Elements of House Framing

plate, fig, double, gutter, joists, frieze and rafters

Fig. 106 shows a better method. This method consists of putting a double plate around for the joists to rest on. The double plate makes a good bearing for the joists, one that will sustain any weight. By using the double plate it is much easier to keep the walls straight than with a ribbon board, which bends in and out at the slightest cause and is often hard to get straight, and harder ,still to keep straight. Then, again, the double plate serves as a first stop between stories. The double plate ought always to be used on the houses that are full two stories in height; it is far better than the ribbon board, and it will result in giving a straighter and better job all around.

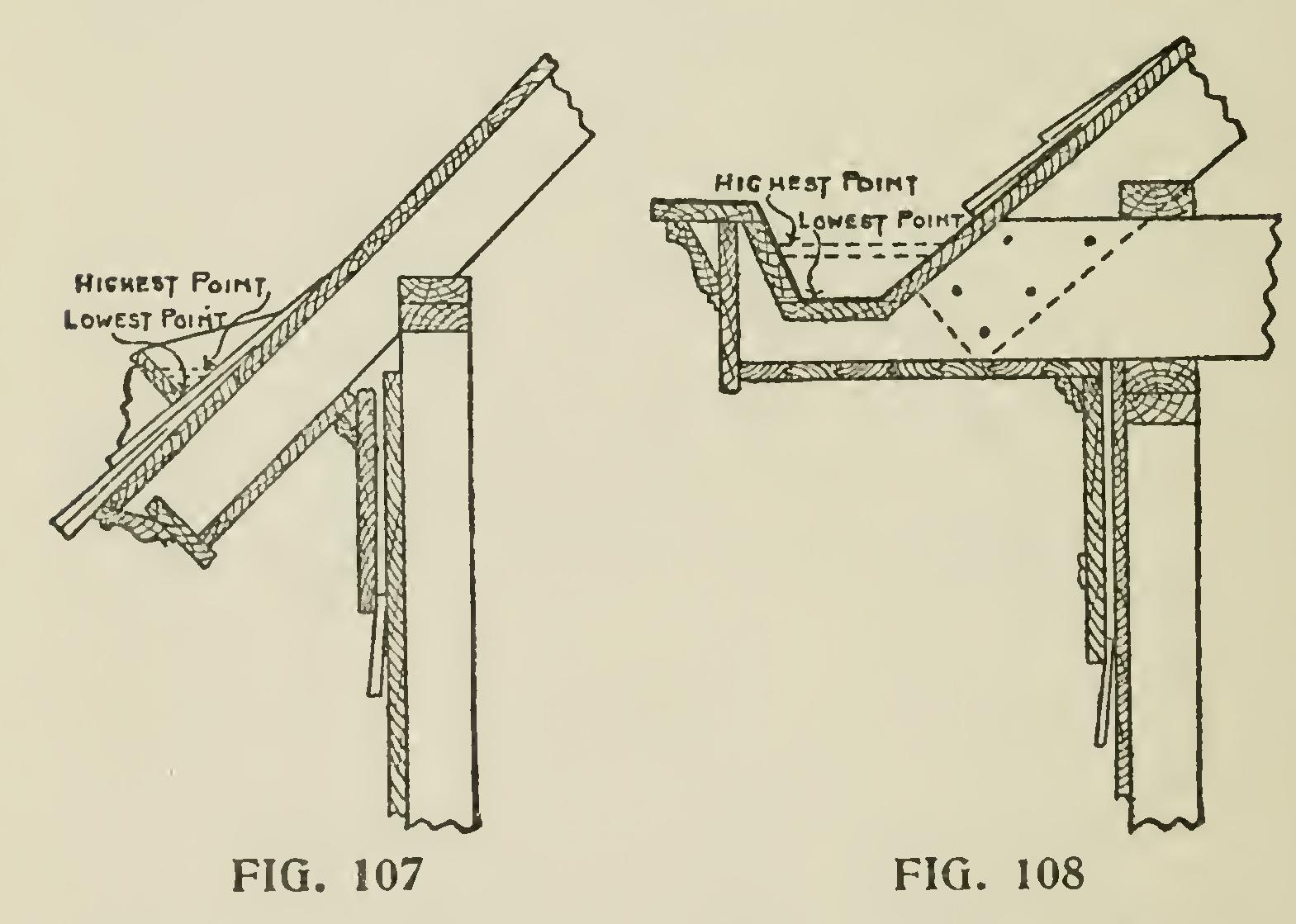

Fig. 107 shows a method of framing the foot of rafters for an ordinary square, plain cornice. On the average work there is probably more of this put on than any other kind. Double plates should always be used in order to bring the plate straight, even if it is not needed otherwise. This cornice provides for a frieze, plancier, fascia, crown and bed mold, as shown. The standing gutter shown on the roof should be placed either on the second or third course of shingle; the second course, unless for some cause it cannot be so placed. This gutter must be lined with tin, and the tin should extend up under the shingles at least five inches. The first course of shingles starting from the gutter must. be a double course, the same as starting from the bottom. The pitch in the gutter to run the water to the outlet is usually obtained by dropping the end, where the outlet is to be, down the roof a little. This is all right for short lengths, but for long runs it does not give sufficient fall to the gutters. When the fall or pitch is not enough it can be increased by putting tapering pieces in the bottom, as shown.

Fig. 108 . This is a large, square, box cornice, and is used quite extensively throughout the west, where a very wide cornice is desired, and particu larly on two-story residences. The plancier is made of flooring or beaded ceiling, and can be extended out to almost any width. Usually two to two and one-half feet is about the average. A double plate is used for the joists to rest upon, and the joists extend out to support the cornice and are cut out to form the gutter, cutting them deeper and deeper toward the outlet. Care

should be taken to cut them to a true grade, so as to thoroughly drain the gutter. This can be arrived at the easiest and most accurately by striking a chalk line on the ends of the joists (before the fascia is put on), from the high point to the low point. This will show the proper depth to cut each joist to have a perfect grade. Care should be taken not to let the line sag, in striking the line.

The single plate above the joists supporting the rafters can be varied a little if necessary. For example, if a narrower gutter is desired, the plate can be thrown out some, say four inches or about, but if this is done it should be remembered in cutting the rafters, for if thrown out it widens the run of the rafters, and would necessitate cut ting the rafters to meet the requirements in the case.

At A is shown a band mold broken around the frieze. This is usually placed about four and one-half inches above the frieze from the bottom of the mold, so that when window frames are set with the side casings up against the frieze, the part of the frieze below the mold forms the head casing for the frame and gives it a finished ap pearance.

Method of Setting Studding.—It is indeed a simple thing to set studding and yet it is surpris ing how many mechanics, and many of them good ones, set them apparently without any thought. This causes them a good deal of bother and work, as it results in the plaster cracking in the corners.

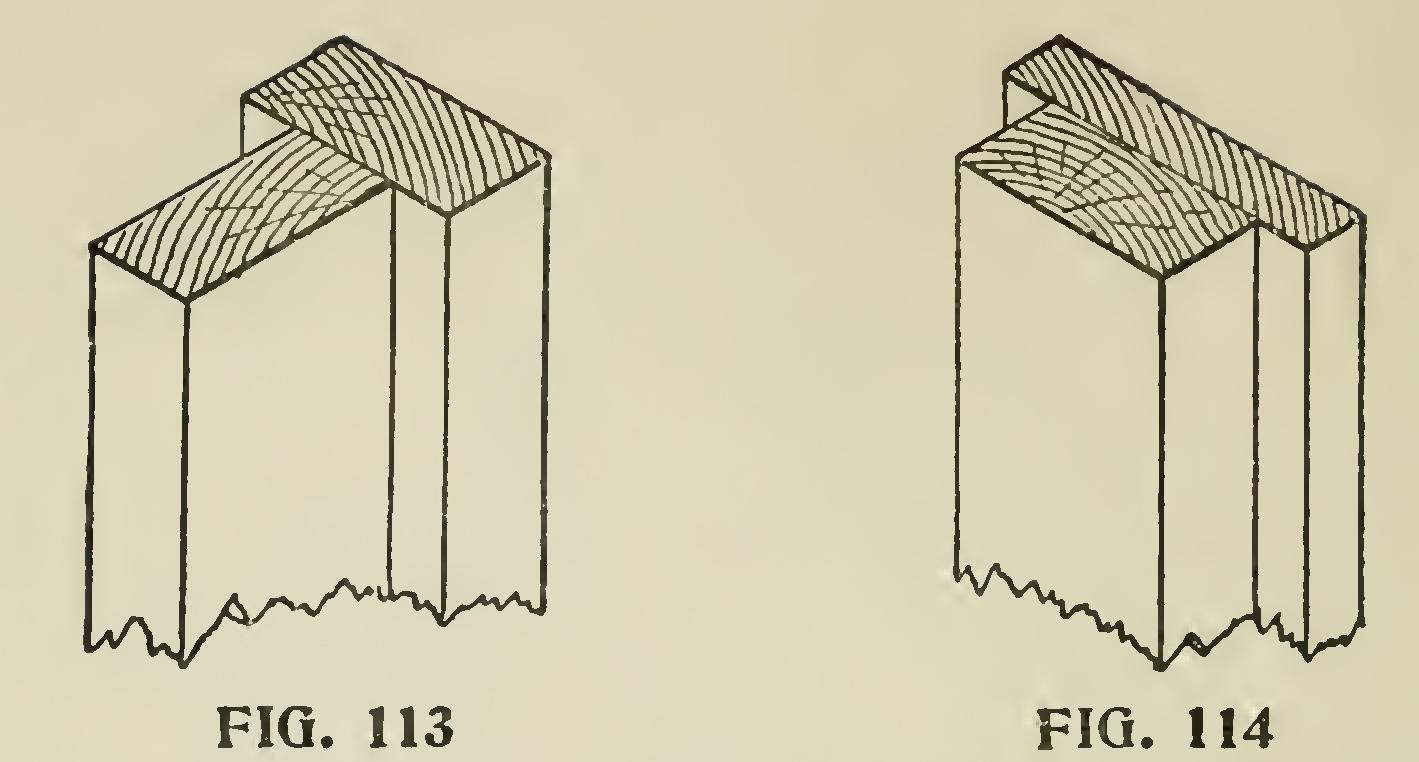

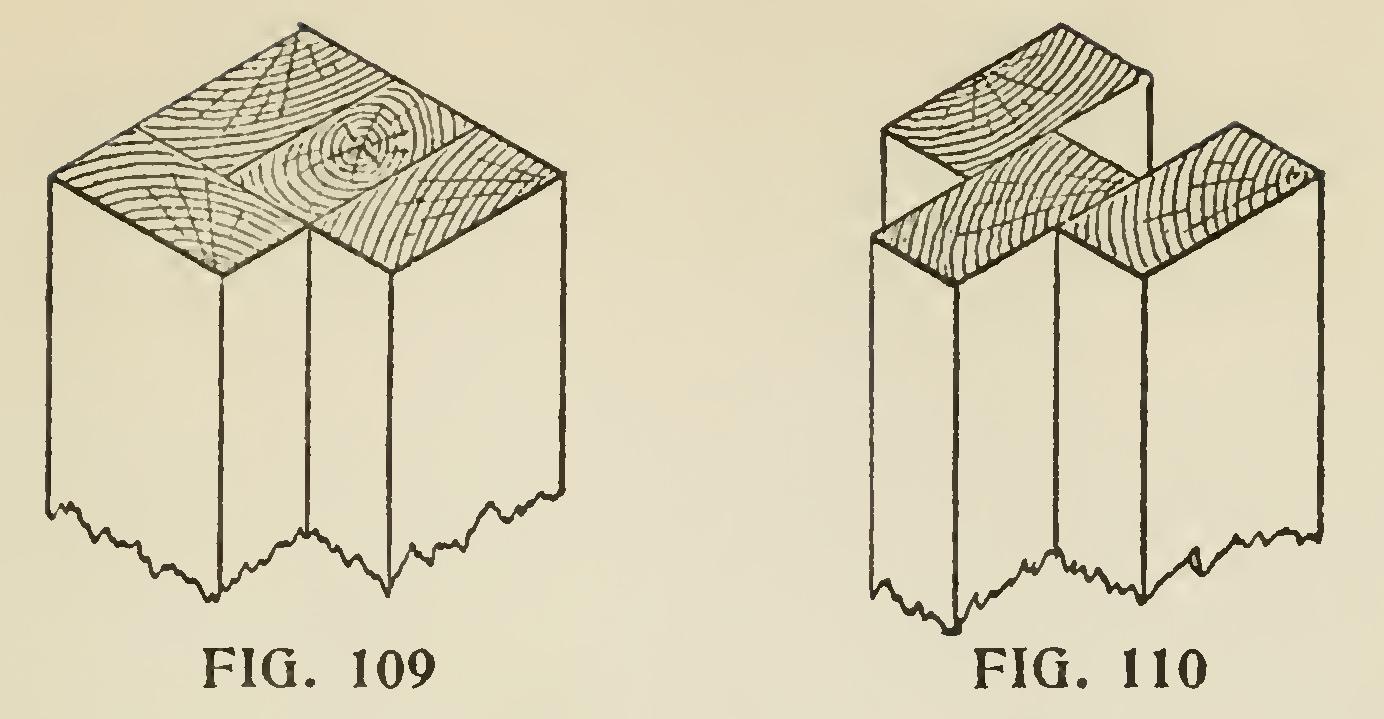

Fig. 109 shows a corner post made out of four studding, or the center one can be made out of short pieces—almost any carpenter knows how to make one—yet apparently few know how to make one practically as good, in less time and less lumber by nailing them together.

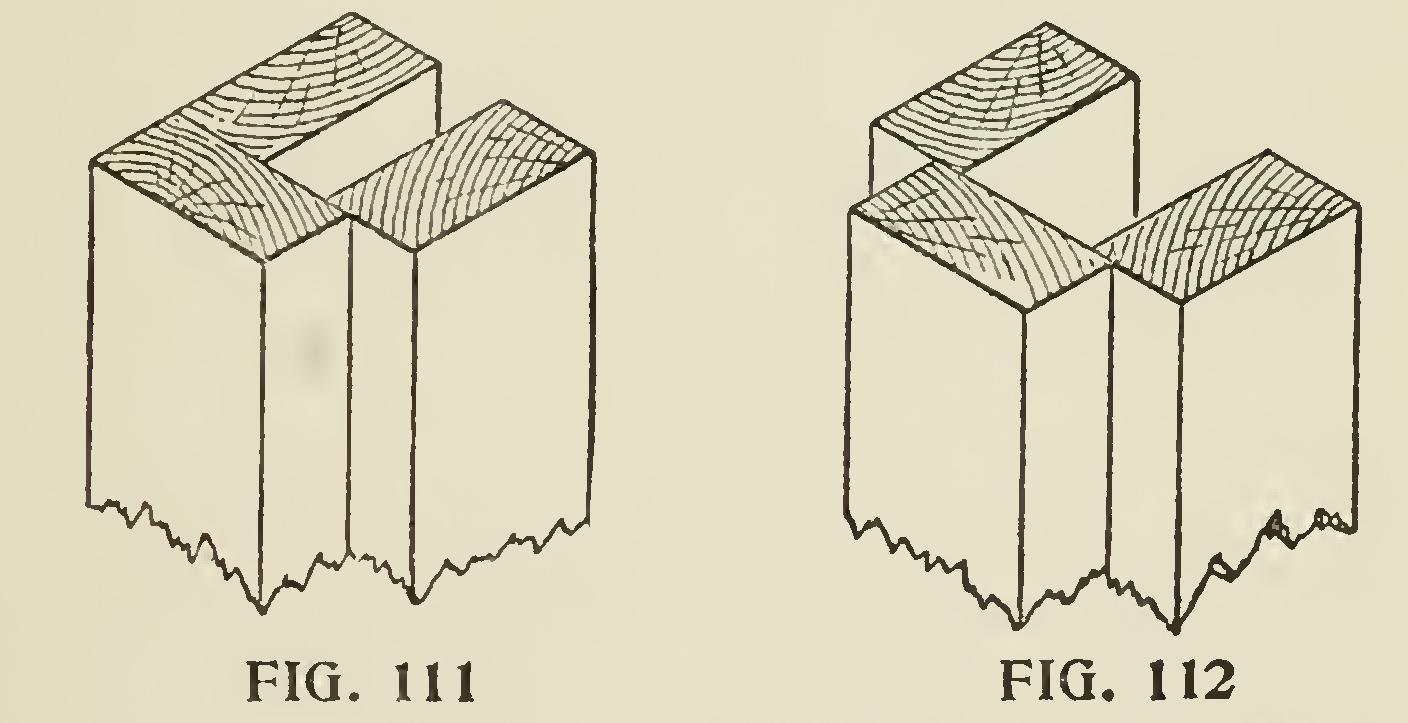

Fig. 110 shows an easy way and would be all right if the thickness of two was the exact width of one, but many times they are not, and so it is better to nail them together, as in Fig. 111. We have made them this way for years and we con sider them a very good corner.

Fig. 112 makes the best partition corner we know of. It is made much easier than one with blocks nailed in between two studding and then one nailed on the blocks, and my observation has been that it does not crack the plastering.

Fig. 113 is practically the same as Fig. 112. It is made for partitions which are made the flat way of the studding.