts on the axes. See CRYSTALLOGRAPHY). If a train of waves falls on such a set of planes p (see fig. 6) at a glancing angle 0, each plane will reflect a small part of the wave train regularly and let the rest through to the next plane. Now, in general, the reflected wave trains from successive planes will be out of phase with each other, will interfere and no reflection will result. (See LIGHT: Interference.) But if the path dis

tance of the wave passing from plane to plane is a multiple of the wave length X, all the reflected waves will be in phase and the train as a whole will be reflected by the crystal. This occurs when and only when sin0=nX/2d.

This is the fundamental relation of crystal analysis known as The integer n is the so-called order of the reflection. Thus the same plane will reflect at angles e1, 02 . . . On, where sine, = sin02= 2X • . . for the same wave 2d 2(.1 length. The higher the order or the smaller the spacing, the larger the angle of reflection. No plane whose spacing is less than half the wave length reflects at all. It is only necessary to measure 0, the angle at which X-rays of known wave lengths are reflected by a crystal, to know the spacing of its lattice planes.

But X-rays are able to give much more information than this.

Consider a crystal with two scattering points in the cell of scat tering powers A and B. (See fig. 5B.) Wave trains scattered 1 from the A and B plane are now out of phase and necessarily interfere. If the B planes are xd from the A's, the resulting intensity of the nth order of reflection will be proportional to (A If, for instance, B was half way between two x=1, this would become for the even or ders and (A for the odd. The even orders would be strong and the odd weak, and these would vanish if A and B were equal, and the plane in this case is said to be halved. A crystal with more scattering points gives rise to a more complicated expression but it should be clear that the intensity of reflection is both an indication and a check on the positions of the scattering centres inside the cell.

The chief experimental methods are therefore devised for a double purpose. Firstly, to find the glancing angles for the X-rays reflected by the different planes of the crystal, and secondly, to measure the intensity of the X-rays reflected. There are four chief experimental methods.

In the Bragg ionisation spectrometer (see fig. 7) the X-rays from the tube inside the lead box pass through the two slits which limit them to a narrow beam, and meet the crystal mounted to rotate about a vertical axis. The reflection beam is received in an ionisation chamber, in which there is an absorb ing gas such as methylene iodide, producing ions which charge the electroscope. The crystal and chamber are moved to record each reflection. Their angular position gives the glancing angle, while the ionisation current is a measure of the intensity. The Bragg spectrometer undoubtedly pro vides the most thorough method, but it is slow in action and suitable only for large crystals, so that methods depend ing on the photographic action of X rays have also been developed.