Elements of House Framing

floor, joists, sills, finish, joist, shown, laid and method

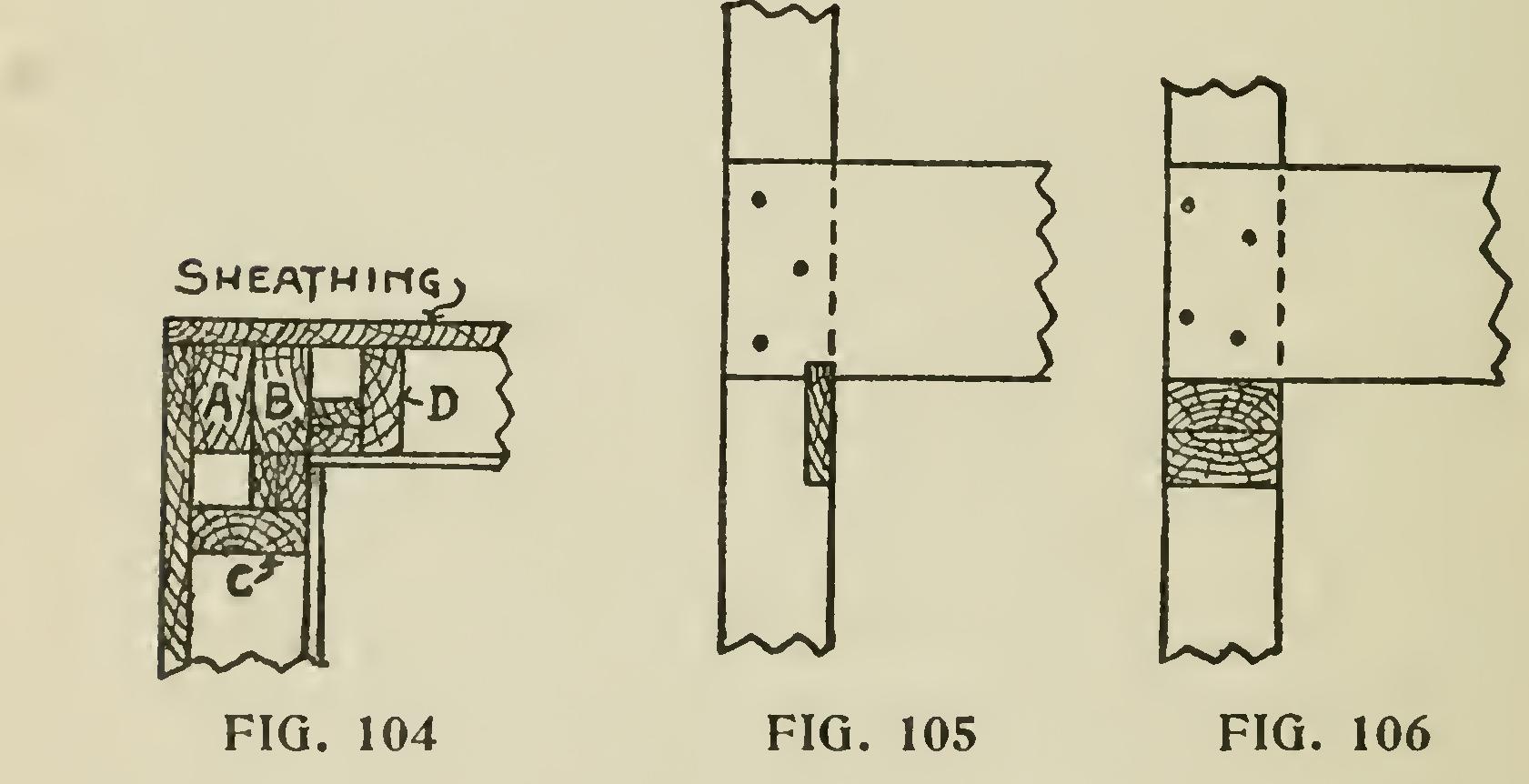

Framing Sills.—Ref erring to the sketches, Fig. 102 represents a method of framing sills for light framing without gaining the joists into the sills. This method consists of using a 2 by 4 or 2 by 6 flat on the wall, and spiking a 2 by 8 or 2 by 10 on the face edge, as shown by A and B. This will allow the floor joists to be spiked through into the ends of the frame, as shown. The floor joists are to be gained on the bottom to have a good bearing on the piece A, and should be cut to fit tight against the face piece B. After these two pieces are thoroughly spiked together, then put on the third piece C and thoroughly spike the same. Allowances should be made in cutting the timbers so that they will work out right and bring the finish out flush with the wall, or as in tended if otherwise shown. In most cases where houses are sheathed with seven-eighths sheathing it is best to keep the frame back one inch from the wall, so that when the sheathing is put on it will come flush with the wall, then there is noth ing to project over the wall at the bottom but the outside base, as shown.

This method of framing makes a very strong frame, and if well spiked it is fully as strong as solid timbers of the same dimensions. Two 2 by 8's and one 2 by 4 are just a little more than equal in cross section to a 6 by 6, and it is safe to say that they are stronger than a 6 by 6 gained out to receive the joist. The built-up sill has much the advantage in making splices. In splic ing, the joint can be so broken that when put together it will be like one continuous sill all around the building. The cut shows the sheath ing, outside base, water table, siding and a double floor. Where double floors are laid the first rough floor should be laid diagonal, or stripped, before laying the finish floor. Where both floors are laid the same way the shrink of the lower, or rough floor, is often enough to cause great cracks to appear in the finish floor. This is due to the fact that the rough floor boards are usually 12 inches wide, and the finish flooring boards only about three inches wide, thus each twelve-inch board will take four of the three-inch boards, and the joint in the finish floor that comes nearly over the joint in the twelve-inch board below will draw apart very often clear out of the matching, conse quently the rough floor and the finish floor should never be laid parallel, unless the rough or first floor is first stripped over the joists and the finish floor laid on top of the strips. When this is done both floors may be laid the same way without any danger of the shrinking cracks as stated above. To lay the rough floor diagonal gives a

much stronger job and, as a rule, a more even floor for the finish floor.

Method of Halving 103 shows the usual method of halving sills together at corners in framing, and of gaining floor joists into the sills as practiced in light framing. There is very little of the old-fashion mortice and tenon framing any more. Principally the timbers are just halved together and spiked into place. When floor joists are gained into sills and girders they are usually gained into the sills or girders so that the joists have a bearing of two or two and one-half inches on the sills or girders, and the depth of the gain is usually two inches less than the width of the joist it is to take, and this two inches is cut out of the joist on the lower edge to let it come flush with the sill. This may be seen at A in Fig. 103. It is often the case that girders can be set below the sills in the center of buildings and thus avoid the necessity of cutting gains in the girders. When this can be done it is better than to cut the gains, for it gives the full strength of the timber used.

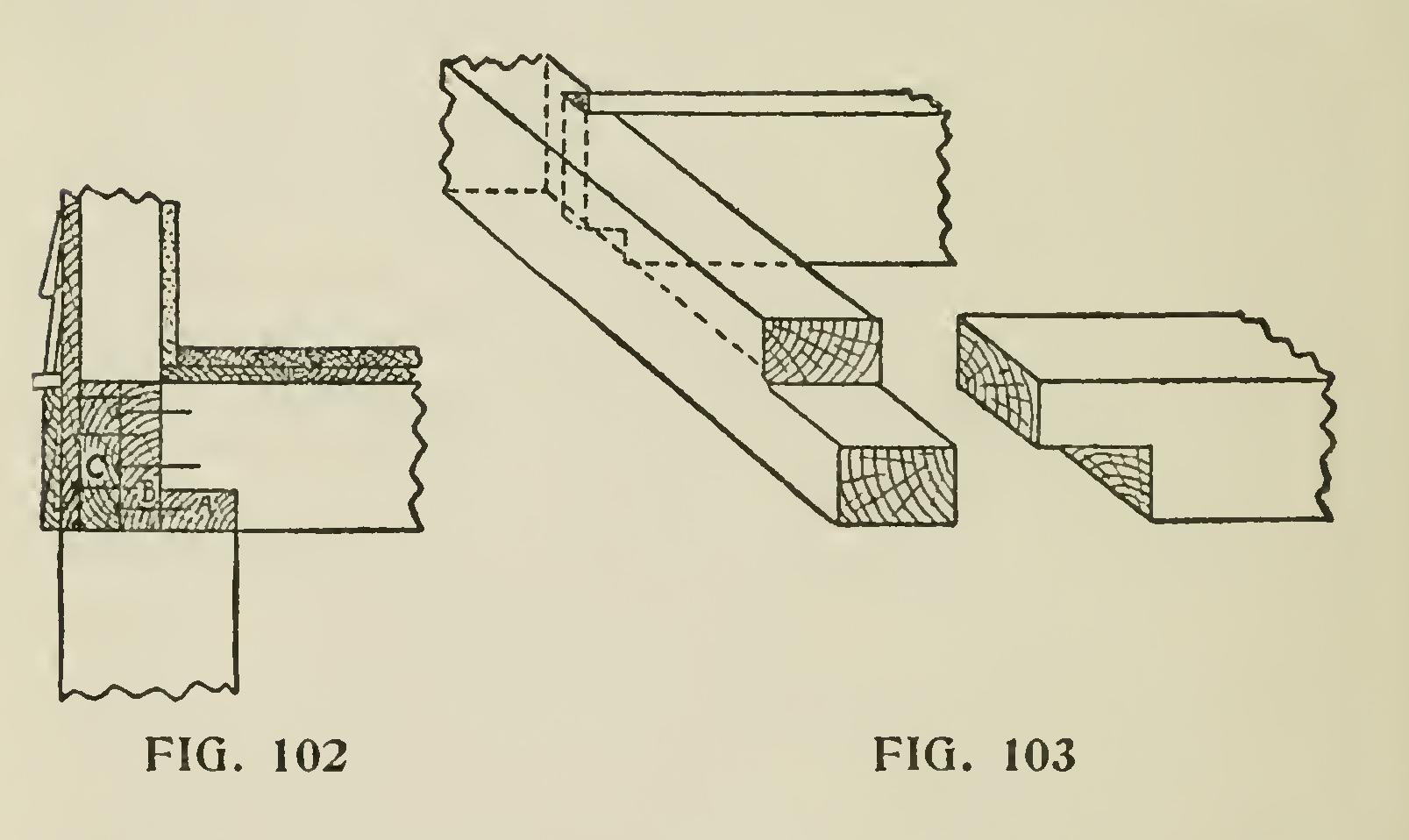

Making a Good Corner.

Fig. 104 shows a simple and inexpensive way of making a good corner for ordinary house framing. Take two 2 by 4's and spike them together, as shown at A and B, and on the inside corner spike on a 2 by 2 on each side to receive the lath. This will make a good solid corner for the lathing and has less lumber in it than the way some builders make corners, and is also better than the way some are constructed. The pieces C and D are only short blocks put in to make a nailing for the base in finishing. This is a matter that should never be overlooked in building a house. No mechanic can do a good job of putting down base unless there is something to nail it to. All the short blocks about a building can be utilized in a similar manner, as shown in the sketch, to make nailing places for base corners and by the sides of doors, etc.